GWEN IFILL: Now we have another story in our series on global population issues. It’s a partnership with National Geographic Magazine, which has been reporting on this topic throughout 2011. The September issue examines the declining birth rate in Brazil.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Psychoanalyst Maria Correa de Oliveira says Sunday brunch in her Rio de Janeiro apartment with husband Paolo and their two children is a favorite ritual. It brings back fond memories of her own childhood.

MARIA CORREA DE OLIVEIRA, psychoanalyst (through translator): When I was a child, every Sunday, my father would make fried eggs and bacon for all six of us kids.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: There are two big differences. She grew up in a much larger family, and the Sunday ritual always began with church in this predominantly Catholic nation of 200 million.

Fewer people go to church in the modern Brazil, which is now predominantly urban. Correa de Oliveira says there’s simply no space for large families like the one she grew up in. The extended family all live in Rio and often gather for dinner. It is prepared in the kitchen of their mother, Madelena. She had six children and wishes she had had more.

MADELENA DE OLIVEIRA, mother (through translator): I had one girl, two girls, three girls and then I wanted a boy. So I thought, he should have a friend, but, instead, I had two more girls. I stopped after the sixth child. There were complications. My doctor said that I physically could not have any more children.

In that sense, I was pardoned from the church from having any more children.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Today, her six children have a total of just seven offspring among them, a poster family for one of the swiftest demographic shifts in history.

Brazil’s birth rate is now lower than the U.S. rate of just over two children per woman.

Jacqueline Pitanguy is a leading women’s rights advocate.

JACQUELINE PITANGUY, women’s rights activist: When — Brazil, from six children per woman in the ’60s, we have now 1.9. There has been a dramatic decrease in the numbers of children that each woman has throughout her life.

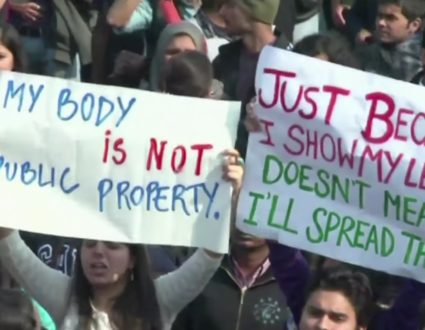

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: She says the shift is the result of a dramatic change in the role women play in society. It was symbolized most visibly by the election of Dilma Rousseff in 2010, the first female president of Brazil.

Brazil’s women’s movement began in the 1960s and was closely allied with groups that resisted the military dictatorship at the time. Pitanguy says it paved the way for new progressive policies by the late ’80s.

JACQUELINE PITANGUY: The new constitution that came when the country was democratized recognizes the role of the state in allowing couples to make free decisions concerning their reproductive lives and the duty of the state in providing information and the means to have this done.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: She says 80 percent of women of child-bearing age use contraception. At the same time, a robust economy has needed their labor. Today, women make up 40 percent of the country’s work force up and down the economic ladder. The majority of college graduates in Brazil are women.

MADELENA DE OLIVEIRA (through translator): For example, my granddaughter wants to be a chef. It never occurred to me when I was a child to be a chef. But I always did encourage my daughters to have a profession and to work.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Today, the women around her table range from screenwriter and physical therapist to systems analyst and business consultant. Women can aspire to any career, but few aspire to have large families. The demands of career far outweigh those of a once-influential Catholic Church, which has long opposed all forms of artificial contraception.

MADELENA DE OLIVEIRA (through translator): I do know a number of Catholic families who have just one or two children.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: What’s noteworthy about Brazil’s declining fertility rate is that it’s happening not just in the growing, prosperous middle-class areas, but also in the poorer sections of what remains a very unequal society.

Despite the economic growth, about a quarter of Brazil’s population remains below the poverty line. Many live in the rural Northeast, but millions have crowded into slums, or favelas, in cities like Rio and Sao Paulo. They suffer from high crime and still lack some of life’s basic needs. But they do have health services, including information about and access to contraception, including sterilization.

These women live in a Rio favela, where they work for a sewing cooperative called Coparaha. Liliane Moreira da Silva has three children, trying unsuccessfully to have a son. She couldn’t control the gender balance of her kids, but she can control the decision to have them, she says.

LILIANE MOREIRA DA SILVA, mother (through translator): You only get pregnant if you want to, because we have free access to any sort of family planning.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Lucelia Carvalho, who is 34, has a six-month-old daughter. Boy or girl, she plans to have only one more child, unlike her grandmother.

LUCELIA CARVALHO, mother (through translator): My grandmother had 10 children, but didn’t have a radio or television. It’s not just television. There are commercials, all kinds of information.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: In fact, television, including the wildly popular soap operas, or novellas, have been a major cultural influence in defining the ideal Brazilian family, says Jacqueline Pitanguy.

JACQUELINE PITANGUY: In the ’70s, these soap operas started to be aired in national chains throughout the country. And they were, you know, associated with the modernity. And modernity was associated with couples with two or three children. And this is very important in terms of a symbolic message, you know?

WOMAN (through translator): It works both ways with the novellas. It goes in both directions.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: We visited Elizete Magalhaes’ living room one evening. The novellas are a stable she can’t resist, she says, engaging and captivating, even though, in some ways, discomforting.

ELIZETE MAGALHAES, Brazil (through translator): In my day, we used to play with dolls. Now kids are playing having boyfriends and girlfriends, like they see on TV.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Psychoanalyst Correa de Oliveira’s life and family may look much like the soap opera ideal. She and her husband just celebrated 25 years of marriage. Still, she wishes her children could have a simpler, carefree life that she enjoyed.

MARIA CORREA DE OLIVEIRA (through translator): What I observe in my work with children and parents is the difficulty in transmitting to the new generation the sort of values that we grew up with, the respect for authority, on how to behave. If religion isn’t the axis from which we’re getting our values — and I don’t necessarily think it should be — what is replacing it? Where are we getting our values?

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: For their part, Catholic Church officials decry the shift among young people to what they see as extreme materialism.

Father Anibal Gil Lopes is with the Rio Archdiocese.

REV. ANIBAL GIL LOPES, Archdiocese of Rio de Janeiro: They want to have cars, houses, objects, but they don’t want to have children or a family. Then this means a change in, I would say, in a philosophy, how you see life, the meaning of life. This weakens a nation.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: This weakens a nation?

He fears Brazil is headed to an imbalance in its population like that seen in many European countries.

REV. ANIBAL GIL LOPES: Confrontation — social confrontations in Europe derives, is due to the fact that the old population cannot be supported by the work of the younger people.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: There are not enough young people?

REV. ANIBAL GIL LOPES: Exactly. There are no people to work and pay taxes.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Ney Costa who heads a family planning advocacy group, says the current birth rate is still much higher than in European nations. He says Brazil can prepare for its more gradual shift.

DR. NEY COSTA, Brazil (through translator): The medical field has grown and evolved. But there are more specialists in such things as geriatrics. And these sorts of things are helping support the older population.

Brazil is far from the crisis that Europe is living. And the good news is that we have time to prepare and implement more policies and mechanisms to sustain this new Brazil.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: He says Brazil has a chance to be the first large nation to get close to a population balance, although demographers say, right now, its birth rate is slightly below replacement.

GWEN IFILL: Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and the Under-Told Stories Project at Saint Mary’s University in Minnesota.

Girl Power

Women can aspire to any career, but few aspire to have large families. The demands of career far outweigh those of a once-influential Catholic Church, which has long opposed all forms of artificial contraception.

“My granddaughter wants to be a chef. It never occurred to me when I was a child to be a chef. But I always did encourage my daughters to have a profession and to work.”

Despite the economic growth, about a quarter of Brazil’s population remains below the poverty line.

Many live in the rural Northeast, but millions have crowded into slums, or favelas, in cities like Rio and Sao Paulo. They suffer from high crime and still lack some of life’s basic needs. But they do have health services, including information about and access to contraception, including sterilization.