RAY SUAREZ: Finally tonight: a rare look inside Syria, an Arab country where the street protests are just beginning.

We have a report from special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro, one of the few American journalists admitted into Syria recently.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The people of Syria’s crowded capital, Damascus, face many of the same ills that have triggered street protests in so many other cities in the Arab world. There’s high unemployment here, widespread corruption and authoritarian one-party rule.

Yet, unlike Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak or Libya’s Moammar Gadhafi, Syria’s Bashar al-Assad has faced minor and scattered demonstrations. But the situation is fluid and possibly escalating. Scenes from YouTube claim to show protests across the country, including Daraa, where there were deadly clashes.

Assad, who took power 11 years ago after the death of his father, has taken recent steps to put more money into people’s pockets, and pledged to loosen some of the tight restrictions that have marked his government’s rule. Subsidies on several food staples were increased, something well-received by this shopper in a Damascus market.

WOMAN (through translator): Everything is cheap. Cooking oil, rice, sugar, they’re all cheap this time of year.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: She praises the government of the 45-year-old Assad. An ophthalmologist trained in Britain, he promised to modernize a centralized, Soviet-style economy. Consumer and luxury goods were allowed in, and Syrians living abroad were invited to return.

Dr. Bouthaina Shaaban is a key presidential adviser.

DR. BOUTHAINA SHAABAN, Syrian presidential adviser: President Bashar Assad did many important steps internally. And more important than what he did is that he is responsive, and the government is responsive to people.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Syria has also taken steps to reform media regulations, including access to the Internet and social media.

In recent days, the government has removed a ban on several popular social websites, like Facebook and YouTube. Many people would get around the restrictions in the past, but now they have direct access. The key unanswered question is whether this is a political opening up, or a clampdown which allows the government to more closely monitor the use of these websites.

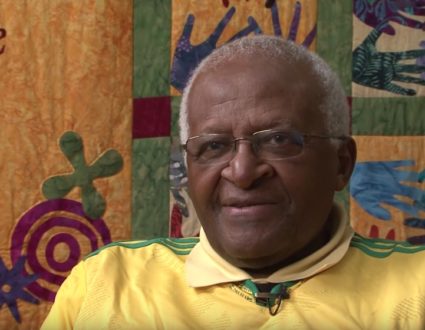

Veteran journalist Yahya Alous is skeptical about the changes governing media. He founded an online magazine on women’s issues in 2005. It has been forthright in tackling controversial social issues.

WOMAN (through translator): I’m working on the issue of sexual harassment that women face these days.

YAHYA ALOUS, editor (through translator): Covered women are also subjected to harassment.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Alous says the government mostly turned a blind eye to their work. But a new rule took effect a week ago requiring all such sites to be officially registered.

YAHYA ALOUS (through translator): The claim is that it will organize the Internet and protect the rights of individuals from slander and cyber-bullying, and prevent false data being published. But the truth is this is an attempt to control it. This law could result in the imprisonment of some journalists. And that’s a serious challenge.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Alous speaks from experience. He spent two years in prison earlier this decade for writing that angered the government. Since then, he acknowledges journalists have been given more freedoms.

YAHYA ALOUS (through translator): Five or six years ago, we were not able to discuss issues like honor killings or domestic violence in depth. Six years ago, we were not able to discuss corruption or senior government officials.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Are you concerned about talking to us today, as a foreign media crew?

YAHYA ALOUS (through translator): I think I would be lying if I were to tell you that I have no concerns talking to you. But the important thing to point out is that I’m not crossing any red lines, because I’m aware of where the red lines are and where they aren’t. Even government authorities openly discuss the issues that I’m talking to you about and sometimes much louder than this.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The U.S. ambassador here doesn’t think the changes go far enough. He says Syrians share the same aspirations as Egyptians, Tunisians or Libyans.

ROBERT FORD, U.S. ambassador to Syria: They want to be treated in a dignified manner, in an appropriate manner by their government. That includes everything from no mistreatment in prisons or in police stations, no torture, to the demand for political opening, the demand for economic opportunity. Those are the things which are driving the region. And Syria, I do not think, is immune from that.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Robert Ford took his position in January, the first U.S. ambassador here in six years. He says his appointment was an effort to take a chill out of U.S.-Syria relations. In 2005, the Bush administration moved to isolate Syria for its close ties to Iran and militant groups allied with it. That policy has not changed.

ROBERT FORD: We have a very tough sanctions regime in place preventing American companies from doing almost any business in Syria. We do this as a means of helping convince the Syrians that it is in their interests to stop supporting terrorist groups like Hezbollah and like Palestinian Hamas.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: That resistance to U.S. pressure may well have strengthened the Assad government, says Talal El Atrache, a journalist and author.

TALAL EL ATRACHE, author and journalist: Let me tell you something: The United States helped a lot to boost the image of the regime and its president because of its wars in Afghanistan, then in Iraq, then its unlimited support to Israel.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: He says Syrians strongly support Hamas and Hezbollah, both viewed as resistance forces against Israel, which occupied, then annexed the Golan Heights, captured from Syria during the 1967 war. Add to that, Atrache says, a deeply unpopular Iraq war and U.S. sanctions brought Assad support his departed counterparts in Egypt or Tunisia did not share.

TALAL EL ATRACHE: The difference with the other Arab regimes is that the credits that Bashar al-Assad got during the last six to seven years are going to give him more time to implement the reforms.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Many analysts worry about a growing gap between rich and poor. Unemployment is officially around 8 percent, but it’s likely much higher and hard to measure since many Syrians work in the informal economy. Add to them waves of new entrants to the labor market — 250,000 every year and growing in this country of 22 million.

For their part, government officials say they’re committed to addressing the challenges and complaints.

DR. BOUTHAINA SHAABAN: The people in the street are, you know, voicing their ideas. I mean, all the issues are at the table. We are not defending anything that is wrong or anything that is unsustainable. And everything is open to question.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Back in the Damascus market, one thing became clear: People don’t talk openly with foreign journalists, who aren’t commonly allowed in the country.

We were accompanied by a government minder for all outdoor shooting, although we were free to choose anyone to interview.

Does he sympathize with the fruit-seller in Tunisia?

We tried to ask this 18-year-old fruit vendor about the unrest in other Arab countries, but his father quickly intervened.

MAN (through translator): That’s not our job. Our job is selling fruit and vegetables.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Most of the analysts we spoke to until this week said they did not expect Syria to erupt in street protests, but they were quick to add that events are unfolding in ways no one can predict.

RAY SUAREZ: Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at Saint Mary’s University in Minnesota.

Teetering on the Edge

Fred de Sam Lazaro reports on the view of Arab world unrest from Syria, a country that until recently remained silent in the wave of uprisings challenging governments and demanding reforms across the Middle East and North Africa.

Unemployment is likely much higher than the official rate since many Syrians work in the informal economy, making it harder to measure.

Add to them waves of new entrants to the labor market — 250,000 every year and growing in this country of 22 million.

Yahya Alous spent two years in prison earlier this decade for writing that angered the government.

Since then, he acknowledges journalists have been given more freedoms.

“Five or six years ago, we were not able to discuss issues like honor killings or domestic violence in depth. Six years ago, we were not able to discuss corruption or senior government officials.”

Our team tried to ask this 18-year-old fruit vendor about the unrest in other Arab countries, but his father quickly intervened.