- JIM LEHRER:AIDS in the developing world. This week, thousands of delegates are meeting in Bangkok for the international AIDS conference. One of the main themes is the need to improve access and treatment. Fred de Sam Lazaro of Twin Cities Public Television has a look at another part of that problem, testing for AIDS. A version of this segment first aired on PBS’s Religion and Ethics.

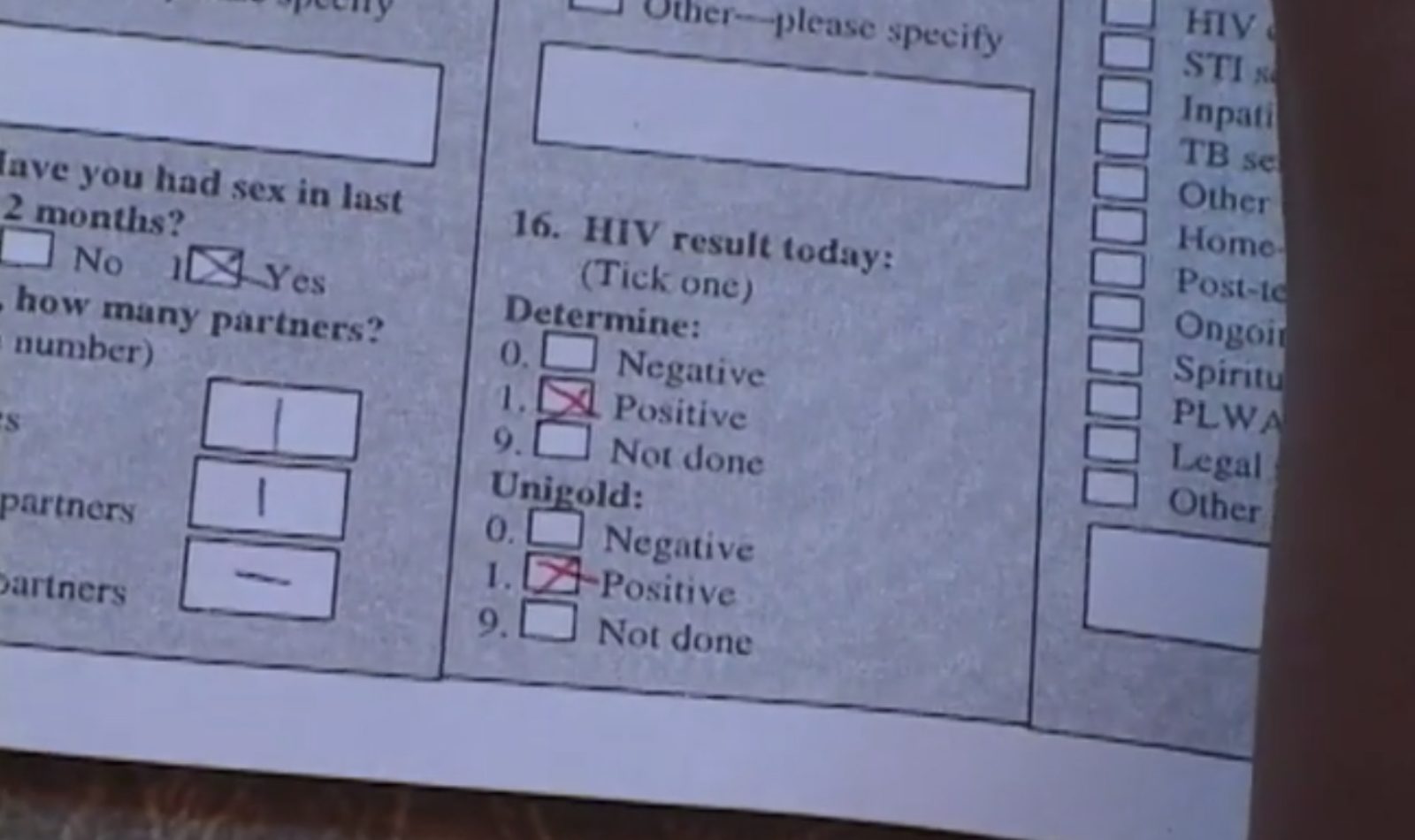

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:In much of the developing world, an AIDS test, if one is available, is a dreaded event. That’s because in poor countries where there’s no treatment, being HIV positive is tantamount to a death sentence. Here in southern Sudan, this 28- year-old woman came in after suffering skin rashes and fever.Sudan is just emerging from decades of civil war. Its poverty and displaced populations are a recipe for an outbreak of HIV, which currently affects an estimated 3 percent of the population. At one of the few clinics offering care, Counselor Grace Kadayi, with American Refugee Committee, a U.S-based agency, prevailed on her client to be tested: A tough decision, and in this case, a tough outcome. The woman was HIV positive.This client is a typical case, a woman infected by a spouse who had many other sex partners. He’s not part of her life anymore, she said, but he is part of perhaps the grimmest AIDS statistic: More than 90 percent of those who are positive don’t know it, and continue to infect others for years before they finally become ill. Former U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. Richard Holbrooke heads a business association that is calling for expanded testing. He says it’s the only way to stop the spread of AIDS.

- RICHARD HOLBROOKE:In no other health crisis in modern history would testing not have been a massive central factor. As a doctor said to me once, they threw out the whole rule book on epidemics when AIDS hit. And yet AIDS is the worst health crisis in history. That was because of the stigma. That was because of the battle over the way it spread.And as a result, a public health crisis was turned into a political issue, and testing became voluntary because they were afraid that confidentiality otherwise would be violated, and they would be stigmatized. But it should have always been encouraged testing– not mandatory, but encouraged testing.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:He says the early association of AIDS with gay men in the U.S. fed fears that patients would face stigma and discrimination, a fear well- founded in many conservative societies in the developing world. It’s one reason many activists are leery of moves that could coerce people into taking tests. Mechai Viravaidya has long led the AIDS prevention effort in Thailand.

- MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA:Anything, when it comes to matters between the navel and the knee, history of mankind has proven that force doesn’t work. There are ways where people have been coerced into doing it. I think we have to respect– have respect for the humans. And humans are humans, and we need to educate and convince them and get them to agree. That’s my only way that I think it’s going to work.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:He and others say voluntary testing can work, particularly now that antiretroviral, or ARV drugs are becoming affordable in more developing nations. These life-extending drugs have long been available in rich countries like the U.S.

- RICHARD HOLBROOKE:Isn’t it better to find out who is infected, and even more importantly perhaps, who isn’t infected? And anyway, if you don’t know who has the disease, how do you know who to treat?

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:That’s exactly the question Botswana began to ask two years ago. This southern African nation is politically stable and rich in natural resources, especially diamonds. But it has a staggering infection rate: Four of every ten adults is HIV positive. Funerals are the most common social event.Two years ago, Botswana began to offer ARV drugs to all who needed them. But it still had trouble coaxing people to come in for tests, so last October, the government introduced routine testing for everyone entering the health care system for any reason. President Festus Mogae says steps had to be taken to safeguard medical privacy before the policy was put in place.

- PRESIDENT FESTUS MOGAE:My concern was the possibility that it might be perceived as being a discriminatory practice. But in fact, routine testing in health facilities was precisely meant to make it look normal, to circumvent stigma. The hope is that when more people will have tested, people will begin to talk about it as a routine matter, and thereby the remaining ones, they’ll go for testing.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Today in Botswana, patients are urged to take the test, but they’re also told they can refuse. So far, doctors say, very few do. Dr. Ernest Darkoh heads Botswana’s antiretroviral drug program.

- DR. ERNES DARKOH, Director, Botswana Anti Retroviral Program:What we did was, we took away all the value judgments associated with testing, you know? If you go to hospital and come back and tell your partner, “look, I had a blood pressure test,” I mean, it doesn’t evoke any kind of, “why did you have to have a blood pressure test?” But if you had an HIV test, we can imagine… I mean, your partner will say, well, why did you feel, in the middle of our happy marriage, you had to go now and get an HIV test? — and all we’re saying is, by making it routine, we’ve given people an excuse to be tested, because you’ll say, well, everybody gets tested.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Dr. Banu Khan heads the government’s AIDS program.

- DR. BANU KHAN:What we found is that maybe there was more fear and anxiety by providers and policymakers than was actually there amongst the people who test. People are coming out in large numbers. They are saying, why have you waited so long?

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:For their part, patients like Anna Ditaro, who’s been on ARV drugs for a year, say HIV infection is no longer a death sentence. And she says as priests and political leaders set the example by taking the test, AIDS is beginning to carry far less stigma.

- ANNA DITARO:I know a lot of people who have got higher positions who have tested, who are not positive and who are positive. They are like some priests in the churches, some counselors, some chiefs. They really encourage people to do it, and it’s a good thing to do.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:That political and religious leadership is considered critical in campaigns to reduce the stigma of AIDS. President Mogae, who used to say his country faced extinction from AIDS, now says Botswana may be turning the corner. Mogae himself took an AIDS test. It was negative.

- PRESIDENT FESTUS MOGAE:The fact that more people are… people are testing and many of them are proving negative, it’s going to be easier to encourage them to stay negative. The fact that we’re able to prevent mother-to-child transmission, these expectant mothers or new mothers, and even other parents with small children, who may be positive and whose children are not positive, they are… they are living longer. They are going to live longer.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Experts say Botswana will be closely watched as the first developing country that is trying to give its AIDS patients not only the right of confidentiality, but the right of access to AIDS drugs.

- JIM LEHRER:Extended coverage of the AIDS conference and interviews with experts can be found on our Web site at pbs.org.

Routine testing

Developing nations are closely monitoring efforts in Botswana, the first African country to both routinely offer confidential HIV testing and provide AIDS drugs to all who need them.