GWEN IFILL:Now to Minnesota, where one part old technology, and several new ideas from retired workers, are creating a recipe of hope for many in the developing world.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro has the latest story in our Breakthroughs series on innovation and invention.

WOMAN:I promise you a perfect cake every time you bake. That’s right, perfect. You be the judge. Or write General Mills, Minneapolis, Minnesota, and get your money back.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Minnesota is where the idea of making things easier in the kitchen became an industry, the birthplace of such fictional legends as the Pillsbury Doughboy, the Jolly Green Giant and Betty Crocker.

WOMAN:A perfect cake every time you bake, cake after cake after cake.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Perfect? Maybe not. But convenient and efficient? No question.

ERV LENTZ, Volunteer:Some with nuts, some without.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:And that’s the idea behind a nonprofit company in Saint Paul called CTI, or Compatible Technology International. Different kind of cakes, though.

ERV LENTZ:Just plain trash.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Erv Lentz is squeezing discarded peanut shells, trying to make fuel briquettes. He’s 83, one of dozens of retired engineers, agronomists and other with ties to the food business who volunteer here.They’re now working on conveniences for a very different kitchen and customer, millions of mostly women in developing nations who toil for hours to provide food or to collect water for their families.

VERN CARDWELL, Volunteer:If you want to do the cranking there, get her up to speed.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Seventy-eight-year-old Vern Cardwell is working on a hand-cranked thresher that could save hours of labor and extract grain far more efficiently than the manual methods used now.

VERN CARDWELL:We’re obviously stripping all of the florets off that contain the grain.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:This test was on stocks of pearl millet, a staple in parts of Africa.

ERV LENTZ:Just blows your mind when you think how overnight, we can, for instance, help their useful pearl millet from 30 to 35 percent to darn near 90. The impact here is endless in terms of the impact on people.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:At least in theory. Over the years, they have learned hard lessons about the reality in a Minnesota lab and that in a village in, say, Malawi or Tanzania.Steve Clarke says they went to try out one invention in those African nations.

STEVE CLARKE, Volunteer:We had this great tool here called the grinder, which we knew could grind peanuts into peanut butter very, very well. But when we got over to those countries, we found out they didn’t make a lot of peanut butter.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:What they needed was a peanut sheller. Diet, social traditions and general all play a role in how a product is received, says CTI’s director, Alexandra Spieldoch.

ALEXANDRA SPIELDOCH, Director, Compatible Technology International:Tools that are designed in a void are largely not going to be adopted. The whole process of design needs to be about really understanding the context.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:One device they have had some success with is a water chlorinator. Unlike those used in rich countries, this one uses no electricity or pumps.Wesley Meier is one of few paid staffers at CTI. He heads this program in Nicaragua.

WESLEY MEIER, Compatible Technology International:Simple device, designed by an engineer based out of Saint Paul. So this is just the container for the tablet. This is the actual chlorine tablet. There’s five of them in here.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Dozens have been installed in remote mountainous communities in this Central American nation.The water supply in this area is mostly driven by gravity. It comes from natural streams up the mountain and flows by gravity into tanks like this one. The tiny community of Las Animas is having a CTI chlorinator installed. When it’s done, the 380 residents of the village will have safe water at almost no additional cost.The device costs just $150. Its plastic pipes and chlorine tablets are available locally.

MAN (through interpreter):At this point, the water passes through the chlorine tablet and mixes with the water. As it mixes, it eats up the bacteria and cleans the water.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Community leaders like Emili Juarez are instructed to monitor chlorine levels and to change the tablets periodically.

EMILI JUAREZ (through interpreter):We really didn’t have potable water, and we really needed to install this system. We know that unclean water can lead to diseases like diarrhea and hepatitis.

ERV LENTZ:When we go to play bridge at the club, people will often times come along and, it’s about once a month, the thing, and, “Well, how’s the water system doing?” And I usually put a little needle in and say, well, we could do a lot better if we had a little more money, you know.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Does that end the conversation there?

ERV LENTZ:No.(LAUGHTER)

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:CTI’s annual budget is $750,000, mostly from charitable donations. But that doesn’t include thousands of hours volunteers like Erv Lentz put in pursuing the perfect pedal-powered potato slicer, grinder or pepper shredder.Vern Cardwell did manage to come up with a peanut sheller and got to see it demonstrated in Malawi.

VERN CARDWELL:By hand they can get two pounds of nuts shelled an hour, and with our disc peanut sheller we can do 50 to 60 pounds of nuts an hour.And the women look at that, and they’re just giggling, and they’re all excited about this piece of equipment, and everybody wants — you’ll leave it here? You’ll leave it here, so we can use it?And that kind of excitement is very infectious.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:It’s what’s kept him and the other coming here almost full time for years.This is Fred de Sam Lazaro for the PBS NewsHour in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

GWEN IFILL:A version of this story aired on the PBS program “Religion & Ethics Newsweekly.”Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota.

Related Links:Compatible Technology International

Worlds Apart

Kitchen convenience means something different for millions of small farmers in poor countries. A nonprofit in St. Paul creates simple, efficient tools that could save people hours of labor on tasks like threshing grain and shelling peanuts. Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports.

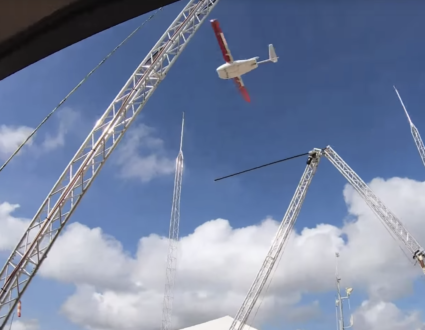

Safe water for $150

Dozens of water chlorinators like the one on the left have been installed in remote mountainous communities in Nicaragua.