JUDY WOODRUFF: It’s been almost a year since a Bangladesh factory collapsed, killing more than 1100 garment workers and injuring 2500 others.

Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro returned to the country recently to see what’s been done to make factories safer and whether victims of the disaster have been compensated.

His report is a partnership with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: We first met Josna Akthar last June in a Dhaka hospital. She had been rescued after spending two days under the rubble of Rana Plaza.

Doctors said Akthar was lucky to survive the building collapse that claimed more than 1,100 lives and fortunate that her spine remained intact. That’s not the way she feels today.

JOSNA AKTHAR, (through interpreter): Sometimes, I wonder how I can continue this life. I cannot do anything. If I bend to pick up anything from the floor, it really hurts. Sometimes, I say it might be better to die.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The 19-year-old says she’s in almost constant pain, unable to sit or stand for more than a few minutes at a time. We had to interrupt our interview so she could stretch.

JOSNA AKTHAR (through interpreter): I had surgery on my spinal cord, and the doctors said not to do any hard work, because that could hurt my spinal cord. They said it could take a long time to heal.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: So, most days are spent in bed watching TV in the tiny one-room home she shares with her parents and two younger sisters. She was a breadwinner until last April. Now she frets being a burden. Her mother, Rahela Begum, also had to quit her garment factory job.

RAHELA BEGUM (through interpreter): I have to care for her, and there is no way that I can take a job outside of the house. Our big concern is how long she will be this way, about her future.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: They are like millions of impoverished rural families who have moved to the capital city in recent years to work in the garment industry that’s second now only to China’s in size.

Josna’s father’s earnings as a rickshaw-puller, about $3 a day, are all this family has.

RAHELA BEGUM (through interpreter): When she was in the hospital, people took down her name, and I have heard of people getting compensation but no one has contacted us.

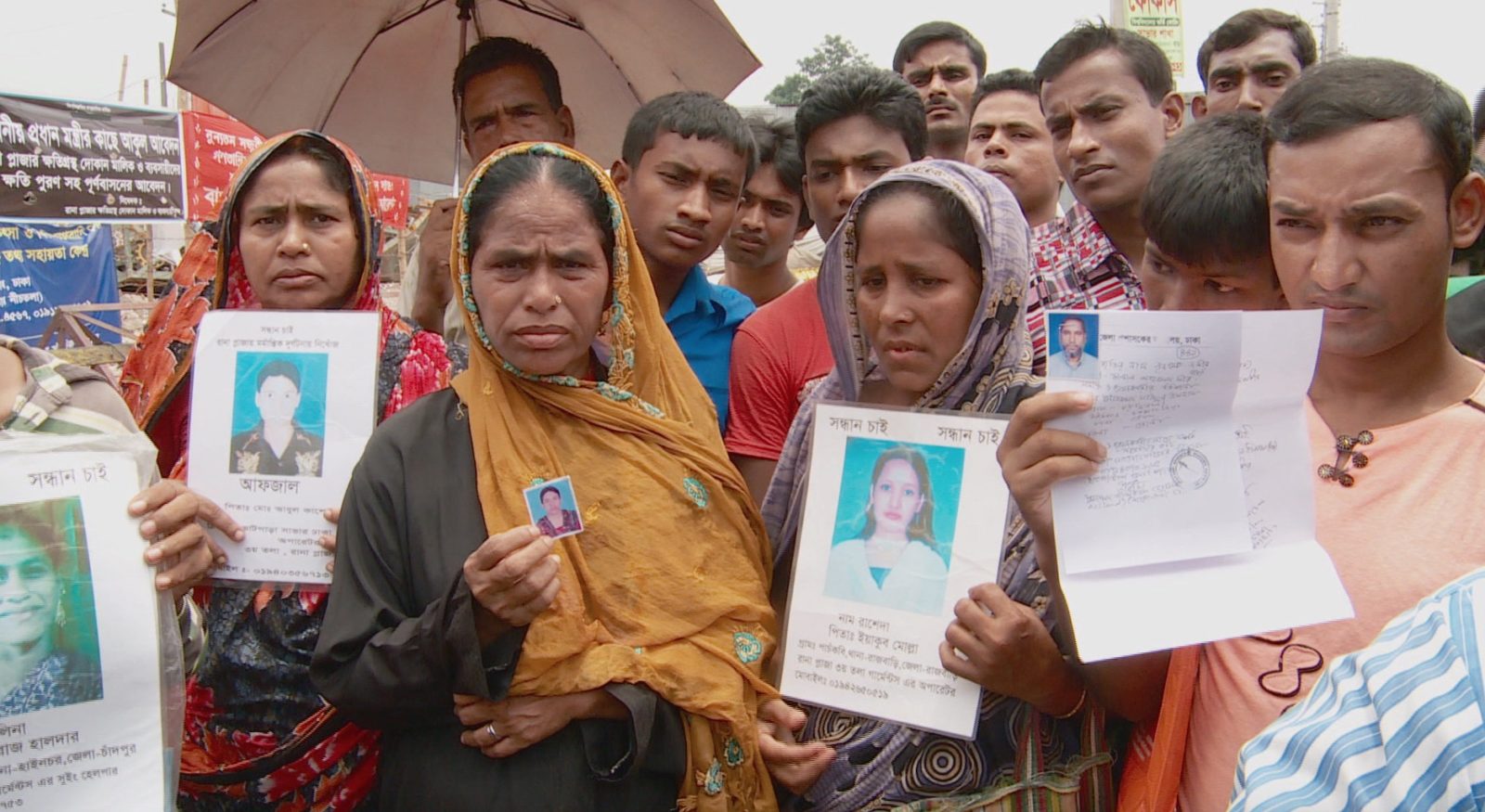

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: When they learned of our visit, several neighbors gathered around, clutching pictures of relatives who died in the building collapse. Some said they had received just 1,300 U.S. dollars from a government fund. Some complained it had gone to the wrong family members.

There are no reliable records of who worked in the building or which companies had contracts and therefore might bear responsibility for compensating victims. Add red tape on top of that, and relief has been slow to reach victims and families, says labor organizer Roy Ramesh.

ROY RAMESH, Labor Organizer: It is the fault of the government, fault of the employers, fault of the buyers, and everyone. Nobody can deny the responsibility of that.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: All but the workers, he says, have benefited from an opaque trade that relies on low wages and lax regulation.

After Rana Plaza, the image of many global apparel companies was threatened, says Scott Nova. He’s the Washington, D.C.-based Workers Rights Consortium.

SCOTT NOVA, Executive Director, Worker Rights Consortium: These are brands and retailers who work very hard to create as much distance as possible between the reality for the workers who make their products and the consumers who buy and wear those products. But an event like Rana Plaza closes that distance. It shows consumers the conditions under which their clothing is being made, and it creates, therefore, strong pressure on the brands and retailers to change their practices.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: In general, he says European brands have acted more responsibly; 153 companies recently signed onto a legally binding multimillion-dollar worker safety accord to respect and bring all factories up to international building standards.

Most big American names didn’t join this group. A few did.

SCOTT NOVA: We have Fruit of the Loom. We have PVH, which owns Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger, and a number of others. We also have brands that are not U.S.-based, but household names in the U.S., like Adidas, like H&M. So some companies involved in the U.S. market are stepping up, but the Wal-Marts, The Gaps have not chosen to be part of this critical process of change, and that is extremely disturbing to watch.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Some experts say liability concerns have kept the American companies from legally binding commitments, but Rabin Mesbah, local head of the U.S.-led group, says just because they didn’t sign doesn’t mean they have done nothing.

RABIN MESBAH, Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety: First is a gentleman’s commitment.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: A gentleman’s commitment?

RABIN MESBAH: Commitment and understanding and perception, not necessarily has to be legally binded.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: He says his so-called Alliance group has hired international and local engineers to do safety inspections at garment factories.

RABIN MESBAH: We are trying to engage the workers. We are establishing the outline to listen to their voice, so we will make it as safe as possible.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: And the Alliance has collaborated with the European-led group on common safety concerns, jointly sponsoring a recent building safety expo, for example. It introduced owners of the 4,000-odd factories to things like fire doors and sprinklers, virtually unheard of in Bangladesh.

For their part, factory owners like Shabbir Mahmood complain that their international customers have talked about improving conditions, but haven’t been willing to pay for it.

SHABBIR MAHMOOD, Factor Owner (through interpreter): Whenever I ask the buyers to give a better price, the buyers say, we will go somewhere else.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Besides building improvements, factory owner group Atiqul Islam says wages were recently increased. The legal minimum offered workers has gone up from about $38 a month to about $70 a month.

ATIQUL ISLAM, Bangladesh Garment Manufacturing and Exporters Association: What are saying to them, that we have increased our salary, as you know that, last December, new salary structure has been declared by our government. So, the buyers, still they are not paying the…

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The buyers are not paying you more, even though you raised the wages?

ATIQUL ISLAM: Absolutely.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Workers’ representatives complain that wages, even with the recent increases approved by the government, are still well below what’s considered livable in Bangladesh.

Labor organizer Ramesh says there is a long way to go on other rights workers are supposed to enjoy.

ROY RAMESH: The international buyers should use their business influence, so that the workers are enjoying the freedom of association, collective bargaining. And government is reluctant to implement the existing laws.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Government is greatly influenced by the garment industry, he says. Many members of parliament also own garment factories.

For his part, the country’s commerce minister says he’s proud of the industry’s accomplishments. In two decades, it’s brought four million workers out of dire poverty, says Tolfeo Ahmad. And the Rana Plaza tragedy will make the multibillion-dollar ready-made garment business more transparent and prosperous, he says.

MAN: Today, $21.5, and in 2021, it will be $50 billion.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: More immediately, government and officials insist that families affected by the Rana Plaza tragedy will soon begin receiving compensation.

The British retailer Primark announced a $9 million fund to help some 500 families of workers who produced its garments in the building.

For her part, Josna Akthar hopes someday to return to a job that helped support her family, one that allowed a rural Bangla teenager to fantasize about the world beyond.

JOSNA AKTHAR (through interpreter): I wanted to meet people who wear the clothes made by workers like us. So, for fun, when we were making shirts, I put my mobile number in the pocket of the shirts. I knew that the people who wear these shirts could not speak Bangla, so I write in English, “If you like the shirt, call me.”

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Did she ever get a call?

She got three calls, she says, limited by the language barrier to no more than a brief greeting. That was before her cell phone was lost in the collapse of Rana Plaza.

JUDY WOODRUFF: Late last month, three major U.S. retailers said they would provide compensation to victims of the building collapse. Wal-Mart contributed $1 million, and Children’s Place and Gap gave half-a-million dollars each.

Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at Saint Mary’s University in Minnesota.

A Year After Tragedy

Almost a year has passed since a Bangladeshi factory collapsed, killing more than 1,100 garment workers. What has been done in that country and by the international garment industry to make the factories there safer? And how have the victims and their families been compensated? Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro returns to Bangladesh to find out.

Related Links: Guardian: Bangladesh Factories Still Exploiting Child Labor,WSJ: Strife Curbs Progress in Bangladesh Garment Industry

The Rana Plaza collapse claimed more than 1,100 lives.

Josna Akthar was rescued last June after spending two days under the rubble of Rana Plaza.