A Syrian Monastery

BOB ABERNETHY: The spiraling violence in Syria has affected all areas of life, including religious life. The Syrian desert monastery Deir Mar Musa, north of Damascus, was once a center of pilgrimage and interfaith dialogue. But the Catholic priest who leads the monastery was expelled from Syria last month, and the future of his ministry is uncertain. Fred de Sam Lazaro visited before the violence exploded and has our report about Deir Mar Musa and the work once done there.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO, correspondent: So this is where Saint Moses the Abyssinian actually prayed?

REV. PAOLO DALL’OGLIO, Deir Mar Musa Monastery: Yes. This is his house.

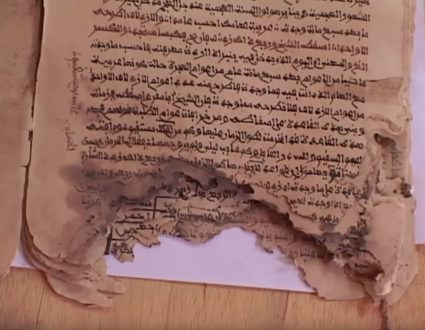

DE SAM LAZARO: About three decades ago, Father Paolo Dall’Oglio happened upon these caves about sixty miles north of Syria’s capital Damascus. It was in these remote mountains that a group of monks from Ethiopia first made a hermitage back in the sixth century A.D.

DALL’OGLIO: You see, this is one of the grottoes of the ancient hermits in this mountain. Now here, we have formed this place in a chapel.

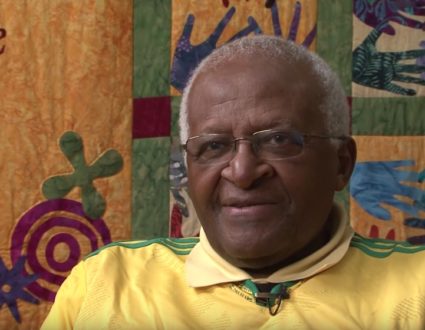

DE SAM LAZARO: Back in 1982, this Italian Jesuit, then 28, was studying Arabic in neighboring Lebanon when he hiked up to this spot for a retreat, a retreat he had to extend because of a serious fall.

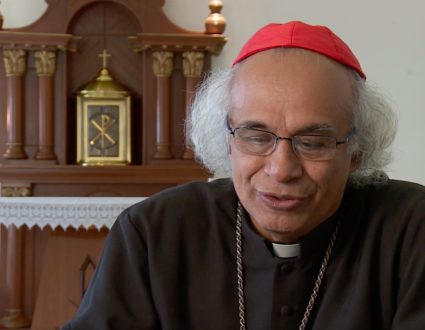

Father Paolo Dall’OglioDALL’OGLIO: There was no way out so I stayed here one week with my broken leg.

DE SAM LAZARO: He did find the stamina to explore the area and ruins of a long-forgotten monastery. It had been used for centuries before being abandoned in the late 1800s.

DALL’OGLIO: I have found really what I was looking for.

DE SAM LAZARO: Dall’Oglio was seeking a monastic life and he got permission from the local church authorities to rebuild and revive this monastery. His first task was to put a roof on this church built in the eleventh century itself on the ruins of a Roman castle.

DALL’OGLIO: I came in the night. And then, I came inside this church. There was no roof so there was an incredible roof of stars.

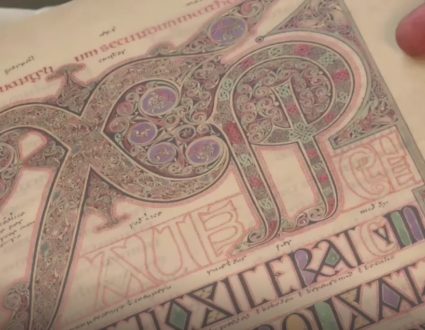

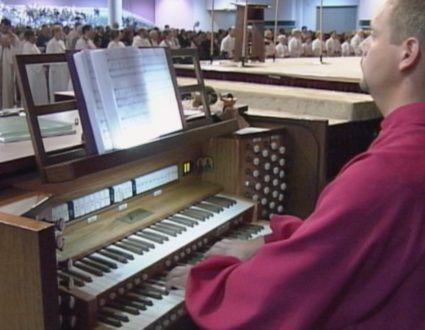

DE SAM LAZARO: It took years and a bit more than half a million dollars mostly from European church and individual donors to restore these almost 1,000 year-old images or those that could be restored. Worship services use a rite of the Syriac Catholic Church, one of the several eastern Christian traditions.

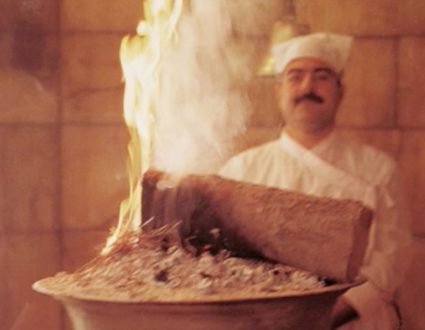

DALL’OGLIO: Here in the name of the Lord, asking for peace, brotherhood and extending consideration, respect, harmony.

DE SAM LAZARO: Traditional as the service is, Dall’Oglio is driven by what he calls a practical theology reaching out and building bridges to the Islamic community, the vast majority of their neighbors. Judaism and Christianity predated Islam in this ancient land but today very few Jews remain in Syria, and Christians account for just ten percent of this country’s population. On the eastern wall of the church, facing the Muslim holy city of Mecca, the Arabic symbol Allah. Christian monasteries were protected as holy places by the prophet Muhammad, Dall’Oglio says. And this one harkens back to a tradition he calls Abrahamic hospitality.

DALL’OGLIO: These people have been in the same villages working with the same people for fourteen centuries. We are together in front of God and recognize each other as believers. In the Islamic town, these Muslim, Christian and Jewish, they worship God in a kind of choir.

DE SAM LAZARO: Father Paolo encourages visits from and dialogue with Muslims, many of whom joined Christian visitors in the climb up 347 stairs to the monastery. Some, like scholar Atas Gomul exploring aspects of Islam’s relationship with Judaism and Christianity, stay for a while to conduct research in the growing library.

ATAS GOMUL, via translator: I was surprised to find so many books about Islam in a Christian monastery. I think it is very good to have a dialogue between the religions, to respect each other and to love one another. Politics always seems to take precedence over religious dialogue.

DE SAM LAZARO: Father Paolo has big plans to continue the dialogue. He’s expanding guest facilities and building a new conference center including, he adds, an access road that will allow those unable to make the long hike to visit.

For Religion and Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro at the Deir Musa Monastery in Syria.

ABERNETHY: In exile, Father Dall’Oglio has become a strong international advocate for peace in Syria. He hopes to return and resume his ministry as soon as possible.

Calm Before the Storm

The spiraling violence in Syria has affected all areas of life, including religious life. The Syrian desert monastery Deir Mar Musa, north of Damascus, was once a center of pilgrimage and interfaith dialogue. But the Catholic priest who leads the monastery was expelled from Syria last month, and the future of his ministry is uncertain. Fred de Sam Lazaro visited before the violence exploded

Reviving a Ruin

It took years and a bit more than half a million dollars mostly from European church and individual donors to restore these almost 1,000 year-old images or those that could be restored.