- GWEN IFILL: Now: innovation in India, where there’s a new effort under way to bring mobility and prosthetic limbs to some of the world’s poorest people. Fred de Sam Lazaro reports, as part of our series on Breakthroughs.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Jaipur is one of India’s top tourist destinations, but not far from its architectural landmarks is a far more modest one that draws a whole different kind of visitor. They come — literally — on hands and knees to an organization commonly known as Jaipur Foot.

- DEVENDRA RAJ MEHTA: Now every year we are fitting anything between 23 to 25,000 limbs.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO: D.R. Mehta began offering artificial limbs and other services to physically disabled people nearly 40 years ago. About 150 patients arrive each day from across India, desperate people like Zareena, a widow who said she is reduced to panhandling to support her two children.

- DEVENDRA RAJ MEHTA: Bombay? She has come near — a place near Bombay. It’s about 100 kilometers. She has come to get a hand-pedaled tricycle.

- ZAREENA, India (through interpreter): You are the answer to my prayers.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO: She’s one of at least 5.5 million people in India with so-called locomotor disabilities — caused in her case by childhood polio. Others suffer congenital conditions. But, by far, the most frequent customers are amputees, trauma victims, mainly from road accidents. The Jaipur Foot organization was started with the help of government grants and is now funded mostly by foundations and individual donors. Its cost structure, for a lower limb, say, are minuscule by Western standards.

- DEVENDRA RAJ MEHTA: Now it’s $50.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Here’s a comparison. In the United States, a prosthesis like this would typically range in price from $8,000 to $12,000. It would be made of metal, aluminum, possibly carbon fiber, whereas, in Jaipur, the key ingredient is a PVC piping more commonly used to irrigate farms. And this is the key to a $50 artificial leg. Despite the overall success with artificial limbs, one challenge that has required a lot more innovation is the knee. DR. POOJA MUKUL, Orthopedic specialist: So much so that it’s better to lose both the limbs below the knee than to lose one leg above the knee. And the knee has been the weakest link in prosthetic componentry in the developing world. We’ve had very simple knee joints which are single axis, which are more like door hinges, and we’ve been using them largely because of the simplicity, low cost and also non-availability of any other options.

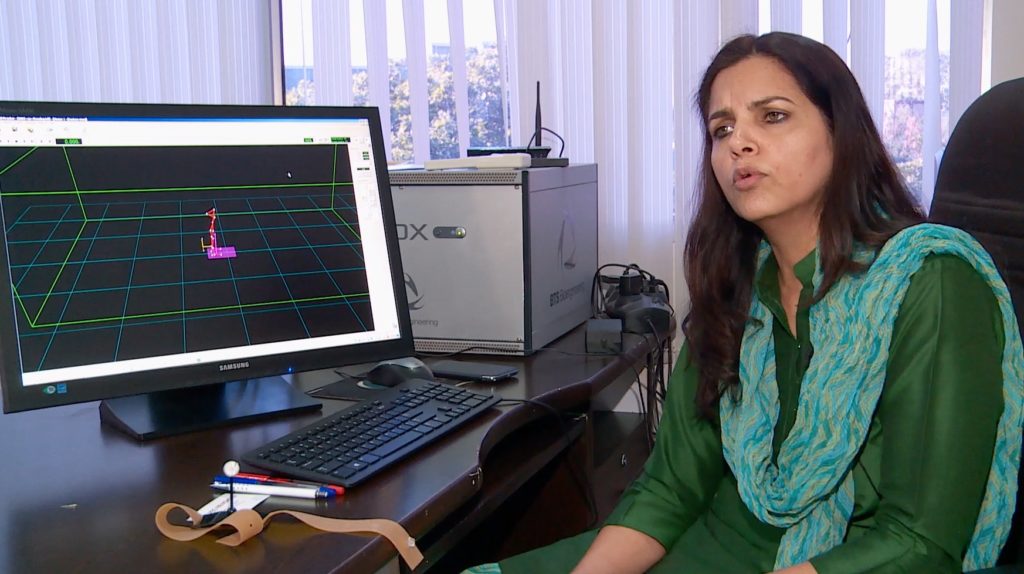

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Dr Pooja Mukul, an orthopedic specialist, is leading the effort to develop better options, partnering with MIT and Stanford University, with software typically used in the movies. They have conducted so-called gait analysis.

- DR. POOJA MUKUL: So this is the first prototype or version one of the polycentric knee that we developed in collaboration with Stanford.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Trials over the past five years with hundreds of patients in India and several other developing nations helped refine the new Jaipur knee, removing, for example, a clicking sound from version one.

- DR. POOJA MUKUL: Our patients don’t want to hear clicks. And they don’t want to be labeled as disabled. They don’t want a sound preceding their entry into an area. So then we got a bumper put in here, and now it’s a silent knee. And, also, the geometry — you see, this is very, very squarish, and doesn’t match the human geometry in any way. This one like — more like a knee.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO: It’s built to be especially sturdy and simple and especially for conditions in the developing world, where the typical amputee has a very different profile than in the West.

- DR. POOJA MUKUL: A typical amputee in India or the developing world would be post-traumatic, and age would be 20 to 30, in fact even younger, because if you’re looking at land mines, then a lot of young children were stepping on land mines and losing their limbs. So it’s a very young population who have no other medical condition pulling them down, except the fact that they unfortunately met with an accident. And they have their whole productive lives ahead of them, unlike in the West who’ve lost it because of diabetes or vascular insufficiency, they have cardiac issues, pulmonary issues, they’re mostly sedentary. So the demands that our patients put on prosthesis are very, very challenging.

- FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The new Jaipur knee will be ready for mass production later this year. Once the molds are made, the cost and manufacturing should come down to about $20 a piece, based on the simple low-cost approach for al prostheses here. They are cut and trimmed by hand. About a third of the workers here have Jaipur limbs themselves. Mehta says restoring people’s mobility makes a huge difference in lives, which he asked these amputees to show us by sprinting. This is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Jaipur, India, for the PBS NewsHour.

- GWEN IFILL: A version of this story aired on the PBS program “Religion & Ethics Newsweekly.” Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota.

A $20 Prosthetic Knee

In Jaipur, India, about 150 patients show up every day at an organization that creates low-cost prosthetic limbs for people with mobility problems. Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports on an innovative and affordable design being developed for those who have lost legs above the knee.

Related Links: Jaipur Foot

Every year Jaipur fits anything between 23,000 to 25,000 limbs

About a third of the workers here have Jaipur limbs themselves.

At least 5.5 million people in India have locomotor disabilities

By far, the most frequent customers are amputees, trauma victims, mainly from road accidents.

DR. POOJA MUKUL

“A typical amputee in India or the developing world would be post-traumatic, and age would be 20 to 30, in fact even younger, because if you’re looking at land mines, then a lot of young children were stepping on land mines and losing their limbs. So it’s a very young population who have no other medical condition pulling them down, except the fact that they unfortunately met with an accident. And they have their whole productive lives ahead of them”