FRED DE SAM LAZARO, NewsHour correspondent: In the 1960s, two million people lived in Detroit. Less than 900,000 live here today. Homes, like factories, are shuttered. The last elected mayor is in jail. And the football team lost all its games last season.

In a city short on optimism, this woman is known as an apostle of hope.

ELEANOR JOSAITIS, co-founder, Focus: Hope: It doesn’t happen unless we all hang in there together and say, “We’re not going to be intimidated by this.” God bless you. Keep up the fight.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Eleanor Josaitis has brought reconciliation, even created an island of prosperity, in one of America’s most distressed and racially polarized cities. She’s equally at ease whether among childcare workers organizing for better pay or Detroit’s glitterati, like General Motors CEO Rick Wagoner.

RICK WAGONER, CEO, General Motors: She’s my hero.

ELEANOR JOSAITIS: Oh, listen to him.

RICK WAGONER: No, really. Thanks for everything you do, all right?

ELEANOR JOSAITIS: Love you, hon. Love you.

RICK WAGONER: Really appreciate it. Now, you take care of yourself and we’ll see you…

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: In 1968, she co-founded an organization called Focus: Hope, whose mission is to meet challenges with intelligent, practical actions, joining the late Father William Cunningham. They began working in Detroit to heal the growing racial divide in a riot-torn city. William Jones, a former Chrysler executive, recently became the group’s CEO.

WILLIAM JONES, CEO, Focus: Hope: Eleanor stands about five-foot-three and generally is the tallest person in the room. And I can say that. I’m six-foot-seven myself. But, generally, she’s the person that everybody sees. She’s also very, very compelling in terms of presenting the story of Focus: Hope.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: In the 1960s, when whites were leaving in droves for the suburbs, Josaitis did the opposite. She took her family, including five children, and moved from the suburbs into Detroit to help Father Cunningham. It was a controversial move that provoked a painful family rift.

ELEANOR JOSAITIS: Were there challenging times? Extremely challenging, like when my mother hired an attorney to take my five children away from me. But if I’d have kept that pain in my heart, I’d never had been able to accomplish what we’ve done.

Founder overcomes tough times

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Focus: Hope began by distributing winter clothes and surplus government food commodities, but then it took on a very different challenge. In 1970, it sued Michigan’s largest insurance company for race discrimination. The litigation lasted 13 year, which saw powerful early supporters pull away.

ELEANOR JOSAITIS: The foundations left us, the corporations, the trust funds. You see, you get a lot of hugs and kisses and “God bless yous” when you’re providing food to people. But when you’re challenging a society or an institution, it’s not considered proper.

We won $10 million for the people that were discriminated against, and we run — we have a trust fund that we will manage for 25 years.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Funders gradually returned, including, eventually, the insurance company they sued. The money it received allowed Focus: Hope to expand exponentially, serving all sectors of the community, from small children to hungry adults.

But perhaps its biggest focus was helping people get jobs. It targeted teenagers with special classes to boost their English and math skills. They were also taught discipline. Any drugs, even tardiness to class, meant immediate dismissal, Father Cunningham told us when we first started covering the organization in 1992.

FATHER WILLIAM CUNNINGHAM, Co-Founder, Focus: Hope: We’re not in the business of saving souls here. We’re in the business of providing serious performance capabilities to young black men and women and others.

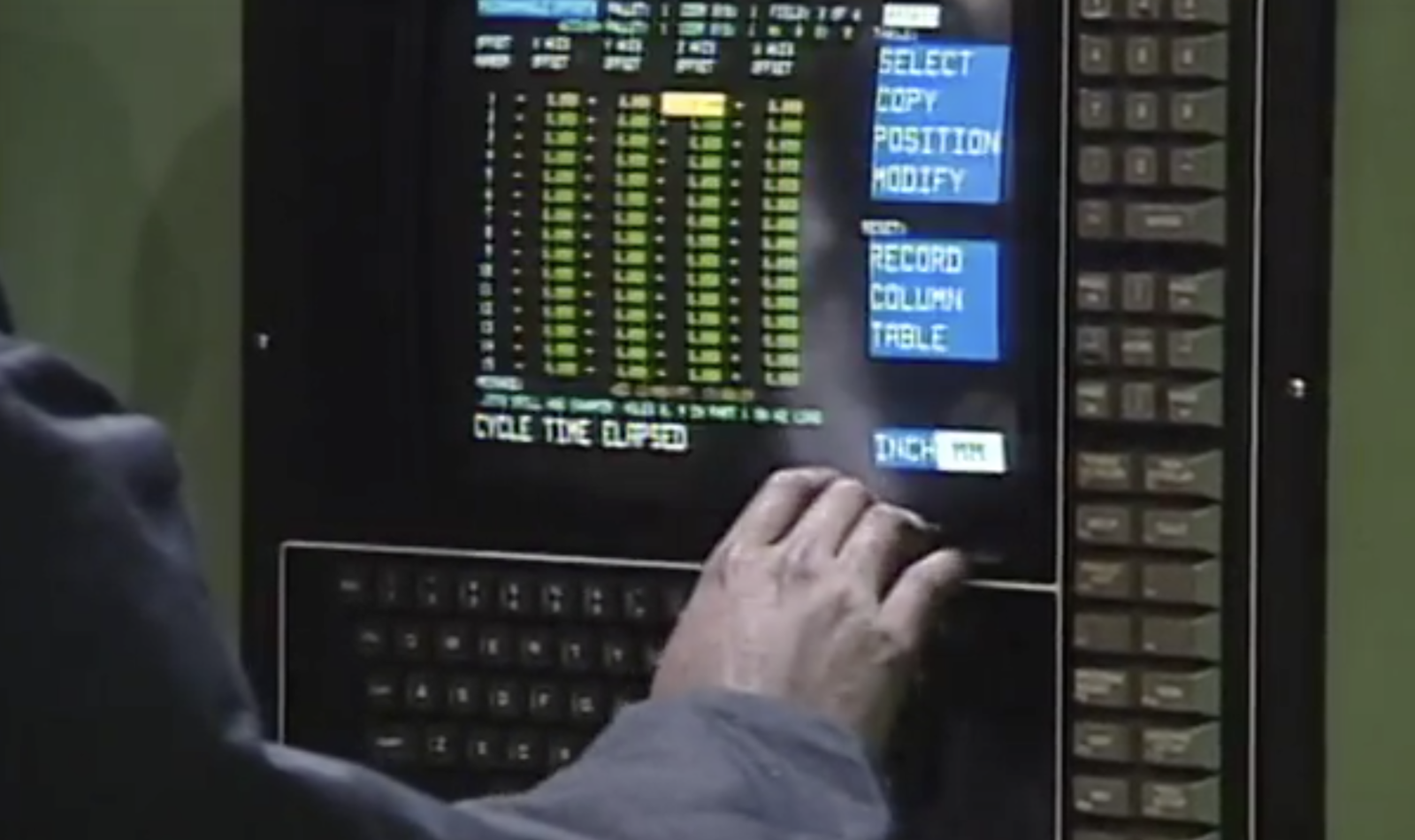

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Focus: Hope also provided vocational training, bringing together former autoworkers who’d retired to the suburbs with inner-city students. The kids, like Andre Reynolds, dreamed big dreams when we met him 16 years ago.

ANDRE REYNOLDS, former trainee, Focus: Hope: So, if they have a problem, let’s just say in Germany, or in Japan, they will say, “Well, who can we get to solve the problem?” They say, “Well, call Andre Reynolds.” “Where is he?” “Well, last I heard, he was in Washington.” So they call me up, and I fly down to Japan, and I won’t need a translator, because I already know the language myself.

Focus: Hope evolves its mission

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Focus: Hope dreamed big too, lobbying both industry and government for funds in the early ’90s to turn a shuttered Ford factory into a cutting-edge center for advanced technologies. Father Cunningham said it would have an impact way beyond those being trained within.

FATHER WILLIAM CUNNINGHAM: It’s good of you, Senator. Thank you. God bless you. The check’s for $20 million.

In the center of Detroit, where the little kids can walk down the street, look in the windows, and see their older brothers and sisters in the highest ranks of technology, what a marvelous thing that is to see.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Focus: Hope’s fortunes rose along with the car companies in the mid-’90s, becoming a parts supplier to the industry and plowing all profits back into its programs. However, with growing outsourcing and slumping fortunes at the big three, this grand teaching factory experiment mostly came to an end.

ELEANOR JOSAITIS: I’m going to use the word “painful,” because that is what’s painful to me, to see this go, because this was Father Cunningham’s dream and vision, and we were really cranking it out.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Today, Focus: Hope’s annual budget — around $25 million — is about a third of its peak a few years ago, mostly because it got out of the parts manufacturing business.

A lot of people will watch this and say, “You built this whole thing for an industry that pulled the rug out from under you.”

ELEANOR JOSAITIS: No, I mean, it’s just the time. I don’t blame the automotive industry. I mean, it’s changing times. And everybody’s got to change with it. And we’ve got to be in a transformational mood just like they are. And I just refuse to be intimidated by the moment. It’ll turn around, and we’re going to help turn it around.

And what are we doing with the contracts for the Navy?

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Despite the downturn, Focus: Hope is trying to stay ahead of the curve, turning from manufacturing to research. It has contracts with the Navy and is helping develop a so-called mobile parts hospital for the Army.

It’s like a MASH unit for vehicles, is that essentially it?

The slow economy aside, experts say there’s a severe shortage of machinists and engineers across the U.S. They say the prospects remain very bright for the 200 engineers and 2,400 machinists who’ve graduated from here.

TEACHER: And you can connect your Ethernet cables to the routers, but do not connect serial cables until you can figure that router.

Personal stories inspire co-founder

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: And for almost a decade, Focus: Hope has also trained almost 1,000 students in the growing information technology field.

ELEANOR JOSAITIS: You know, the thing that thrills me most is when the young people that we train around here come back and throw their arms around me and say, “I’ve got a job, I’ve bought a house, I got married.” I mean, you know, those are the things that keep me going every single day.

ANDRE REYNOLDS: Hello, Ms. Josaitis.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: One of those whose story thrills her is Andre Reynolds, the young dreamer. He went on to get his engineering degree and is now a seven-year veteran at Ford, part of the design team for new models. Reynolds says one of the most valuable lessons he learned at Focus: Hope was how to survive the bruising automotive downturn.

ANDRE REYNOLDS: You have to actually show the company that, hey, you’re hiring me because of these skills that I have. And not only do I have these skills, but I can also adapt and learn more skills. I learn different software, different techniques every day of my job.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: As for Eleanor Josaitis, 70-something and a cancer survivor, she keeps on going.

ELEANOR JOSAITIS: Thanks for the check. Yes, I know.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: She works 12 hours a day and has no plans to retire.

The world’s most modern factory

With Defense Department funding, a non-profit organization has built one of the world’s most modern factories in one of Detroit’s most blighted neighborhoods. Focus Hope, founded during the civil rights fight of the 1960’s, is providing more than high-tech training for inner-city residents; it is providing opportunity.