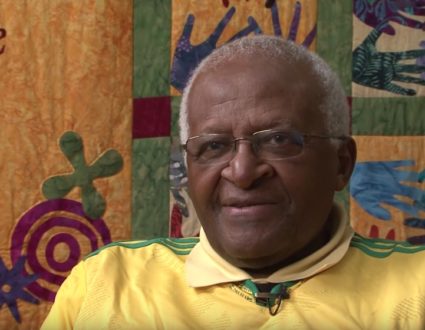

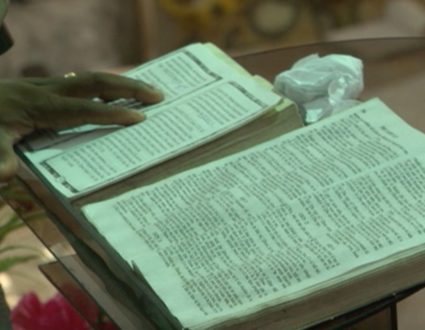

FRED DE SAM LAZARO, correspondent: Every day, hundreds of people gather in a makeshift worship center on the outskirts of Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa.They profess their Judaism in prayers, pictures, and words. They’re hoping to be heard most immediately by authorities in Israel, which they call the Promised Land. Many left spartan farm lives in the rural north of this ancient east African nation and moved to the city years ago in hopes that they, like thousands before them, would be taken to Israel.

Ethiopian Jew: Our members are suffering. They are destitute. They don’t have places to sleep.

Ethiopian Jew: I come to follow God’s word. He said, as I disperse you I shall bring you together. Because of that I want to go back to the Jewish home. DE SAM LAZARO: Their pleas have fallen mostly on skeptical ears even though more than 75,000 Ethiopians, including many relatives of these people, were accepted in recent years into Israel.Their acceptance into Israeli society, however, has been difficult. Many in Israel’s religious leadership have questioned whether the Ethiopians are truly Jewish. Many were subjected to conversion rituals upon their arrival in Israel. In recent years, Ethiopians, particularly in the second generation, have taken to street protests.

Ethiopian Jewish Demonstrator: I think what we are looking here today is thousands of Ethiopians saying here to the Israeli society: no to discrimination, no for racism. All of us we came here to Israel to be equal with Israeli society.

DE SAM LAZARO: The Ethiopian Jewish tradition dates back hundreds of years-many believe more than 2,000 years.

MESFIN ASSEFA (Scholar-Activist): The origin of Ethiopian Jews dates back to biblical times when the Queen of Sheba or Magda first went to visit King Solomon, and she returned bearing a child conceived during this visit. The young prince, later King Melenik, went to Israel to meet his father when he was 20, and he returned to Ethiopia accompanied by 1000 members from each of the tribes of Israel.

DE SAM LAZARO: Other migrations followed from ancient Israel, he says, but this account has a number skeptics.

GETACHEW HAILE: It’s more of a legend than historical truth.

DE SAM LAZARO: Getachew Haile, a religion historian now in Minnesota, says there’s no evidence of any trail linking Ethiopia directly with ancient Israel.

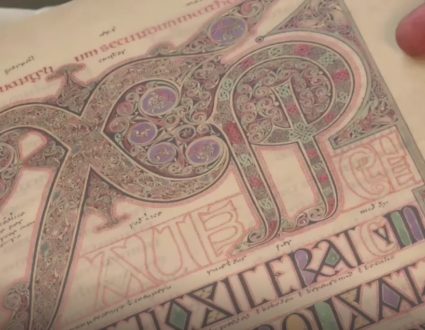

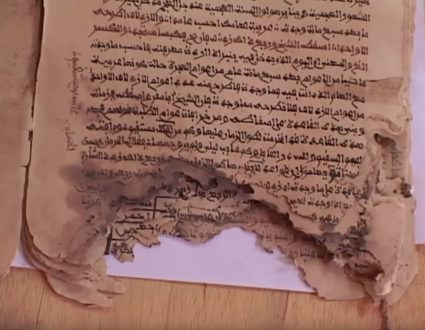

GETACHEW HAILE: We have Greek inscriptions, Arabic inscriptions. There is nothing in the sort of Hebrew inscriptions.

DE SAM LAZARO: More likely, he says, Jews came here from the Arabian Peninsula or Yemen centuries later and settled amid certain isolated populations, helping convert them from the Orthodox Christianity that predominated.

HAILE: One possibility, this is a theory, is that some people might have migrated from over the Red Sea, come into Ethiopia, and converted them. The other is within the Ethiopian community, within the Christian community, who rejected Christianity.

DE SAM LAZARO: Through the ages, he says, some Ethiopian kings enforced a rigid conformance to the predominant Orthodox Christianity. Those outside this system, called falasha or foreigners have been marginalized.

HAILE: They are considered outcasts, and I have no doubt that they have been treated like that within the Ethiopian Christians.

DE SAM LAZARO: Thanks in large part to this persecution, the so-called falasha became Ethiopia’s poorest people, and this has complicated the transition for many who went to Israel from medieval poverty to a First World economy. Still, for the Ethiopians it is a huge improvement in the standard of living. Mengistu Kebede, who’d returned to Addis Ababa on vacation recently to visit family, gave us some perspective. It was a

difficult adjustment to life in Israel, he says, but well worth it.

MENGISTU KEBEDE: It’s significantly better. Everybody wears shoes, they get enough pay for work, their clothes there are nice. Everything is much better.

DE SAM LAZARO: As part of earlier groups who were airlifted amid Ethiopia’s famine and civil war in the 1980s and ’90s, Kebede received a relatively warm welcome under Israel’s law of return. Today, however, the issue of economic motivation has clouded the politics of migration.

ASSEFA: I understand that there’s a perception that people coming from poor countries, from Africa, are coming for the economic benefits. But the issue is it’s the national law of Israel as well as the religious law to allow all Jews to return to Israel. It’s what God promised. As far as we know, all who have applied are bona fide Jews, and while there are advantages, the true motivation is a religious one.

DE SAM LAZARO: Amid the social, political, and economic challenges involving Ethiopian migration, Israel’s government has restricted the number it will allow in. In 2010 the government, in a move that it said should absorb all remaining Jews in Ethiopia, authorized visas for 8,000 new migrants. They’ll be allowed in in phases through 2016. Most of these worshipers did not make the cut. Deliverance to the Promised Land for these people, whose numbers are estimated in the low thousands, could take years, if it happens at all.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Ethiopia’s Jews

Every day, hundreds of people gather in a makeshift worship center on the outskirts of Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa.They profess their Judaism in prayers, pictures, and words. They’re hoping to be heard most immediately by authorities in Israel, which they call the Promised Land. Many left spartan farm lives in the rural north of this ancient east African nation and moved to the city years ago in hopes that they, like thousands before them, would be taken to Israel.

Amid the social, political, and economic challenges involving Ethiopian migration, Israel’s government has restricted the number it will allow in.

In 2010, the government, in a move that it said should absorb all remaining Jews in Ethiopia, authorized visas for 8,000 new migrants. They’ll be allowed in in phases through 2016. Most of these worshipers did not make the cut. Deliverance to the Promised Land for these people, whose numbers are estimated in the low thousands, could take years, if it happens at all.

“It’s the national law of Israel as well as the religious law to allow all Jews to return to Israel. It’s what God promised. “