FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Many Buddhist temples are tourist attractions in Thailand. But this one, tucked away in a hillside north of Bangkok, is unusual. It was built a decade ago to be a hospice, a place where AIDS patients come to die with dignity. There are about 300 beds here, a fraction of the demand. But thousands of tourists, most of them Thai, come through each week. They meet and take pictures with AIDS patients; view the stark crematory and bone room, where the bones and ashes of patients lie in piles thousands high; and the after-death room, a macabre display that more befits a pathology museum. In fact, tourist donations sustain this facility, and the founding monk says it helps sensitize the public to the AIDS problem and educates school kids, who arrive by the busload.

PHRA ALONGKOT DIKKAPANYO: If they can see for themselves, not only listen or look at the pictures, they can understand easily. And it is a good way of education in our country.

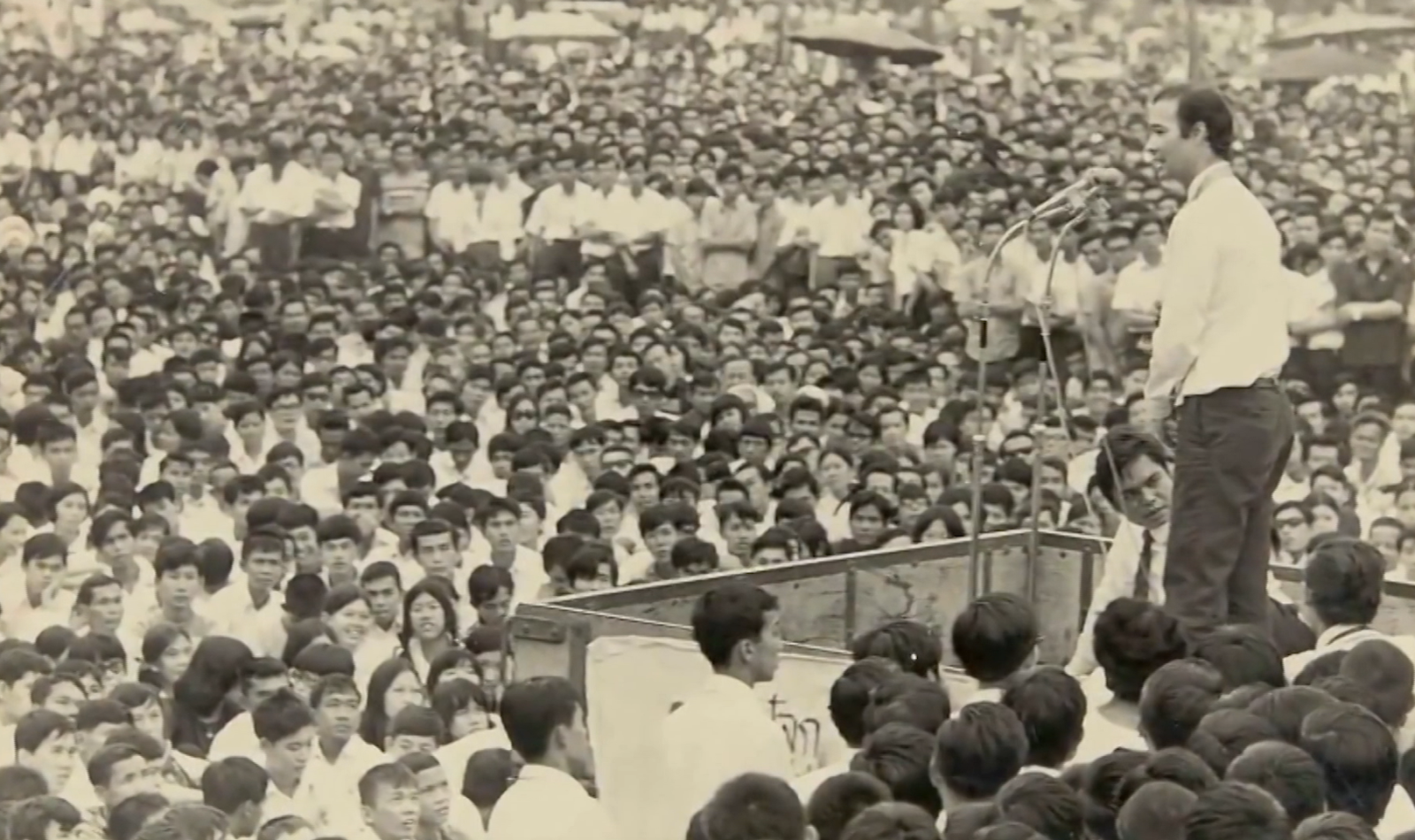

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Thailand has long been in the vanguard in tackling AIDS. It was the first Asian country to suffer an epidemic centered around another enduring tourist attraction: The commercial sex trade, which caters both to Thai and foreign tourists. Thailand had a quick response when AIDS hit in the early ’90s. Not with money or health services, but with its highly successful family-planning program. It had popularized one of the most effective weapons in AIDS prevention: The condom. The campaign was led by Mechai Viravaidya, a politician from a prominent family, economist by training, but best known as Thailand’s “Condom King.” We first interviewed him last year.

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA: We said, “Look, one must not be embarrassed by a condom. It’s just from a rubber tree, like a tennis ball. If you’re embarrassed by a condom, you must be more embarrassed by the tennis ball. There’s more rubber in it.” We said, “You could use it as a balloon, as a tourniquet for snake bites and deep cuts, you can use the lubrication for after-shave lotion, and use the ring of the condom as a hair band. What a wonderful product. Why be embarrassed by it?” So we gave them out all over, and said, “Look, the condom is clean in your mind, it is not dirty. So please, take one.”

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Viavaidya took his case early to monasteries and monks. Surveys shored they where the most influential people, especially in rural areas of this predominantly Buddhist nation of 60 million. Leading scholars were asked to develop a structural basis for the campaign.

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA: And in the Buddhist scriptures it said, “Many births cause suffering,” so Buddhism is not against family planning. And we even ended up with monks sprinkling holy water on pills and condoms for the sanctity of the family before shipments went out into the villages. So when AIDS came along, it’s like using “Gone With the Wind” in Technicolor and stereophonic sound. It’s just redoing the family planning program and getting out to the public.

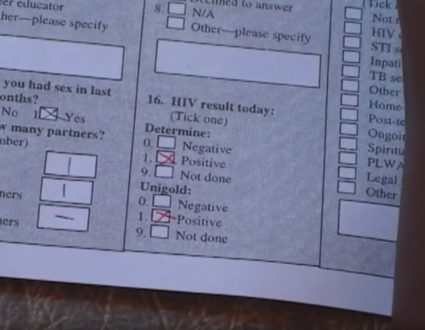

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The renewed condom and AIDS information campaign is widely credited with a dramatic drop in the number of HIV infections, from about 140,000 a year in 1990, to about 30,000 cases a year a decade later.

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA: So any customer who buys some fruit will also get condoms and AIDS safety tips.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Fewer Thai men visit brothels, and of those who do, the number using condoms went from below ten percent to more than 90 percent. But amid the severe Asian financial crisis, Thailand cut funds for its AIDS campaign in the late ’90s. That’s blamed for an increase in infections among certain key populations, including pregnant women. Experts say this group represents the emerging generation of adults, and the message hasn’t resonated with enough of them. Viravaidya says the lesson is: There is no room for complacency, and that campaigns must be sustained.

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA: You can’t just do it for a year and stop. You have to continue and change your message, put it into soap operas, commercial movies again; we have to redesign our public education program and make it a bit more jazzy compared to its last days of somewhat dullness.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: So, it just basically lost steam?

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA: Yes.

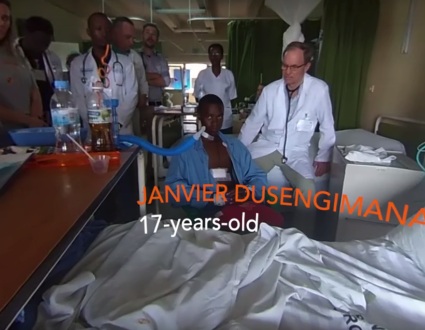

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Viravaidya is confident Thailand’s infection rate can be contained once again. Awareness is high, as is literacy, as is the availability of condoms. The big problem is how to deal with the one million or so Thais already infected. Tens of thousands of previously symptom-free HIV patients are now in the visible, advanced, or terminal, stages of the disease. The campaigns may have raised awareness, curiosity, and even generous donations, but patients like Phra Choochart, one of about a dozen monks here, say that doesn’t translate to sympathy or compassion.

PRA CHOOCHART: I keep secret for many years. But finally, something happened in my skin. It beginning to appear. I cannot keep secret anymore. So, I come to be a monk because in society if you catch HIV, nobody want you; also your family.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Family members rarely visit patients, most of whom are from the lower socioeconomic groups. The monastery offers a refuge. But with the pressing numbers, even here, the care seems more matter of fact than compassionate. Chris Lack is a recent medical graduate from Australia, one of several foreign volunteers.

CHRIS LACK, Volunteer Doctor: Right, so these are the coffins that every day when patients die and they’re loaded into one of these, and then the next morning they’re taken in a truck out here and off to the crematorium. There are seven, seven ovens in the crematorium. So, apparently, when they were building it, they built it with the belief that… that, you know… I might just go over and check if this guy’s alright. He’s still alive. He will probably die tonight. He’s held on for a couple days now, and he didn’t seem like he would, but he’s… pretty much all that moves now are his eyes, and even his eyes only sometimes move. So, he’s very much in the last stage.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Death here is a no-frills affair. Every day, an average of two to three patients die. They are transferred to the crematory, and after a brief Buddhist ceremony, the bones and ashes are piled up ever higher. Few patients remains are ever claimed by their families. The Abbott hopes in time that the hospice will teach people that AIDS needn’t be contagious; that families should care for their loved ones at home.

PRA ALONGKOT DIKKAPANYO: I try to give knowledge to our people for a long time, ten years. And nowadays, they can visit the patients. They like to learn, they like to visit, but they cannot touch the patients. Maybe five or ten years in the future, our hospital will be like a school: It gives knowledge; people can come here and learn how to look after the patient in their family.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Also, the Thailand government will soon make available at just a dollar a day the so-called cocktail drugs; these expensive anti-retroviral drugs are now commonly used by HIV patients in the West; in time, they should extend the lives of Thai HIV patients and lessen the need for spaces like these. Right now, this monastery has a waiting list of 10,000 AIDS patients.

A Waiting List

The Thailand government will soon make available at just a dollar a day the so-called cocktail drugs. These expensive anti-retroviral drugs are now commonly used by HIV patients in the West; in time, they should extend the lives of Thai HIV patients and lessen the need for spaces like these.