JUDY WOODRUFF: Next, from India, worries about the age-old bias favoring male children.

Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro updates a story he did a dozen years ago about the skewed sex ratio of children born in India.

It’s another in our Agents of Change series.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: For some months, Pooja, a 22-year-old mother of three, has been coming to this crisis counseling center in a lower-middle-class neighborhood of Delhi.

Pooja is trying to keep her family together. Her husband and in-laws have tried to throw her out. Their problem: All three children are girls.

POOJA, Mother: The family says they need sons to carry on their name and since I have only three daughters, they tried to trick me into signing divorce papers so that their son could marry again. That led to some violence when I refused, and I had to run away to my mother’s house for safety.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The preference for boys goes back millennia. Boys performed the last rites at their parents’ funeral. They carry the family name and when they marry they bring a dowry into the family.

Dowries were outlawed 50 years ago, but they’re pervasive and mistakenly believed to have roots in Hindu scriptures, says Ranjana Kumari of the Delhi-based Center for Social Research.

RANJANA KUMARI, Center for Social Research: This was never a practice anywhere prescribed, but certainly it was said that when the princess goes, she must carry a number of horses because she’s used to a certain level of comfort. And so it is the duty of the king to insure the daughter is, ensure the daughter is given the — and that gets distorted.

Now even the poorest of the poor who cannot afford two square meals will also have to buy things for the wedding of the daughter.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: With rising aspirations in a rapidly growing economy, daughters have become an increasing financial liability for their families, says sociologist Ravinder Kaur.

RAVINDER KAUR, Indian Institute of Technology: That don’t want to pay dowries, they want to receive dowries. They want to give more education to the boys than to the girls because for them the boys are still more important.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: And the census shows Indians are acting on that bias. For every 1,000 male infants born, there are just 914 females, in some regions, far fewer. In nature, those numbers are about equal.

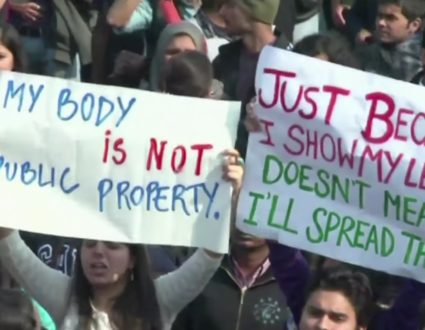

The gap began to widen in the ’90s with new ultrasound machines that made it easy to learn a fetus’ sex. These scans have led to the termination of millions of female pregnancies. In Delhi, the Center for Social Research has organized women into neighborhood groups trying to shift the ingrained gender bias, even invoking Hinduism’s goddess of prosperity.

WOMAN: We must begin to welcome girl babies into our homes, like the goddess Lakshmi has come into our home.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: They’re also made aware of the law that’s become known by its English acronym. That’s the Preconception and Prenatal Diagnostic Technology Act. Abortion is legal in India, but the act makes it illegal when done for sex selection.

RANJANA KUMARI: A lot of people don’t even know that we have a very strong law. If you, A., go for sex selection and also the doctor, the clinic, the radiologist can go to jail up to seven years if they’re caught doing it. We’re trying to tell people, instill some fear in the minds of people that should not go for sex selection.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: However, absent extensive surveillance and sting operations — and they have been absent — it’s difficult to police something that happens in the privacy of a doctor’s office, as one obstetrician told me in a NewsHour report on the same subject that I produced 12 years ago.

Prakash Kakodkar candidly admitted he performed sex-selected abortions routinely.

So you freely admit that you do, basically, contravene the law, I mean …

DR. PRAKASH KAKODKAR, India: Yes, most of us do, I would say. I won’t deny that.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Do you face any legal sanctions?

DR. PRAKASH KAKODKAR: No, that’s what I said. There is no legal sanction because there is nothing on paper. I mean, who can ask you?

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: So despite the efforts of activists, in the two decades since it was outlawed, only 46 sex selection cases have been brought against medical practitioners, with just one, one single conviction.

Meanwhile, census figures show the practice has become even more prevalent. Two decades ago, it was mainly in the northern farm states, whose green revolution had moved a lot of farmers into the middle class. Today, that middle class and lopsided gender ratio have spread widely.

RAVINDER KAUR: Places like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Orissa, which are becoming more prosperous where there will be greater availability of technology and more incomes in the hands of families, they will tend to shape the family and sex select.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Here’s a huge irony: As these areas become more affluent, fertility rates, the number of children born per woman, are declining. That’s good news, especially in some of India’s most densely populated states. But when it comes to gender balance, it’s not good news.

RAVINDER KAUR: You know when you want a smaller family, then the squeeze is on the girls, because, interestingly, suppose you’re moving from a fertility rate of four to three. Then you want two boys and one girl. So if a lot of families in populous states want two boys and one girl, then obviously there’s going to be a great excess of boys.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Kaur is seeing the consequences that she says are already becoming visible in those northern farm states. A shortage of brides is forcing men into marriage outside their communities, very awkward in a tradition-bound society.

RAVINDER KAUR: Men in these states have been importing brides from let’s say the east of India, the south of India. They’re sort of going shopping for brides wherever they can.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: At the same time, Kaur sees a slight improvement in the gender ratio in the states that saw skewed ones early on. She attributes this to growing affluence.

RAVINDER KAUR: Once people reach the higher rungs of the middle class, which I call the stable middle class, they don’t sex select. Then they tend to view girls and boys as being of equal value. So they don’t really care whether they have two girls, whether they have one girl, one boy, et cetera.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: She admits it will take many years and vast numbers making it into the stable middle class to correct India’s gender ratio. The Center for Social Research’s Kumari sees one other hopeful development that is also tied to India’s growing and middle class. More girls are going to school.

RANJANA KUMARI: India is full of contradictions. On the one side you see women in the villages still very disempowered, but on the other side there is a brighter picture. We have the largest number of doctors, lawyers, professionals. Our education level is going up for the girls.

Women are filling the ranks in a very major way.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Counseling center client Pooja never set foot in a school, but she wants an education for her daughters. That’s why she’s pursuing the uphill battle to stay married.

POOJA: Women are progressing more in society and I need the support of their father so that they can grow up in a proper family, so that they can get a good education, so that they can grow up and have good marriages.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The best dowry for a young bride, she and many others say, is an education.

JUDY WOODRUFF: A version of Fred’s story aired on the PBS program Religion & Ethics Newsweekly.

His reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at Saint Mary’s University in Minnesota.

Bias for Boys

Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro returns to a story he first reported on 12 years ago about the skewed sex ratio of children born in India. Baby boys are seen as more favorable for both economic and cultural reasons, a perception activists are trying to combat.

The preference for boys goes back millennia. Boys perform the last rites at their parents’ funeral. They carry the family name and when they marry they bring a dowry into the family.