GWEN IFILL: Next to Pakistan.

We look at one effort to tackle a widespread public health problem that gets scant attention. It’s part of our Agents for Change series.

Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports from Karachi.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: For decades, Pakistan has been in a state of post-traumatic stress, from the Afghan war, ethnic tension, religious violence, terrorism.

The economy, hindered by corruption, does little to reduce the poverty that drives so much of the turmoil. It’s enough to drive anyone crazy.

And psychiatrist Saadia Quraishy, with the Pakistan-based Aman Foundation, says that’s exactly what it does to a lot of people.

DR. SAADIA QURAISHY, Psychiatrist: About 40 percent of the population suffers from common mental disorders.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Four-zero?

SAADIA QURAISHY: Yes. And some informal reports suggest even higher.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Fifty-seven-year-old shopkeeper Anwar Kaskeli presents a classic case

ANWR KASKELI, Pakistan (through translator): I wrote in the newspapers for years about why are the basic necessities of life not being provided to people here, like water, roads, schools, especially education?

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Between those worries and a growing inability to make ends meet, he says he simply withdrew.

ANWAR KASKELI (through translator): For 10 years, I couldn’t sit for more than 10 minutes. My mood was just down. My joints would hurt. That made the depression worse. This went on for 10 years.

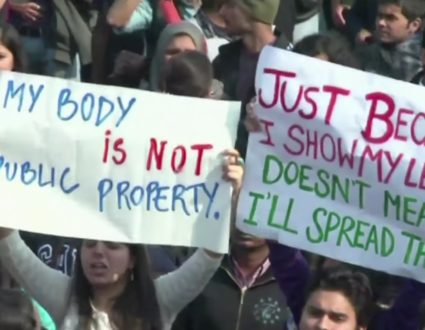

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Throughout South Asia, mental illness goes unreported, undiagnosed, and untreated. It’s socially taboo, often viewed as a curse from God, not an illness.

Patients have often been restrained in chains and subjected to other humiliation, says Dr. Quraishy.

DR. SAADIA QURAISHY: It’s very difficult to express mental health symptoms to — not only to the clinicians or professionals, but even to yourself and to the families. There’s such a stigma related to that. But it’s much more acceptable to say you have a headache or a stomach ache or a backache, for which you can be taken out to get help.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Not that much help is available. Very few Pakistani doctors are trained to diagnose psychiatric disorders, whether acute ones like schizophrenia or common ones like depression.

This is a country of 200 million people. For all of them, there are perhaps 500 practicing psychiatrists. In all likelihood, there are more psychiatrists of Pakistani origin working in the United States and great Britain than there are in all of Pakistan.

CHRIS UNDERHILL, Founder, BasicNeeds: Generally, in the developing world, in the poor world, you’re talking about 1.5 million people per psychiatrist.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: What is it here in Britain or in the United States?

CHRIS UNDERHILL: Oh, it’s about one per 10,000.

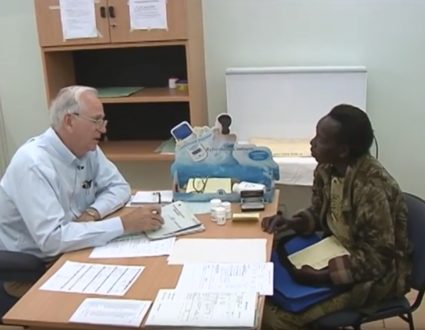

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Chris Underhill is the founder of a British-based aid group called BasicNeeds, which tries to deliver mental health care despite the challenges. Partnering with local nonprofits, it began running clinics here two years ago, no fancy couches here, just a temporary one-room, one-doc psychiatric ward.

DR. SALIM AHMED, Psychiatrist (through translator): Do you get angry a lot?

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: On this recent morning, Dr. Salim Ahmed swiftly dispatched patients, most in follow-up visits. Their prescriptions were refilled a few feet away. Some patients were sent to counseling behind the curtain in the corner.

DR. SALIM AHMED: The team, the community-based workers, they are making sure that they are taking their medications on a regular basis. If suppose they have some problems like some side effects of the drugs, those community-based workers, they communicate with us.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The team he works with is mainly drawn from the local community.

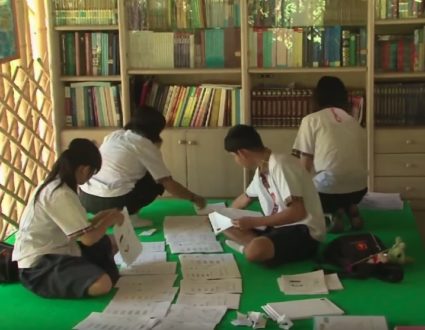

With role playing and skits, ordinary citizens are trained as outreach workers to follow up on patients, to look for symptoms or side effects and to refer patients back when clinics are held.

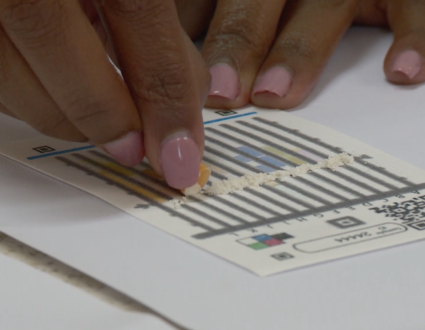

Families dealing with mental illness are brought together. They get training in skills, like sewing, which may earn some income and reduce stress. In Pakistan, the program has already served 12,000 people. The holistic approach, generic drugs and community-based care, has a longer track record in other countries, Underhill says, and it’s inexpensive, about $20 to $30 per person for year.

CHRIS UNDERHILL: Not just the medication and all of that, but also the rest of our model, which includes an element of encouraging and training people back into livelihood.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Along with antidepressant meds, Anwar Kaskeli received a micro-loan from the BasicNeeds program to reopen his tiny store.

ANWAR KASKELI (through translator): All I want is enough for three meals a day. I don’t want any riches, anything.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Business isn’t great, and his recovery is still precarious. It might be a metaphor for mental health care in poor countries. It’s been a challenge to scale up, because it just doesn’t seem as pressing to governments as other issues, says Underhill, even though it exacts a huge toll.

CHRIS UNDERHILL: Literally, last year, $2.5 trillion came out of the global economy because of mental ill health. Now, bringing that down to the level of policy-makers in one country, Pakistan, isn’t easy.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: He has a similar challenge with many Western donors, on whom BasicNeeds relies heavily for support.

CHRIS UNDERHILL: If you take one of the big cities in the United States, and you think about the number of people who have mental illness on the streets, I talk to them about the developing world, and they say, but it’s right on our streets.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Despite the presence of mentally ill people on U.S. streets, Underhill says the harsh reality is that about three-fourths of the 450 million people with mental illness worldwide are in developing countries, and three-fourths of them are untreated.

In Pakistan’s Sindh Province, I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro for the “PBS NewsHour.”

JUDY WOODRUFF: Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota.

FIGHTING A STIGMA

Although nearly half of the population could have mental health issues, getting help isn’t easy in Pakistan. The stigma against mental illness is prevalent, and even for those who do want to get help, psychiatrists are in short supply. As part of our “Agents For Change” series, Fred de Sam Lazaro looks at the efforts being made to change this situation.

Related Links:BasicNeeds

A Holistic Approach

Using generic drugs and community-based care, one approach brings together families dealing with mental illness and provides training in skills, like sewing, which may earn some income and reduce stress..