JEFFREY BROWN: Now the story of a Catholic priest’s journey as a doctor ministering through 25 years of Haiti’s recent history.

Fred De Sam Lazaro has the latest in our Agents for Change series.

A version of this report aired on the PBS program “Religion & Ethics Newsweekly.”

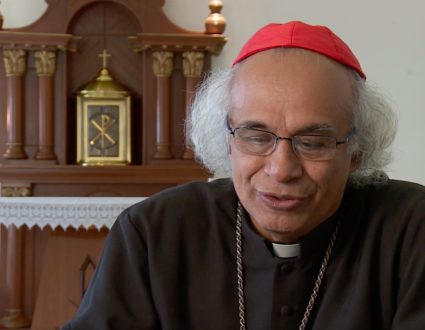

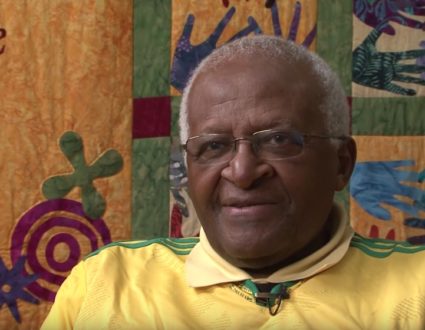

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: For 25 years, Father Rick Frechette’s mission has been defined and redefined as Haiti has lurched through crisis and even catastrophe.

He came to this impoverished Caribbean nation in 1987 after a few years in Mexico and Honduras to expand the mission of his Catholic religious order.

REV. RICHARD FRECHETTE, Mission Leader: We came in fact to set up what we do everywhere, which is a home and school for orphan and abandoned children. We say orphanage. It is just — it’s easier , but the fact is we have community of families. That’s what we have, community of families that have been broken by tragedy.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Today, 800 children whose parents have died or whose families are unable to care for them are housed in several centers.

This one taking in the overflow functions out of converted shipping containers. The shelters’ young managers themselves grew up here, like 22-year-old Billy Jean. His mother brought him here when he was 3.

BILLY JEAN, Haiti: My mother became pregnant very early, about 16 years old, and my father took off, and then my mother couldn’t take care of me. She heard about NPH and she decided to put me there.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: His mother visits occasionally, he says, but the orphanage is very much his family.

REV. RICHARD FRECHETTE: That’s our goal, to restore the family over one generation, to raise the children together so they have memories of their own childhood, restored childhood, and that later in life they become aunts and uncles to each other’s children and their family regenerates after a generation. That’s our goal.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Early in the 1990s came a new challenge for Frechette, children with HIV/AIDS.

REV. RICHARD FRECHETTE: We received some really bad occasions with almost nobody around to manage them and us with nothing but our goodwill to manage them. And that really engraved itself hard on my memory, seeing such terrible things, and honestly not having a clue.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: So Frechette decided to become a doctor. He got his medical degree when he was in his mid-40s. His newly acquired expertise combined with astute fund-raising resulted in a modern pediatric hospital in 2006, the country’s largest. A wing was added for women with high-risk pregnancies which often result in premature births. This way, such newborns are right near the 22-bed center for neonatology.

Dr. Jacqueline Gautier is the medical director.

DR. JACQUELINE GAUTIER, Medical Director: We have central oxygen. We can offer CPAP, which is external ventilation.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: So on any given day, you have 22 kids in here who would not have lived were it not for this facility?

DR. JACQUELINE GAUTIER: Correct.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Then a new challenge, the devastating earthquake of 2010. The quake didn’t damage this hospital, but quickly overwhelmed it.

DR. JACQUELINE GAUTIER: The yard was transformed into a trauma center. We had patients everywhere.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Donations poured in, $9 million in all after the quake, and were used to start a new adult hospital. But 10 months later came a new crisis, cholera, which killed nearly 5,000 people in its first year and continues to flare up, most recently as a result of Hurricane Sandy.

REV. RICHARD FRECHETTE: So we kind of mushroomed out in response to all of these problems. I think the surprise to everybody, including to us, is that we could do it all pretty much without batting an eyelash. And the real wonder of it, to tell you the truth, this is a country of no infrastructures practically, and it’s a country of failed NGOs.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: He says three years after the quake, despite billions of dollars given to thousands of NGOs, non-government organizations, the rebuilding has been painfully slow.

REV. RICHARD FRECHETTE: There’s too much disjointedness. It’s goodwill, and it should be recognized fully as that and appreciated, but it doesn’t get channeled in a way that makes sense, and in fact it’s a way that gets disruptive.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Many smaller NGOs have come and gone as their funding allowed. Bureaucracy has slowed larger agencies and their major projects in housing, clean water and sanitation. Some 360,000 earthquake victims remain displaced in tent camps.

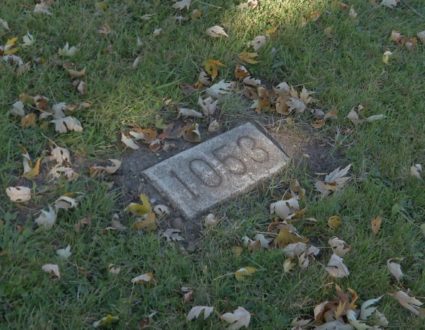

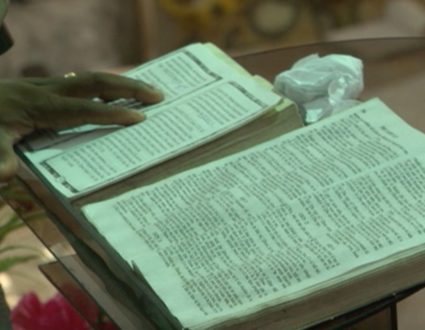

So, the suffering continues and the toll presents itself starkly and literally. Each morning in the chapel of St. Damien’s Children’s Hospital, the shrouded bodies of those who have died, several infants and one adult on this day, are counted, the names written down for prayers that follow at daily mass.

REV. RICHARD FRECHETTE: Anybody that dies in our arms, as they say in Creole, in our place, then their body is first brought to the chapel so that the very next mass, we have the prayers for the dead and for their peace and for the transformation of their life to eternity and for the strength and courage of their family.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Beyond prayer, Frechette says it’s important to strengthen families and communities in development work. Unlike many NGOs, project manager Raphael Louigene says this one tries to involve the community.

RAPHAEL LOUIGENE, Project Manager (through translator): Organizations come in with their own ideas and do things their own way. The way that Father Rick works is we don’t come into a community and give our idea of what to do and how to do it. We listen to the community, listen to their needs because they know them the best, and then we work together to accomplish it.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: In the sprawling Port-au-Prince slum called Cite Soleil, Louigene says the group is partnering with the community to build homes amid a sea of shacks and squalor. They’re built on the principle that if you wait to do things right, nothing will get done for years, only prolonging the suffering.

REV. RICHARD FRECHETTE: We’re investing in the purchase of time. You know, they’re simple block structures, we make most of the blocks ourselves. They’re simple aluminum roofs. It’s more towards normal than anything that they have known, but we’re just buying time while the people with big money and big plans, an interwoven network of organizations can do a proper urban development. That’s what we’re doing.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: They’re also building a new health care facility here. All told, about 1,800 Haitians work for the mission begun by Frechette. Hundreds of thousands have been served in orphanages, schools and hospitals. Funding comes from individuals, foundations and government grants. This year, Frechette was awarded the $1 million Opus Prize, given to a faith-based social entrepreneur by the Minnesota-based Opus Foundation. Frechette doesn’t see his work for the Haitians he serves as charity.

REV. RICHARD FRECHETTE: We give them the chance that we all have had, and rather than saying, I gave you this chance, I say, I was fortunate I had that chance. It came to me. I didn’t make it. And we want that same chance to come to you.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: But, in Haiti, he admits, progress is slow and success built one small stretch at a time.

GWEN IFILL: Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at Saint Mary’s University in Minnesota.

“We received some really bad occasions with almost nobody around to manage them and us with nothing but our goodwill to manage them. And that really engraved itself hard on my memory, seeing such terrible things, and honestly not having a clue.”

Frechette got his medical degree when he was in his mid-40s.

His newly acquired expertise combined with astute fund-raising resulted in a modern pediatric hospital in 2006, the country’s largest.