- GWEN IFILL:Finally tonight, we take a look at one South American city that’s gone from being one of the world’s most dangerous places to an urban success story.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro has our report from Medellin, Colombia. It’s part of our series Agents for Change.

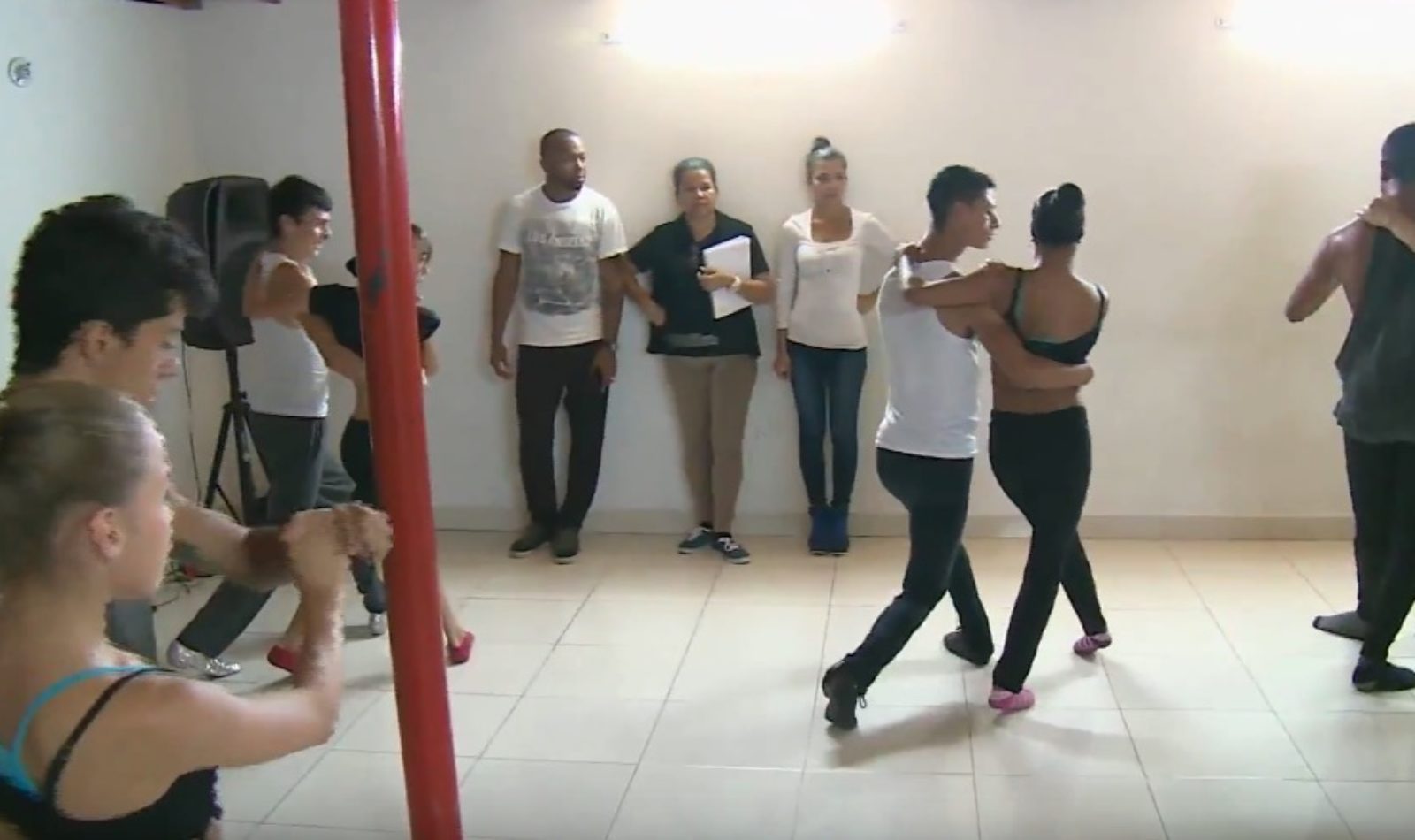

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:For two decades, Martha Alvarez has held dance classes year-round seven days a week. For the 350-odd students who cram into her tiny studios, it’s an alternative, she says, in a city that offers few.

- MARTHA ALVAREZ, Dance Instructor (through interpreter):I started this is 1992 out of concern for the amount of drug use and prostitution in the neighborhood.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:That was back when Medellin had become the world’s murder capital, the cocaine capital, home of the drug lord Pablo Escobar, who was killed by police in 1993.

- MARTHA ALVAREZ (through interpreter):It has changed a lot since then in terms of drug use, and the armed conflict has certainly diminished.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Medellin has seen a dramatic drop in violence. The murder rate is down from about 380 per 100,000 people to about 50. Experts credit a general calming trend in the country’s long-running civil war, also the efforts of new political leadership to bring people together in the city, says Alejandro Echeverri.

- ALEJANDRO ECHEVERRI, Architect (through interpreter):When we look at the narco-trafficking years of Pablo Escobar, people didn’t trust each other. They built barriers around themselves and they put walls up. So public space in this city takes on a far greater significance than anywhere else, because people didn’t look each other in the eye when they walked down the street.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Echeverri is an architect. He was part of the administration a decade ago that set out to create safe public spaces.We spoke in front of the Exploratorium he designed, a science museum that’s one of several distinctive new buildings.

- ALEJANDRO ECHEVERRI (through interpreter):This project right here is part of a broader narrative of social urbanism that the city started in 2003 and 2004. This place is symbolic because it connects the north of the city, which has a lot of poor neighborhoods and has traditionally been stigmatized, with the south. It’s not just the Exploratorium. It’s also the botanical gardens and the metro.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:The metro is perhaps the most extraordinary of all the building projects here, with a system of escalators and gondolas you typically see at ski resorts. Here, they reach into the poorest neighborhoods. These barrios cling to the mountains that surround the city, an almost vertical hike that was a barrier that excluded the poor, Echeverri says.

- ALEJANDRO ECHEVERRI (through interpreter):All of these policies are geared towards trying to decrease inequality and include the poor and marginalized sectors, who today can now access transportation and other services.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Along the new transit routes are community centers, libraries where there’s everything from computer and Internet stations to loan programs for would-be entrepreneurs, like Fernando Posada.He was among winners in a city- run contest. He won money to buy the kitchen equipment to expand a business he runs out of his home. Today, Posada is expanding from two to four employees. His cookies and waffle chips look like professional products, he proudly says, and they are selling well.

- FERNANDO POSADA, Entrepreneur (through interpreter):Since I got training, I have been able to professionalize and mechanize our production to meet all the labeling requirements, so that we can sell in more stores.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:The money for all this come from and unlikely source for a city.One of the biggest drivers of Medellin’s transformation is a company headquartered here called EPM. It’s one of Latin America’s most profitable electric utilities. This company is wholly owned by the city, but it’s run independently and privately. It pays taxes to the city, but it also sends it profits to the city. And last year, those amounted to nearly $600 million.EPM has expanded into six Latin American countries and seen record profits in recent years. The construction it’s fueled here has won Medellin international awards, says urban affairs scholar Catalina Ortiz. But, she adds, its not the whole story.CATALINA ORTIZ ARCINIEGAS, National University of Colombia, Medellin: Don’t be fooled by — by the great marketing that has been done. Scratch a little bit more and you are going to find several things that usually are not really unveiled.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Not unveiled, she says, is a huge housing challenge. The city has seen an influx of hundreds of thousands of rural residents displaced in Colombia’s long-running conflict.

- CATALINA ORTIZ ARCINIEGAS:Housing to re-house the households that are located in risky areas, or try to break the segregation pattern, and try to have more mixed-income housing, for instance. And that is a very big part of the problem, because, if you are dealing with informality, you really need to think in terms of alternative ways of tenure, of land tenure.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Many newcomers are in informal settlements, ever higher up the mountains. Ortiz says they’re vulnerable to poor services, possible landslides and also extortion by criminal gangs that still have a major presence.Architect Echeverri agrees there’s still much to do in a city where crime, though lower, is sill high, by corruption, a city whose historic industries like textiles have gone away.

- ALEJANDRO ECHEVERRI (through interpreter):There still remains a profound level of inequality here and a lot of economic policies that exclude the poor, a lot of it due to globalization. I’m also concerned about politics. Things are very fragile and could change very quickly. But I’m optimistic because Medellin does have this spirit of social commitment and trust.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:That optimism is also new, despite the challenges and complaints. Martha Alvarez says her neighborhood hasn’t seen a lot of new investment. It still lacks community meeting spaces, she says.

- MARTHA ALVAREZ (through interpreter):I would like the expand this space, because we could get 500 kids to attend every day.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Still, Alvarez says, her own business thriving, tiny tots to seasoned performers. Just the week before we visited, she told us, four of her senior students took jobs teaching dance in China, helping in their own way to make Medellin famous for a more wholesome kind of export.Fred de Sam Lazaro for “PBS NewsHour” in Medellin, Colombia.

- GWEN IFILL:A version of this story will air on the PBS program “Religion & Ethics Newsweekly.” Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota.

An Urban Success

A look at one South American city that’s gone from being one of the world’s most dangerous places to an urban success story.

Once the murder capital of the world, Medellin has seen a dramatic drop in violence.

From about 380 per 100,000 people to about 50.

Transforming a City

An effort to create safe public spaces and support policies geared towards trying to decrease inequality and include the poor and marginalized sectors has made a tremendous difference in Medellin

There’s still work to be done

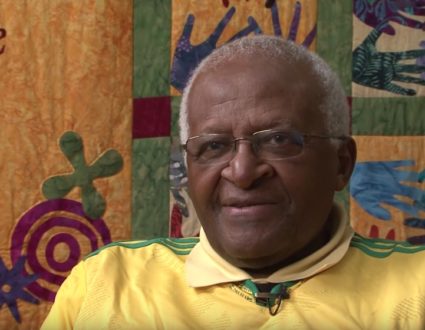

ALEJANDRO ECHEVERRI

Architect

“There still remains a profound level of inequality here and a lot of economic policies that exclude the poor, a lot of it due to globalization. I’m also concerned about politics. Things are very fragile and could change very quickly. But I’m optimistic because Medellin does have this spirit of social commitment and trust.”