FRED DE SAM LAZARO, correspondent: In recent years, thousands of rural communities in Senegal have held extraordinary public rallies they call “declarations.” And they’ve declared an end to a deeply rooted practice, one rarely discussed in public and commonly known as female circumcision.

MOLLY MELCHING: Never in my wildest dreams could I have imagined that I would be sitting here years later, saying that 4,792 communities in Senegal had abandoned. In the beginning it was just unthought of, unbelievable, because it was so taboo.

DE SAM LAZARO: Molly Melching founded a group called Tostan-“breakthrough” in the local Wolof language-in the early ’90s. She had modest goals: to educate people about health and human rights, especially in rural areas and in local languages. The Illinois native is fluent in the ways of Senegal but she keeps a low profile in the work of Tostan.

Tostan’s work often begins with an ice-breaker, like an old movie. Many in the audience have never watched a film. To overcome the language barrier, the selection is a Buster Keaton silent movie classic from 1923, and it’s a hit. A more serious film followed, on vegetable gardening. It’s all part of seminars on nutrition, health, basic human rights, and other issues-in groups, songs, dances and drama.

Skit: She needs to be cut. All girls need that.

DE SAM LAZARO: It’s proven to be one of the most promising attempts in history to wipe out what Melching calls female genital cutting, a practice that dates back 2000 years. Each year, the World Health Organization says, up to 3 million girls in Africa are subjected to genital mutilation, and up to 140 million women live with its consequences.

Skit: You can’t have a recognized marriage if she is not cut.

DE SAM LAZARO: That cut is a painful rite of passage for girls across a wide swath of predominantly Islamic African and Middle Eastern countries. However, the practice goes back hundreds of years before Islam or Christianity and is also practiced in both faiths and religions native to this region. It’s thought to have originated in the harems of ancient rulers as a means of controlling women’s fidelity, or as a sign of chastity among those who aspired to be consorts.

MELCHING: Those who were in the rest of society could move up, and you could marry someone who was more prestigious or had more money, more status if you underwent this practice, because it was a sign of good reputation, And as the years went on, I mean 2,200 years, it became very much a part of what was considered criteria for good marriage.

DE SAM LAZARO: Melching came to this West African nation as a student in the 1970s and later as a Peace Corps volunteer. She stayed on to work on improving health education, which she found sorely lacking.

MELCHING: When you see a friend that you’ve known for several months and you’ve gone to her house for lunch, and then she tells you her child has some problem, that it’s someone who has cast an evil spell on the child, the baby, and that she’s going to take them to a religious leader to get the spell taken off, and you don’t know what to say. It turns out the baby was dehydrated.

DE SAM LAZARO: But from the health education, women began to understand infection, and Melching says they began to connect the dots.

MELCHING: So, suddenly as they started learning germ transmission and the consequences of FGC and how these infections occur and why they had more problems in childbirth than other women who had not been cut, they started saying wait a minute.

Seminar: People used to be afraid to talk about this before. Not anymore.

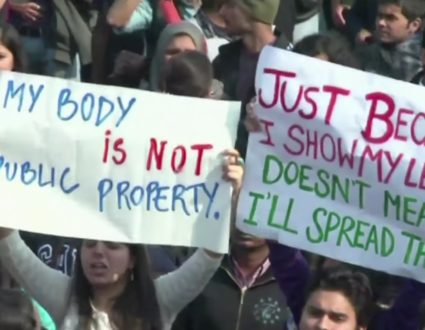

DE SAM LAZARO: But how did women in conservative, patriarchal societies become able to speak out, especially on a sensitive sexual topic? Melching says it’s because Tostan involves men and religious leaders who’ve confirmed that cutting is not required.

MELCHING: We share our modules with the religious leaders so that they see that everything we do is for the well-being of the community, the health, and all these things are things that Islam espouses, and so they’re very happy in general, but first of all they’re happy because we start with them. We respect them.

DE SAM LAZARO: And that respect also carries over in the group’s message on genital cutting.

MELCHING: Tostan found that using approaches that shame or blame people really was just the opposite of what would work in changing social norms. When you say to someone, we know you love your daughter, and you’re doing things because you love your daughter, but let’s look at this and let’s try to understand together exactly what are the consequences of this practice? But you are the ones who will have to make the decision, then suddenly people are willing to listen. They don’t get defensive.

DE SAM LAZARO: It’s far more effective than the approach of many aid groups-religious, government, and private, says Princeton University professor Gerry Mackie.

PROFESSOR GERRY MACKIE: Not hectoring and preaching but having pro and con discussions. When we think of an ideal way of making a change, we’d say it’s democratic. We all get together and talk it over and decide, what is the best thing to do? Whereas some development approaches would, say, force them to do it, pay them to do it, trick them into doing it.

DE SAM LAZARO: Tostan’s volunteers and staff who conduct its seminars all hail from the local communities. Often they are leaders and elders speaking from personal experience or anecdotes. Diarre Ba used to make a living as a female circumciser.

DIARRE BA: I was part of this process. I felt bad. This is not right. But I didn’t know anything at the time. I had no learning.

DE SAM LAZARO: Others have painful, vivid memories. Ibrahim Sankare was very close to an older sister growing up. He walked into her room one evening…

IBRAHIM SANKARE: I saw her lying in a pool of blood. I thought someone had really hurt her. I screamed. My father explained to me. Since then, even now I get goosebumps thinking about it.

MARIAM BAMBA: It was very painful. I will never-you ask me if I can forget it? I can never forget the pain. So painful.

DE SAM LAZARO: Marieme Bamba is a long-time campaigner against genital cutting, and she’s spared her 10-year-old daughter the trauma. Yet before she became involved with Tostan and early in her marriage, she was determined to keep up the tradition. Even her own husband was opposed to genital cutting.

SULEYMAN TRAORE: She insisted that she had to do it. There were so many problems if you didn’t do it. If you cooked meals, no one would eat your food. It’s because we didn’t know. People told us that it was our religion. If you don’t do it, you’ll be going against your religion. All this is false. But I alone can’t do this in the village.

DE SAM LAZARO: They say Tostan was able to insure they were not alone-that communities in which they intermarried were also thinking alike, that their daughters would still be marriageable. The large declaration ceremonies have been critical.

MACKIE: One part of bringing about a change like this is to get everyone to change at once, what we call “coordinated abandonment.” Everyone has to see that everyone else sees that everyone is changing.

DE SAM LAZARO: Genital cutting is not the only tradition they want to change. Many communities have vowed to end the frequent practice of allowing older men to marry adolescent girls, acknowledging both the health risks and the girls’ human rights. Molly Melching says there’s plenty of historical precedent for abrupt changes in social norms and attitudes. She sees a very current example every time she comes home-that’s in American views about smoking.

MELCHING: People were smoking, and nobody said anything about it much through the ’50s, the ’60s, and even the ’70s. As people became more and more aware of the harm that it causes, more and more people-there was a critical mass of people who started really protesting. It was amazing for me, coming from Senegal to the United States to see how quickly things turned around.

DE SAM LAZARO: Tostan’s efforts have now expanded to 14 other African nations.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Kaolack, Senegal.

Putting an end to female circumcision

The cut is a painful rite of passage for girls across a wide swath of predominantly Islamic African and Middle Eastern countries. However, the practice goes back hundreds of years before Islam or Christianity and is also practiced in both faiths and religions native to this region. It’s thought to have originated in the harems of ancient rulers as a means of controlling women’s fidelity, or as a sign of chastity among those who aspired to be consorts.

Tostan/Breakthrough

Tostan has proven to be one of the most promising attempts in history to wipe out what Melching calls female genital cutting, a practice that dates back 2000 years.