FRED DE SAM LAZARO: It looks more like a theme park than a school. And it’s not just its location in one of Thailand’s most impoverished regions that’s unusual. Buildings are made of bamboo, including a geodesic dome, just one way Mechai Viravaidya getting people to think differently.

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA, Thailand: Well, just to show that you can do things people don’t normally think can be done, such as getting underprivileged kids to be at the top of the scale of many, many things, of being good, being decent.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The Mechai Pattana School is the cornerstone of an idea to attack rural poverty and stereotypes and to instill a new kind of learning.

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA: This is our sex education wheel.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The “Wheel of Fortune” game teaches about various sexually transmitted diseases.

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA: Green is a safe color, of course. Aha! Oh, aha! HIV, oh boy, you just missed that. And they have a good laugh, and then because HIV is explained up there. . .

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Mechai has long relied on good laughs to explain HIV and sex education in this conservative Southeast Asian nation.

Born to physician parents, his mother from Scotland, his father from a prominent Thai family, Mechai was trained as an economist. But he became a TV personality who spearheaded family planning campaigns in the ’70s and, two decades later, condom use to prevent HIV.

I first interviewed him in 1998.

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA: We said, look, one must not be embarrassed by the condom. It’s just from a rubber tree, like a tennis ball. If you’re embarrassed by a condom, you must be more embarrassed by the tennis ball. There’s more rubber in it.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Mechai is credited with bringing down Thailand’s soaring HIV infection rate and its high birth rate, work that won him numerous international awards, including the $1 million dollar Gates Foundation Prize for Global Health.

Dr. Malcolm Potts, former head of the International Planned Parenthood Federation, says it changed the future of Thailand.

DR. MALCOLM POTTS, former head, International Planned Parenthood Federation: In 1960, Thailand and the Philippines had about the same population, about 60 million people, 50 million people. Today, the Philippines has 94 million people, and there’s a lot of poverty. Thailand has 1.8 children per family. It’s got about 68 million people, and it’s making progress.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Potts was an early collaborator with Mechai. He says population stability was an economic stepping stone.

DR. MALCOLM POTTS: I think it’s a seamless evolution. Mechai, at least in the past, used to talk about fertility-led development.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Thailand, now considered a middle-income country, faces a different crisis that Mechai is attacking: a growing economic gap between its rural and urban areas that forces young people to leave the farms to find work.

On a beach resort once owned by Mechai’s family — it’s now run by a non-profit group he founded — is a garden of so-called intensive agriculture. He wants to develop appropriate sustainable technology to increase incomes in farm families.

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA: This is the new style condom. This is the poverty eradication condom.

(LAUGHTER)

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The unusual metaphor aside, he says these recycled bags of potting soil can grow produce, in this case cantaloupes, with a minimum of water and space and maximum profit.

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA: You’d grow it four times a year, so that’s 34,000 baht. That’s just under a thousand dollars for this much space, nearly as good as marijuana. Might be even better. Don’t have to share with the police, either.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: All joking aside, he says other Thai staples, mushrooms, limes, poultry and hydroponic produce, can easily be grown in rural enterprises, like those he’s helped set up in Buriram Province, about four hours from Bangkok.

He’s worked here for two decades, introducing his crop ideas. Earlier in his career, he helped bring factories to the region. They now operate independently.

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA: You have a factory in the middle of nowhere here.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: This shoe factory was started with international grants. It now provides work for 140 to 200 people, producing mostly for the multinational Bata shoe company.

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA: We helped, from Canadian money again, to provide a loan for them to establish a factory building, and then helped to get Bata to come in, rented the machinery and then bought the machinery, and they’ve been on their own for about 15 years.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: A short distance away are buildings once used to train people to raise livestock. Now they are factories, making brassieres in this building, ice skates in the next.

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA: How could you imagine an old chicken pen and an old pig pen making this stuff, or brassieres?

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Was it really a tough sell at first?

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA: Oh, yes, took seven visits. They did it out of pity at first. And then they realized that it worked. And when the first — when we bring someone new down, they can’t quite fathom it, how can it be done, because they have been so used to the perception that you do everything like this in Bangkok, in the city.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The factories provide livable, if not lucrative, wages and social benefits. But to truly transform rural communities, Mechai says will take new approaches to education.

And that’s where the bamboo school comes in. It is now 3 years old, serving grades seven through 10. Funds to build it came from profits from his resort, the Gates prize money, and corporate donations. Longer term, the school is developing its own vegetable farm, a key part of its business strategy.

So when this is up and running and flourishing, the cantaloupes and the limes will be paying the teacher salaries here?

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA: Yes. Amongst other things, really, yes.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The motto here is, the more you give, the more you get. Aside from academics, every student and family face strict work requirements.

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA: The parents do community service, and the kids do community service, and for every lunch time or meal time you have to do one hour’s community service, so that payment is in providing help to other people, plus their school fees.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: As part of their service, these students were preparing lesson plans to teach younger children in a nearby government school. It’s part of their training in leadership and critical thinking, and a departure from the rote learning standard in most Thai public schools.

RUTHAICHANOK JUNPENG, student (through translator): The teachers are here to teach us, but they’re also like friends, like an older friend that you can go to for advice, not just about what you’re learning.

PIMPAKAIN SIRI, student (through translator): My parents are rice farmers, and I expect my future to be quite different, because I want to become a doctor, and I believe I can do that. I’ve learned new ways to help my parents, who are used to doing agriculture the traditional ways. And I can help raise their income.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: And because students at Mechai’s school regularly volunteer, they feel connected to their rural communities, says teacher Nantina Saninchai. She predicts two-thirds of them will create or find jobs here.

NANTINA SANINCHAI, teacher (through translator): So a number will stay here. They have computers, et cetera, similar to what they would in the city.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Ideas from Mechai’s school are catching on with various backyard enterprises. On weekends in the village of Banong Takem, children collect litter in exchange for spending time online at a community center or in a toy and book library.

Parents prepare food and hand out treats. The village chief, Chamleung Panrin, says one reason this community thrives is that parents are around for their children.

CHAMLEUNG PANRIN, village chief (through translator): Eight years ago, migration was rampant. Everybody would leave, and you only had children being brought up by the grandparents. Now it has very greatly improved.

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA: The only road out of poverty is through business enterprise, and this is what we’re doing. Teach them, train them, lend them the money, not give them the money, and the business skills, but probably very, very important to go with it too is community empowerment.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: And you need to start it young?

MECHAI VIRAVAIDYA: Yes. Yes, start them young. When you start learning how to give when you’re young, when you get older it’s second nature. Just like stealing. Start young and you keep on stealing forever.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Mechai says he won’t mind if more people steal this self-help model of building community and nation.

Building on Legacy

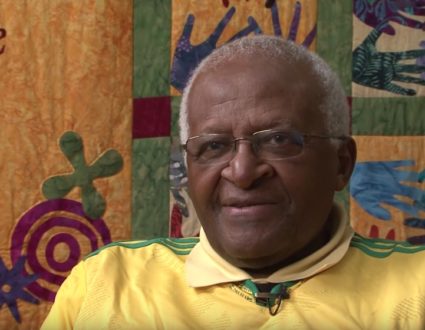

From Thailand, special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports on Mechai Viravaidya’s efforts to combat hardships and instill a new way of thinking in the rural regions of the relatively prosperous country. He’s been a pioneer in health and development in Thailand for over 30 years. Now he has a new focus, education.

Mechai Viravaidya

Mechai is credited with bringing down Thailand’s soaring HIV infection rate and its high birth rate, work that won him numerous international awards, including the $1 million dollar Gates Foundation Prize for Global Health.

The Bamboo School

The bamboo school teaches appropriate sustainable technology to increase incomes in rural farm families

Mechai Viravaidya

“The only road out of poverty is through business enterprise, and this is what we’re doing. Teach them, train them, lend them the money, not give them the money, and the business skills, but probably very, very important to go with it too is community empowerment.”