JEFFREY BROWN: There remains a great deal of confusion about the extent

of the damage in Timbuktu. What is known is that the city, a United Nations World Heritage Site, is home to more than 200,000 ancient manuscripts and other artifacts, spanning many centuries, stored in small private libraries and a large research center.

Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro visited Timbuktu 10 years ago for the PBS program “Religion & Ethics Newsweekly.”

Here’s an excerpt from his report.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: It’s an impoverished town of about 30,000, most of them nomadic traders or subsistence farmers. But Timbuktu is rich in history — history that contradicts a commonly held impression in the West that sub-Saharan Africa has only oral and no written traditions.

SALEM OULD EL HAJJ, Professor: Well before there was an America, Timbuktu was a thriving center of learning, with the university. Professors were teaching philosophy, theology, mathematics.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Professor El Hajj says the earliest records of Timbuktu go back to the 11th century, to a prosperous desert crossroads where salt, gold, slaves, and scholarship were exchanged. That all ended in the late 1500s with Moroccan invasions and later French conquest.

Today, much of Timbuktu’s architecture seems frozen — or, more appropriately, baked in time.

The 15th century Sankore Mosque was Timbuktu’s nerve center of intellectual life.

IMAM ESSAYOUTI, Timbuktu: This place was used for a classroom. In summertime, they gave lectures here. You have a circle here — at least 40 or 45 or 50 students.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Well before Europe’s Renaissance, students and scholars — as many as 25,000 — came from West and North Africa and the Middle East to study Islamic law, theology, and a range of secular subjects.

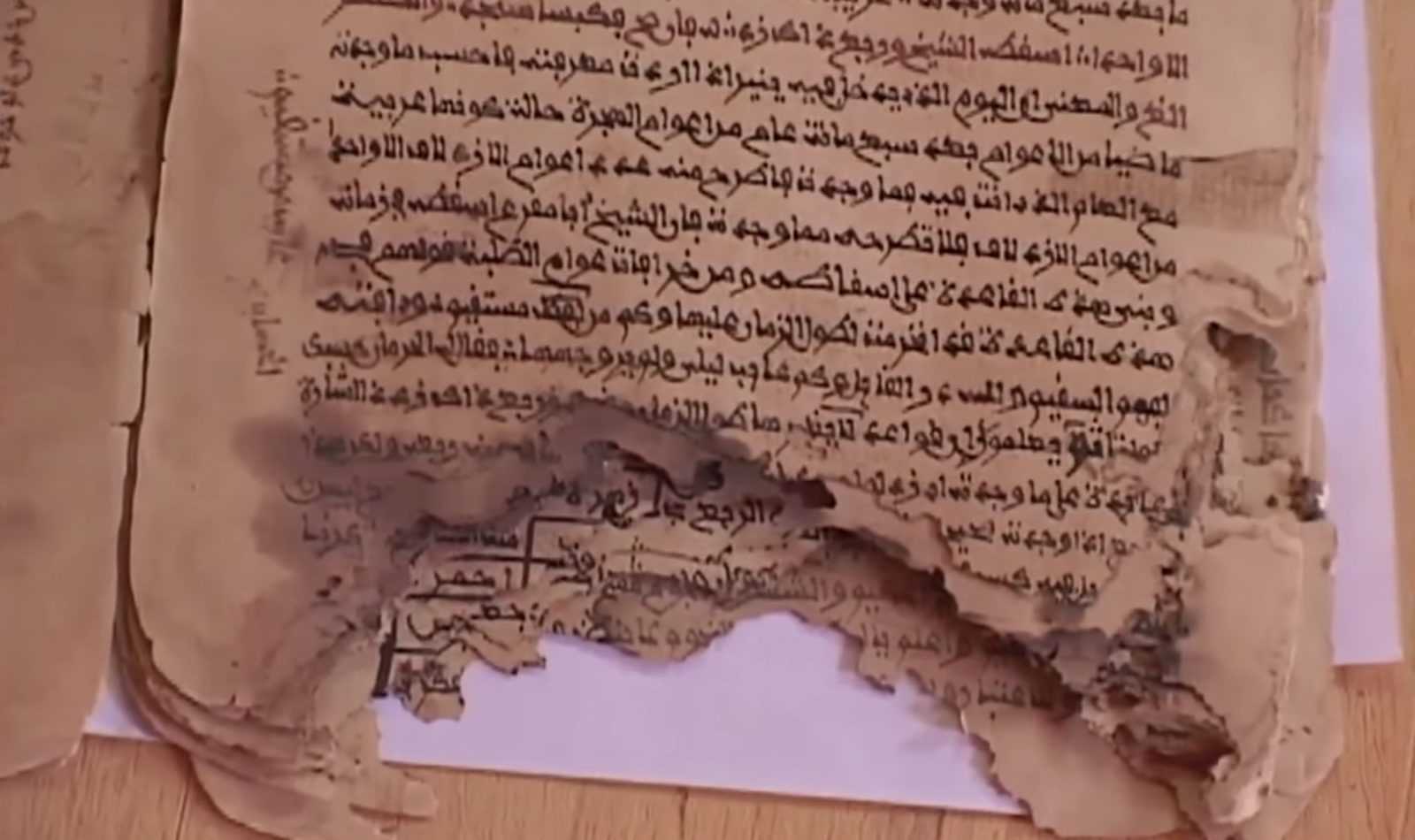

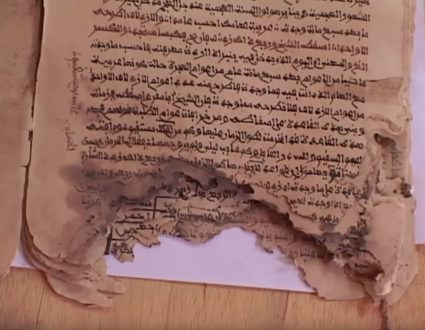

Today, the legacy of that scholarship lies in a vast, scattered collection of historical manuscripts.

ALI OULD SIDI, Guide: Yes, this is the library.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The Ahmed Baba collection, named after a 15th century scholar, with some 40,000 manuscripts.

Arabic was used for theological, as well as secular works — testament to the Islamic world’s leadership during the period in medicine and the sciences.

Every now and then, there’s a manuscript in Hebrew. This one is a 16th century letter by a Jewish trader, writing home to Morocco about market prices in Timbuktu.

MAN: The author is bilingual.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Bilingual?

MAN: Yes.

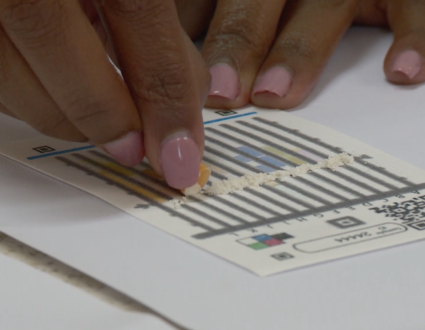

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Despite a wealth of content, the priority now for scholars and manuscript owners, like Abdel Kader Haidara, is the uphill task of saving the crumbling manuscripts.

MAN: So, we have some manuscripts deteriorated by water, by fire.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Their survival is a tribute to the ancient binders. This Koran survived a building collapse. The classic geometric artwork on its goatskin cover is still pristine on the back.

MAN: Seventeenth century.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Seventeenth century?

MAN: Yes. But this is the oldest one.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: 1114.

MAN: 1114, the oldest one.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: A handful of collections, like Haidara’s, have gotten support from universities and foundations in the West to catalog, conserve, and restore manuscripts.

JEFFREY BROWN: And for more, we are joined by Mary-Jane Deeb, chief of the African and Middle Eastern Division at the Library of Congress. She was involved in the digital curation of Timbuktu manuscripts with the help of one of the ancient city’s librarians. The views she expresses here are her own.

Welcome to you.

First, we want to be careful about how much we know or don’t know, right, at this point, because we’re seeing some reports that some of these manuscripts have in fact been saved.

MARY-JANE DEEB, Library of Congress: Absolutely.

And this is the case in many wars. In Iraq, it was the same thing. So the first reports say that everything has been destroyed. But then when we get closer, we see that the librarians themselves saved the manuscripts. The owners of those libraries, the directors, the people who work there are aware of the danger, and they start pulling them out and hiding them.

JEFFREY BROWN: Now, give us a sense of the owners of the libraries. Right? There are private, small private libraries. There’s this one larger research. Tell us a little bit about the place and the libraries.

MARY-JANE DEEB: Traditionally, both in Africa and the Middle East, the owners of those libraries were families who passed those manuscripts from generation to generation. And the eldest son became the librarian, if you want, responsible for the preservation of those manuscripts.

The case in Timbuktu is the same. There are about 32 private libraries, families owning the manuscripts and keeping them. And Abdel Kader Haidara, whom you have just seen, has worked to preserve his own manuscripts, and also those of some of his friends and relatives.

And he has worked with the Library of Congress. And we have over a period of time started to digitize some of those manuscripts.

JEFFREY BROWN: And the manuscripts themselves, spanning many centuries, right, 13th to the 19th, all kinds of subjects? Who wrote them? Tell us a little bit about the work.

MARY-JANE DEEB: Well, it’s wonderful.

They’re scholars. They’re jewelers. They’re travelers. They’re historians. All kinds of people who worked in Timbuktu wrote those manuscripts. So, for example, there are manuscripts on botany and on the medicinal properties of plants which really are relevant even to this day.

There are manuscripts on putting people on trial and the need for proof that the person has been a criminal. There are manuscripts on astronomy, and not just the movement of stars, but how the movement of stars relate to a culture, how it relates to the seasons. There are manuscripts on social conditions, for example, on the issue of inheritance, who inherits how.

There are traditional laws. There are Islamic laws. So there are also manuscripts on politics, you know, manuscripts telling governors and leaders, well, this is as far as your authority goes. And in an Islamic law, those are your limits. They’re fascinating.

JEFFREY BROWN: This all, of course, goes to this cultural heritage of the place that Fred de Sam Lazaro showing a little bit. Tell us a little — this was a very vibrant place of culture, of law, of study.

MARY-JANE DEEB: Absolutely.

You know, it began like — as a commercial center, because it was at the crossroads of North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa. It was also on the route of pilgrims going from North Africa to Saudi Arabia to Mecca and Medina. So, it began as a commercial center. It became very wealthy.

And, of course, when people are wealthy, what do they do? They start building mosques to celebrate and to thank God for their wealth. Those big mosques became centers of learning. And then learned men came on their way to — from pilgrimages, scholars from Cairo, from Fez in Morocco, from Kairouan in Tunisia, came in.

And their own scholars began major debates on issues of religion, of law, and shared scientific knowledge.

JEFFREY BROWN: And that’s the melting pot, right, because of all those different cultures, because it was such a commercial center.

MARY-JANE DEEB: Absolutely.

It was a wealthy center. It was a commercial center. And it was open, open to people coming from different parts of Africa, of the Middle East, and even from Turkey and from Europe. So it was an enormously cosmopolitan, if you want, as well as a learned center.

JEFFREY BROWN: It’s no longer that, and yet it preserves much of that past. I mean, how much is — how much of that life still goes on now?

MARY-JANE DEEB: Well, it’s limited, obviously.

It is still at the crossroads. It is still important in that sense, but it is those manuscripts that are the heart of Timbuktu. It is that that preserves the history of the people who live there. And, of course, the monuments themselves — Timbuktu is a World Heritage Site.

So it remains, like some of the ancient cities, a place of wonder and of beauty.

JEFFREY BROWN: And again with caution, because we don’t exactly know about the results here, but to the extent that things — if things are lost, what is lost?

MARY-JANE DEEB: Well, it’s an enormous amount of knowledge that we will not be able to replace, because it is knowledge created by the people of the region.

It is their knowledge of their tradition, their culture. It is knowledge of plants, of deserts, of skies, of science, of philosophy, of law that really is a universal patrimony, and to lose that is really very sad.

JEFFREY BROWN: All right. Mary-Jane Deeb, thank you so much.

MARY-JANE DEEB: Thank you.

JEFFREY BROWN: And you can watch all of Fred’s story on the Ahmed Baba collection. That’s on our Web site.

The Threat

The city of Timbuktu has suffered extensive damage at the hands of Islamic rebels, including destruction of ancient manuscripts and other artifacts. We get background from special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro, who traveled there 10 years ago, and Jeffrey Brown talks to Mary Jane Deeb of the Library of Congress.

An impoverished town rich in history

The Sands of Time

All kinds of people who worked in Timbuktu wrote the manuscripts ranging from historians, lawyers, astronomers to merchants and botanists.