GWEN IFILL: This month marks the 20th anniversary of the genocide in Rwanda. Over the course of 100 days in 1994, a murderous ethnic killing spree took the lives of nearly one million people there.

Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports on the efforts under way even now to reconcile the rival parties.

Fred’s report is part of our series Agents for Change. A version of this story aired on the PBS program “Religion & Ethics Newsweekly.”

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Every Sunday, Claude Musayimana picks up his neighbor Celestin Buhanda on their way to church. You’d never tell from the warm traditional greeting that Musayimana murdered several members of Buhanda’s family.

It’s a friendship as unthinkable as the homicidal orgy in which Hutus like Musayimana killed nearly a million of the minority Tutsi like Buhanda, as well as some moderate Hutus.

CLAUDE MUSAYIMANA (through interpreter): Growing up, I remember my grandmother would tell me how bad they were. In 1994, when we started killing people, the local leaders were supporting us. I did it freely. There was no blame, no consequences.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Official broadcasts incited Hutus to kill Tutsis after an airplane carrying the country’s Hutu president was shot down, escalating a simmering civil war fought along ethnic lines.

The tension dates back decades, aggravated first by Belgian colonial rulers who favored the minority Tutsi. That created an elite and bred resentment among the 85 percent Hutu majority in Rwanda. In ethnic flare-ups, churches had served as safe havens. Not in 1994. They became killing chambers, in some cases with the complicity of their pastors.

CELESTIN BUHANDA (through interpreter): I fled to the church in Ntarama. The only reason I survived is that it was so crowded we decided to allow only women and children to shelter inside the church.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: All 5,000 women and children in the church were killed with guns or grenades.

CELESTIN BUHANDA (through interpreter): We were eight siblings; in all, six of them were killed.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: He survived a weeks-long flight and encounters with Hutu mobs who left him with blows to the head, a severed Achilles’ tendon and left him for dead.

CELESTIN BUHANDA (through interpreter): The killings continued until the RPF arrived.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The RPF, or Rwandan Patriotic Front, an army led by exiles from neighboring Uganda, took over the country. It drove genocide leaders and millions of Hutus into neighboring Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of Congo. Thousands of most Hutus were killed in reprisals.

RPF leader Paul Kagame consolidated power, became Rwanda’s president in 2000, and has since won two elections.

CLAUDE MUSAYIMANA (through interpreter): After the RPF came to power, I fled to the south. I felt guilty about the innocent people I’d killed. I decided to come forward and tell the truth. I was arrested and put in prison.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Musayimana spent 10 years in prison. Like him, many perpetrators are now out and returning to their communities – an integration that would be difficult in any circumstance in this crowded country, 12 million people squeezed into a land the size of Maryland.

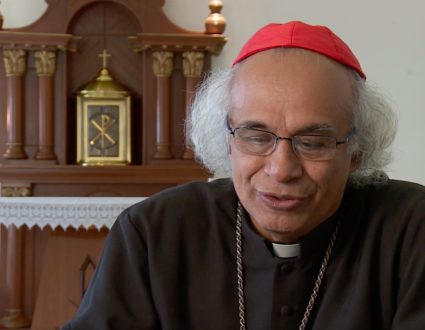

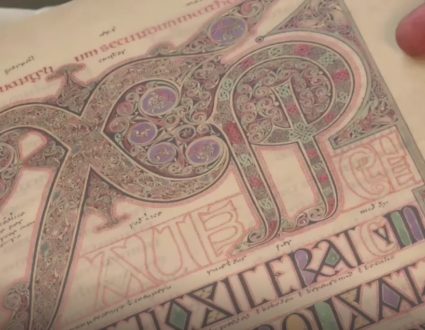

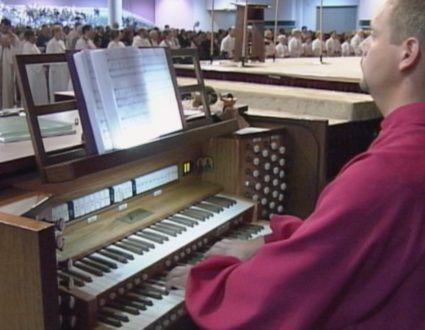

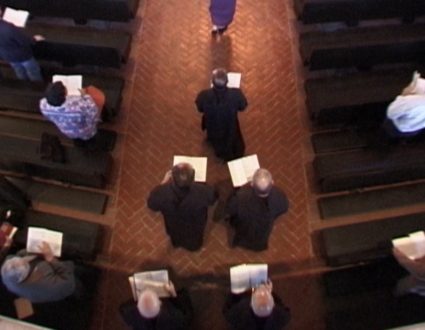

Rwanda’s churches, so many of them complicit in the genocide, so many of them the very site where massacres occurred, are being asked to play a key role in the reconciliation that will be essential to rebuilding this country.

Claude Musayimana and Celestin Buhanda met in one of many small groups set up by the Christian charity World Vision. It organized regular meetings that brought genocide survivors face to face with perpetrators.

CLAUDE MUSAYIMANA (through interpreter): The workshops were very important. For many years, I kept wondering what I could do to be free, to be accepted back in the village. This was an opportunity.

CLAUDE MUSAYIMANA (through interpreter): It wasn’t easy. We yelled at them at first, and that allowed us to feel relief, and we were able to find space in our hearts to forgive.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Today, the former workshop groups serve as clubs, organizing projects to build homes for genocide survivors or on projects like this tree nursery, trying to move forward as one community despite ever-present reminders and pain.

Alice Mukarurinda lost not only her infant daughter, but also her right hand. She bears a deep facial scar, among other injuries. She met her assailant, Emmanuel Ndayisaba, six years ago in this group.

ALICE MUKARURINDA (through interpreter): All those years, I looked at all Hutus as the ones that did this to me. I prayed to God that if I could meet the one person, I would shift the blame from all Hutus to him.

EMMANUEL NDAYISABA (through interpreter): I saw visions of the people I killed for many years. It was painful. I was a Christian, an Adventist. I was in the choir. All that guilt made me sick.

ALICE MUKARURINDA (through interpreter): When I first saw him, I was so traumatized. I had to be taken to the hospital for 10 days. It was not easy. But then later, I managed to forgive him. I believe it was God’s power.

EMMANUEL NDAYISABA (through interpreter): We have built 118 houses so far. That’s one of the things we do to pay back what we did, the genocide. I spent eight years in prison, came out, and did two years of community work. But it never feels like enough.

ALICE MUKARURINDA (through interpreter): The fact that we are given the time to speak out about our feelings made us feel much better. We had kept all the sorrows and pain in our heart. It was so painful.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: It helped that her attacker was literally working for forgiveness, building houses for people who were harmed in the genocide.

JOSEPHINE MUNYELI, World Vision: I see real reconciliation is taking place, and it’s not fake. It’s genuine. Well, you cannot fake reconciliation. You can’t.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: World Vision’s Josephine Munyeli says so far her group alone has brought rapprochement between more than a thousand pairs of genocide survivors and perpetrators. But there’s no escaping it will be a long journey.

JOSEPHINE MUNYELI: The challenge is the magnitude of the genocide. It was very deep. It was awful. It was very bad, and they – and you cannot exhaust it. You heal, but when – another day, you remember another story.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Rebecca Besant has been working to make sure reconciliation keeps moving forward among younger Rwandans. She heads the Rwanda office of a group called Search for Common Ground.

REBECCA BESANT, Search for Common Ground: The fact that you know your neighbor killed your entire family and now you’re still in the house next to them and have to see them every day, a lot of people have sort of decided, I don’t have a choice. And either I can let my rage absolutely consume me, or I can accept the fact that I’m not going anywhere, and he’s not going anywhere, and we have to make this work.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Her agency uses a reality TV show to encourage entrepreneurs, trains journalists in a country where media were used to incite the genocide, and works in schools.

Many of today’s youth were orphaned by the genocide. Others have parents in prison. Through drama skits, this troupe encourages students to come together as Rwandans first.

REBECCA BESANT: One of the things that we’re really trying to encourage for Rwanda in the future is how to talk about things before it explodes. If you’re a young person and you’ve got a problem in your classroom, how do you express what that problem is? And you talk about it in a frank and open way. And I think that continues to be one of the challenges.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: One thing that she and others say is helping Rwanda heal is that the economy and access to services like health care have improved markedly in recent years.

GWEN IFILL: In our second report tomorrow, Fred looks at those improvements.

His reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at Saint Mary’s University in Minnesota.

20 Years After Genocide

Twenty years after nearly a million Tutsis were killed the genocide in Rwanda, many Hutus — who were driven out in retribution — are returning to their communities. To facilitate the integration, many small groups are bringing rapprochement between pairs of genocide survivors and perpetrators. Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports on Rwanda’s journey toward healing and forgiveness.

Rwanda’s Churches

Rwanda’s churches, so many of them complicit in the genocide, so many of them the very site where massacres occurred, are being asked to play a key role in the reconciliation that will be essential to rebuilding this country.

REBECCA BESANT

“The fact that you know your neighbor killed your entire family and now you’re still in the house next to them and have to see them every day, a lot of people have sort of decided, I don’t have a choice. And either I can let my rage absolutely consume me, or I can accept the fact that I’m not going anywhere, and he’s not going anywhere, and we have to make this work.”

Face to Face

Workshops hosted by religious institutions brought survivors and perpetrators together to talk and work on community projects