JUDY WOODRUFF: Next: two stories about combating violence against women.

In Turkey, a fast-changing society has brought new opportunities for women, but also increased domestic abuse.

Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro filed this story as part of our Agents for Change series.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Istanbul presents an elegant blend of history and modernity, a sprawling symbol of Turkeys growing global importance. It is the world’s 16th largest economy.

Modernization has transformed this nation of 75 million from a mostly rural, traditional society to a predominantly urban one. Three of four Turks live in a city today. But by some measures, Turkey ranks among the worst places in the world for women. Women are less educated than men. Far fewer have jobs outside the home. And in the home, half of all Turkish women report having suffered some form of domestic violence.

Inci Kerestecioglu is a sociologist at Istanbul University.

INCI KERESTECIOGLU, Istanbul University: Violence against women in Turkey has increased in response to the demands women are making to become freer, and men feel powerless and resort to violence.

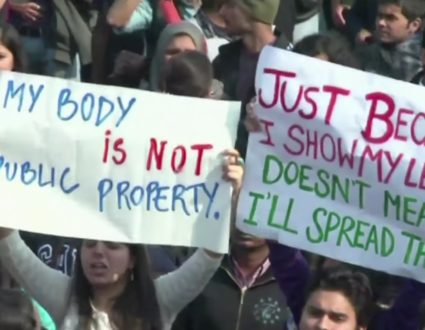

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Women have taken to the streets in recent years. This demonstration was last march. A big problem, many say, is the indifference of police and government officials, even as Turkey’s government reports the number of women murdered in a year in this country went up 1400 percent between 2002 and 2009.

GULSUN KANAT-DINC, Social Worker: They don’t want to deal with this problem, because they don’t see it seriously. This is a women’s issue. That’s why they don’t see it.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Gulsun Kanat-Dinc works for a group called Mor Cati, one of few refuges for women like this 39-year-old mother of three who endured almost two decades of abuse.

WOMAN: My head would be split and bleeding and I would go to the police. I would tell them to rescue me, and they would say, we cannot intervene between a husband and a wife. And he would come, and they would give me back to him.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Mor Cati finds what resources it can and has lobbied for more to help dozens of clients who seek help each day, like this 36-year-old mother of two.

WOMAN: They helped me find psychological support for my children through the divorce. They directed me to a safe house, then took me to the prosecutor’s office for protection under Article 4320.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: That article, a 1998 law that entitles women to protection, was passed with pressure from Mor Cati. It was updated last year by Turkey’s prime minister.

Many of Turkey’s statutes now conform to those of the European Union, which it has long wanted to join. But Kanat Dinc says things work differently here compared to, say, Sweden.

GULSUN KANAT-DINC: If I go to police in Sweden, I will trust police. I wouldn’t have this fear that police would send me back to my home, and they wouldn’t — they would judge me. I wouldn’t have this kind of fear. But if I go to police here, I know that they can easily judge me.

INCI KERESTECIOGLU: Turkey is a diverse country. You can find similarities to Bangladesh, and you can also find similarities to Switzerland within Turkey.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Kerestecioglu says Turkey straddles Europe and Asia not just in geography, but also a complex mix of social mores. She says, although domestic violence affects all income groups, women from migrant families, newly arrived from rural areas, face some of the most daunting strains on family life.

Tradition confines them to the home, but financial pressures — 20 percent in Turkey live below the poverty line — demands they find acceptable work.

SENGUL ACKAR, Foundation for the Support of Women’s Work: They have domestic responsibilities, mainly child care. So, there is no child care services.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Sengul Ackar started the foundation for the support of women’s work 25 years ago to help poor migrant women get what they need to help themselves and their families.

The first challenge was child care. There were very few publicly run preschools, Ackar says, and daunting staffing and building regulations. She says Turkey has long had centralized planning, rigid rules laid down in this case by Education Ministry that prevented private startups, even nonprofit ones.

Her foundation organized and trained women to negotiate with authorities to modify the rules. That’s enabled new parent-managed, cooperative preschools in low-income areas of several Turkish cities.

SENGUL ACKAR: The community, also they feel that this is …

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: They own it?

SENGUL ACKAR: They own it. Plus, for the woman, you need legitimate reasons to go out.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: It’s socially acceptable.

SENGUL ACKAR: Yes, socially acceptable.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The Foundation for Women’s Work provides a range of other services that are socially acceptable to the more traditional migrants. It taps into women’s labor and craft skills, provides small business loans and even markets their products online and in an Istanbul boutique.

EMINE UNAL, Turkey: The products that you see, I started making them just to pass time for my daughter. I knit shoes for babies out of wool and people like them, and I started getting orders.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: This couple is one the women’s foundation helped to straddle two worlds. Emine and Ahmet Unal come from traditional family backgrounds, part of the vast migration to Istanbul for better opportunities. But they want to make a better life for their 6-year-old daughter, Zuha.

EMINE UNAL: I really do want my daughter to have the opportunities that I never had.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Ahmet completed high school, but Emine Unal only went through fifth grade. Women traditionally were less educated in Turkey, but in her case it was state-imposed modernity that kept her home.

EMINE UNAL: I couldn’t go to school because of my head scarf. Even if I would have gone to the school, I wouldn’t be able to find a job because, at that time, nobody would give a job to someone like me with a head scarf.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: That ban on head scarves was part of predominantly Islamic Turkey’s attempt to enforce a rigid secularism, which lasted for much of the 20th century.

But like the rest of life in Turkey, that is slowly changing says Professor Kerestecioglu. Today, Turkey has a conservative prime minister whose wife covers her hair.

INCI KERESTECIOGLU: The main issue here was having conservatively dressed women in the public sphere. As long as these women remained in villages, in traditional roles, the educated didn’t consider wearing a scarf to be an issue. However, when this group came with demands, such as attending university and participating in the public sphere, their demands made the progressive elites uncomfortable.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: For their part, Ahmet and Emine Unal see much more of a blending than a clash of old and new in today’s Turkey.

EMINE UNAL: I didn’t decide to cover my hair because of pressure from my family. It was my own decision, so I’m not going to pressure my daughter to cover her hair. She will make her own decision.

AHMET UNAL, Turkey: It’s her own life. I’m not going to intervene.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Ahmet Unal is also grateful for his wife’s income, having struggled to provide enough from his own work.

AHMET UNAL: I run a cell phone and accessories store, and business is tough because there are a lot of large stores and you can’t match their advertising and discounts.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The Women’s Work Foundation has made a huge difference, Emine says, providing self-confidence, as much as financial help.

EMINE UNAL: This organization represents the soul and the energy of many women. It’s wonderful to just breathe in such an environment.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The foundation Sengul Ackar began has now organized 100,000 women into cooperative enterprises of various types across Turkey.

SENGUL ACKAR: We gave them the confidence, collective confidence that they can change something. They are using their own energies, and they’re providing services for the community, for the others, not for only themselves.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: There’s much more to be done, she says, but the first step to closing Turkey’s gender gap, to reducing problems like domestic violence is giving women a voice.

JEFFREY BROWN: Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at Saint Mary’s University in Minnesota.

The Domestic Abuse Problem

As the Turkish economy has grown and modernized, women have enjoyed more independence. But Turkey’s domestic violence rate has also skyrocketed, leaving female victims feeling helpless to aspects of the culture that haven’t caught up.

Related Links: Mor Cati Women’s Shelter Foundation,Foundation for the Support of Women’s Work

Turkey straddles Europe and Asia not just in geography, but also a complex mix of social mores.

“We gave them the confidence, collective confidence that they can change something.”