GWEN IFILL:The World Health Organization reported today that the Ebola virus has now killed more than 2,800 people in West Africa. The majority of deaths have been in Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone.But the deadly illness has been relatively contained in nearby, and much larger, Nigeria, which counts 21 cases and only nine deaths.Tonight, special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro takes a look at how Nigeria has controlled Ebola’s spread.Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Not much moves in a hurry in Nigeria’s commercial capital, Lagos, also Africa’s most populous city.And basic services, like roads and covered sewers, have yet to reach slums like Otumara. But the Ebola message has, what it is, where to report it, how to prevent it.

MAN:You need to wash your hands. It’s very, very important for you.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Nigeria’s Ebola response has been comprehensive in communities and the media. There’s temperature screening at all the country’s entry and exit points — fever is an early warning sign — and extensive surveillance by public health workers. It’s driven by sound epidemiology and, the American consul in Lagos, Jeffrey Hawkins, says, fear.

JEFFREY HAWKINS, U.S. Consul General:One thing that people really don’t want to hear is Ebola and Lagos in the same sentence. This is a city of 20 million people, and a major urban outbreak here could have been apocalyptic. But the response was quick.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:One early leader of that response was Babatunde Fashola, governor of Lagos state, which includes the city.

GOV. BABATUNDE FASHOLA, Lagos State:On this kind of job, fear is always healthy. If you lose fear, something is wrong.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Nigeria’s response began soon after the first confirmed Ebola case in late July. A Liberian-American traveler fell ill at the airport at Lagos. His circle of contacts was limited to the health workers who cared for him, and then there were their contacts. One of them carried the infection to the southern city of Port Harcourt, causing a second outbreak.

DR. FAISAL SHUAIB:Within a question of just a few days, we had as many as 500 contacts that were being traced, just to cast a wide net and ensure that anybody that has potentially had any contact with a case is under our purview, taking temperatures, asking them if they have any symptoms.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Dr Faisal Shuaib of Nigeria’s Health Ministry heads the Ebola command center. The response team includes several international agencies that have been in Nigeria for years fighting other diseases, like malaria, HIV and polio.They quickly redeployed. Dr. Nancy Knight, with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, says the CDC had earlier trained many field epidemiologists here.

DR. NANCY KNIGHT, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: One of the things that has really helped keep the fear in check and to keep it from turning into widespread panic has been the number of boots on the ground. We have had, between Lagos and Port Harcourt, more than 1,000 people that have been working on containing the epidemic.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Despite Nigeria’s many problems, sectarian violence, Boko Haram insurgents kidnapping schoolgirls, the country has a more developed public health system than its smaller neighbors reeling from Ebola. Having international experts on hand also helped reassure key political leaders like Lagos’ governor.

GOV. BABATUNDE FASHOLA:That helped a lot to make decisions and to communicate with all of the stakeholders, religious leaders, primary health care workers, school teachers to reassure them that we could turn this around.

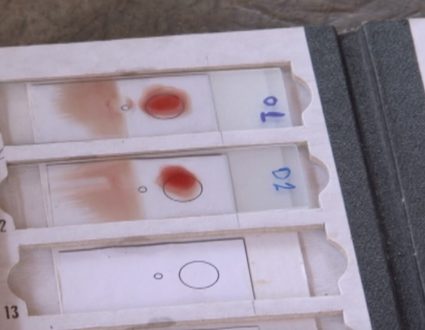

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:The aid group Doctors Without Borders has trained health workers on handling patients, on using the airtight personal protective equipment. The group has built isolation centers in Lagos and Port Harcourt that would handle a fresh outbreak. For now, there’s just one suspected case left.There’s no panic, but there’s still a lot of stigma surrounding Ebola in Nigeria. As outsiders, as a camera crew, we were not allowed to go near the contact tracers. These are public health workers who fan out each day to keep tabs on people who had any contact with someone infected with Ebola.Dennis Akagha knows firsthand about stigma.

DENNIS AKAGHA:I lost my job while I was taking care of Justina.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:And he lost Justina, his fiancee who was two months’ pregnant. On her first day on a new job, the 32-year-old nurse’s first patient just happened to be that first Ebola case, the Liberian-American. Akagha too became infected, but he pulled through. Survivors of Ebola become immune and are no longer contagious. But that hasn’t helped Dennis Akagha.

DENNIS AKAGHA:Ebola is not a death sentence. I wouldn’t have lost my job if they had been informed.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Early detection has helped the survival rate in Nigeria. Fewer than half the cases have resulted in death. But the stigma only worsens the public health threat, says Dr. Ndadilnasiya Waziri, who heads the contact tracing effort.

DR. NDADILNASIYA WAZIRI:A lot of contacts that were (INAUDIBLE) couldn’t even come out to get food in their communities because they were being stigmatized. So, that’s a big worry because that will make people to hide.

WOMAN:Washing of our hands regularly is one of the best ways to avoid and prevent all of these diseases flying around, like Ebola.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Nigeria’s influential film industry, popularly called Nollywood, has stepped in to help.

TUNDE KELANI, MOVIE Director:This is like — like UFO, you know, suddenly descended on Nigeria, you know, and we had to do something about it.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Tunde Kelani, a top director, says Nollywood’s leading lights came together in record time, responding, he says, to the biggest existential threat anyone here has felt.

TUNDE KELANI:I think they responded very well, because we put together a list of about 18 of these celebrities.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Now he’s thinking, why not expand the idea beyond this Lens on Ebola effort?

TUNDE KELANI:For instance, we can do lens on polio. We can do lens on malaria.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:In the distressed Otumara neighborhood, Alaja Jatto is also thinking beyond Ebola.

MAN:Well, she says she has something to tell the government, that they don’t have piped water, that their roads are bad, and that they need development.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Whether the government delivers on those improvements is unclear. But the Ebola campaign will continue and on high alert. That’s even though the number of contacts being tracked is now down to about 300. Each day, more people cross the critical 21 days since their exposure to the virus, the window in which symptoms can occur.Ironically, this success is a worry. Dr. Faisal Shuaib fears Nigeria could attract Ebola patients from nearby countries like Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea.

DR. FAISAL SHUAIB:We have had record levels of people surviving Ebola virus disease. And they might start feeling, well, maybe this is the place to come.

Reporting and Prevention

The Ebola virus has so far killed more than 2,800 people in West Africa, with the majority of deaths in Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone. But nearby Nigeria has been able to spread its message about the disease — what it is, where to report it, how to prevent it — with more success. Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports from Lagos.

Related Links:Reporters Notebook: Covering Ebola in Nigeria while navigating corruption.

Stigma surrounding sickness

Early detection has helped the survival rate in Nigeria. Fewer than half the cases have resulted in death. But the stigma only worsens the public health threat, says Dr. Ndadilnasiya Waziri, who heads the contact tracing effort.