JUDY WOODRUFF: More than five months after floods swamped Pakistan, the process of recovery is barely beginning.

We have a report from Sindh Province by special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Vast swathes of Pakistan’s southern Sindh Province remain inundated, in some places under 10 feet of water. By official estimates, half-a-million of families are still in tent camps. An occasional farmer can be seen sewing the land, but the land is nowhere near ready to grow food, says the government’s top adviser on water and agriculture issues.

KAMAL MAJIDULLA, special assistant to Pakistani prime minister: The ability of the land to soak up that water is not there anymore. It’s not a sponge anymore. The sponge is loaded, and on top of which we’re in the winter season, so our evaporation rates have gone down.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Kamal Majidulla says its just one of the challenges that will slow the recovery from floods that blanketed almost all corners of Pakistan. A lack of international aid is another, which he blames on what he calls Pakistan’s distorted image as a refuge for terrorists.

KAMAL MAJIDULLA: We needed $10 billion to start with. The effect of the damage is something within the region of $50 billion. We haven’t even got close to $10 billion. And I think that a fair bit of that has to do with the kind of coverage Pakistan gets around the world, which is, sadly, quite untrue, because you can’t sort of take specific little areas where a conflagration is taking place — and it’s a serious conflagration, and it needs to be eradicated, no question about it. But there are 180 other million people living here.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Ironically, even within Pakistan, there’s an image problem that’s slowed aid to the regions associated with militancy and conflict. We traveled to the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, along the Afghan border, thought to be a haven for Taliban militants, who’ve been targets of the Pakistani military and U.S. drones. Like most of the northern areas of the flood zone, the waters have receded here. But much of the farmland is still smothered under up to five feet of silt. These farmers say people are down to selling what little assets they have, like livestock that survived the floods.

MAN (through translator): Initially, some groups did come with rations and food, but, after a while, they disappeared. One of the reasons is, the location of this area is tribal-troubled, so people are not very willing to come and work in these parts.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Although extremists do live in this area, local aid worker Maqsood Alam says they have caused no trouble after the flood.

MAQSOOD ALAM, relief worker: I have been working in this district for the last four months, but I have not seen any kind of trouble with any organization.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: But people in normal sort of aid agencies are very reluctant to come here because of the history of militancy; is that true?

MAQSOOD ALAM: Yes. Strategically — I mean, strategically, it is placed at such a junction of these tribal agencies, that nobody dares to come to this part. That is — you are right, I think.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Alam works for a quasi-government agency, one of few aid groups working here. With a grant from the New York-based Open Society Institute, they’ve begun to restore the farmland and also irrigation canals, which were washed away.

Ninety-five percent of the families here are without their only source of income, he says, and it will be a while before they will harvest a crop.

How many people are you talking about totally, how many families?

MAQSOOD ALAM: Probably 500 in this area alone. In the surrounding area put together, probably, it comes to more than half-a-million.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Half-a-million families?

MAQSOOD ALAM: Families that have subsistence kind of (INAUDIBLE). They have lost their source of income generation.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Outside of the main areas of conflict in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, life is marginally better.

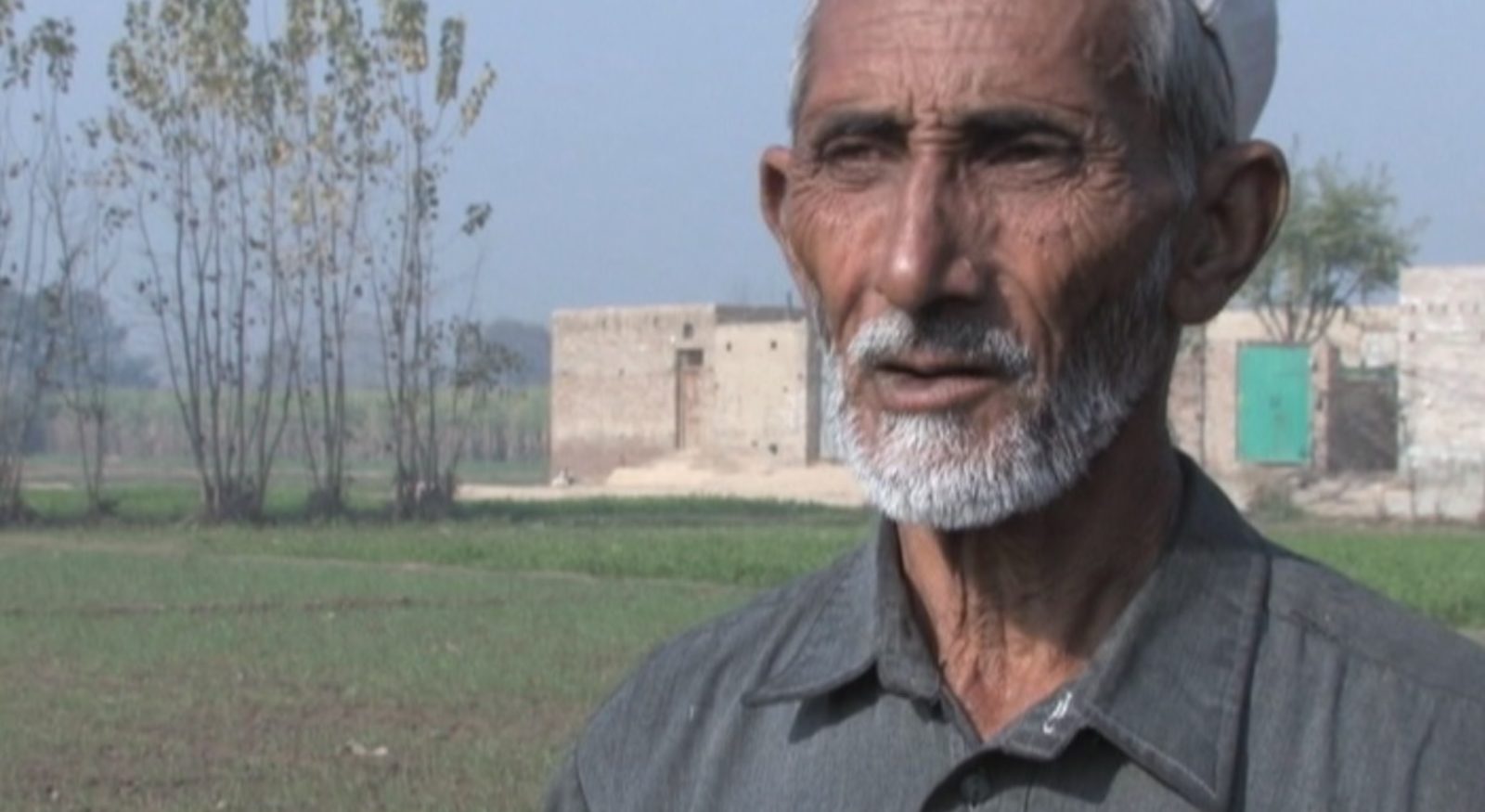

Kala Khan is a bit farther ahead in rebuilding his livelihood — a bit. He received a $220 grant from the government, along with some seeds and fertilizer from a private Pakistani aid group to replant the 1.5 acres he rents to grow wheat and this fast-growing animal fodder.

But he also borrowed about $2,000, twice this family’s annual income, from neighbors and relatives to help rebuild the simple dwelling that houses an extended family of 10. It’s far from done.

KALA KHAN, farmer (through translator): This is where my wife and I used to sleep. It was completely destroyed.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: For now, his wife shares a finished room with their two daughters. Next door, he shares this space with the family’s prized possession: a water buffalo.

KALA KHAN (through translator): My biggest burden is to pay back that loan. Our biggest expense is food and rations. It would be easier if we got more rations. We have to decide how much to spend on living, how much to pay back. After all, my stomach is important, my children’s stomach is important. It will take some time.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Spartan as life seems, Khan says he’s better off than many others.

KALA KHAN (through translator): I saw on TV that, some places, the floods were so drastic, not only did people’s crops and homes get washed away, but also their children. So, I’m thankful to God for sparing our lives. Our buffalo were safe. OK, our crops will come back, but there are people who’ve lost a lot more.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: For these worst-affected flood victims, most in the downstream Sindh Province, life will likely remain on hold for several months, even years.

Simi Kamal is a water policy expert and activist.

SIMI KAMAL, water activist: I think problems that are — that we have to deal with are basically over the next year or two, really to help these people get back on the land, help them stay away from diseases as much as they can, help them with their own food needs, help gets the kids to school, you know, help them get over this winter.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: And, ironically, amid all this flooding, Kamal says Pakistan actually faces a water shortage over the long term, thanks to inefficient use of groundwater on its farmland and the prospect of disappearing Himalayan glaciers that feed this country’s rivers.

At stake is not just the freshwater supply, she says, but the very food security of this large, complex nation.

JIM LEHRER: Fred’s report was a partnership with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and the Under-Told Stories Project at Saint Mary’s University in Minnesota.

Washed Away

Five months after floodwaters washed away homes and villages in Pakistan, some parts of the country are still underwater. Fred de Sam Lazaro reports on the slow process of recovery from Sindh Province.

“We have to decide how much to spend on living, how much to pay back.”

Kala Khan