FRED DE SAM LAZARO, correspondent: There was a time when this ballad could only be performed clandestinely in Nicaragua and even neighboring countries. It was part of a Mass banned by Church leaders and frowned on by government authorities. In this traditional Catholic region, embroiled in one of the cold war’s last proxy battles, it’s not hard to see how it could be provocative. Christ is addressed as “comrade,” for example.

CARLOS MEJIA (Composer-Performer): All the words, the expressions used were used in everyday life. This Mass was so popular because it was transparent.

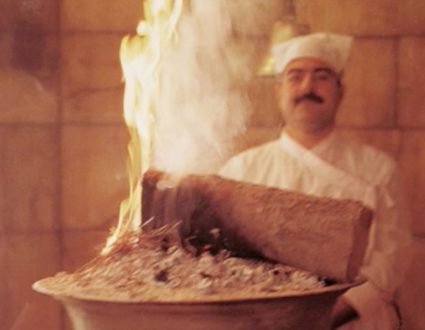

DE SAM LAZARO: Carlos Mejia wrote this Mass in 1975, dedicated to campesinas or peasant farmers. He still performs selections from it in his family’s restaurant in Nicaragua’s capital, Managua.

post01-liberation-theology

MEJIA: This Campesina Mass was a departure from the traditional Mass, where you would be seated in the church and the faithful, they look up to God, and they pray, “God have pity on us.” And we started having people say, “God show solidarity with us.” There was no longer that distance. This was a new concept.

DE SAM LAZARO: Mejia was part of a movement across Latin America that became known as liberation theology. Its proponents pledged to work for the poor against what they saw as an oppressive ruling class. It was inspired by the Second Vatican Council, the historic gathering called in 1962 by Pope John XXIII to bring the Church closer to the faithful.

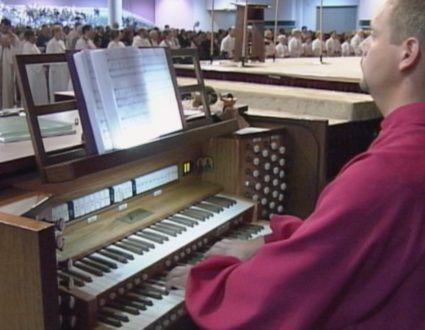

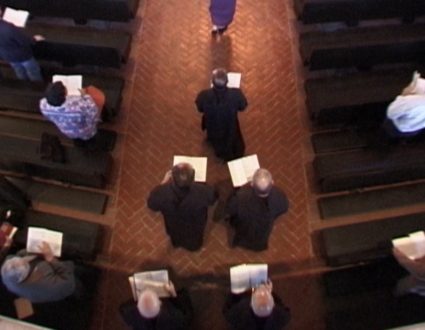

Among Vatican II’s most symbolic changes: priests who historically faced the altar began facing the congregation. And the liturgy, celebrated for centuries in Latin, was simplified. It’s now conducted in the local language.

REV. MIGUEL D’ESCOTO BROCKMANN: Pope John XXIII felt that things were stagnated in the Church—that we needed fresh air. He said we must open up the windows and let fresh air come into our Church to revitalize it.

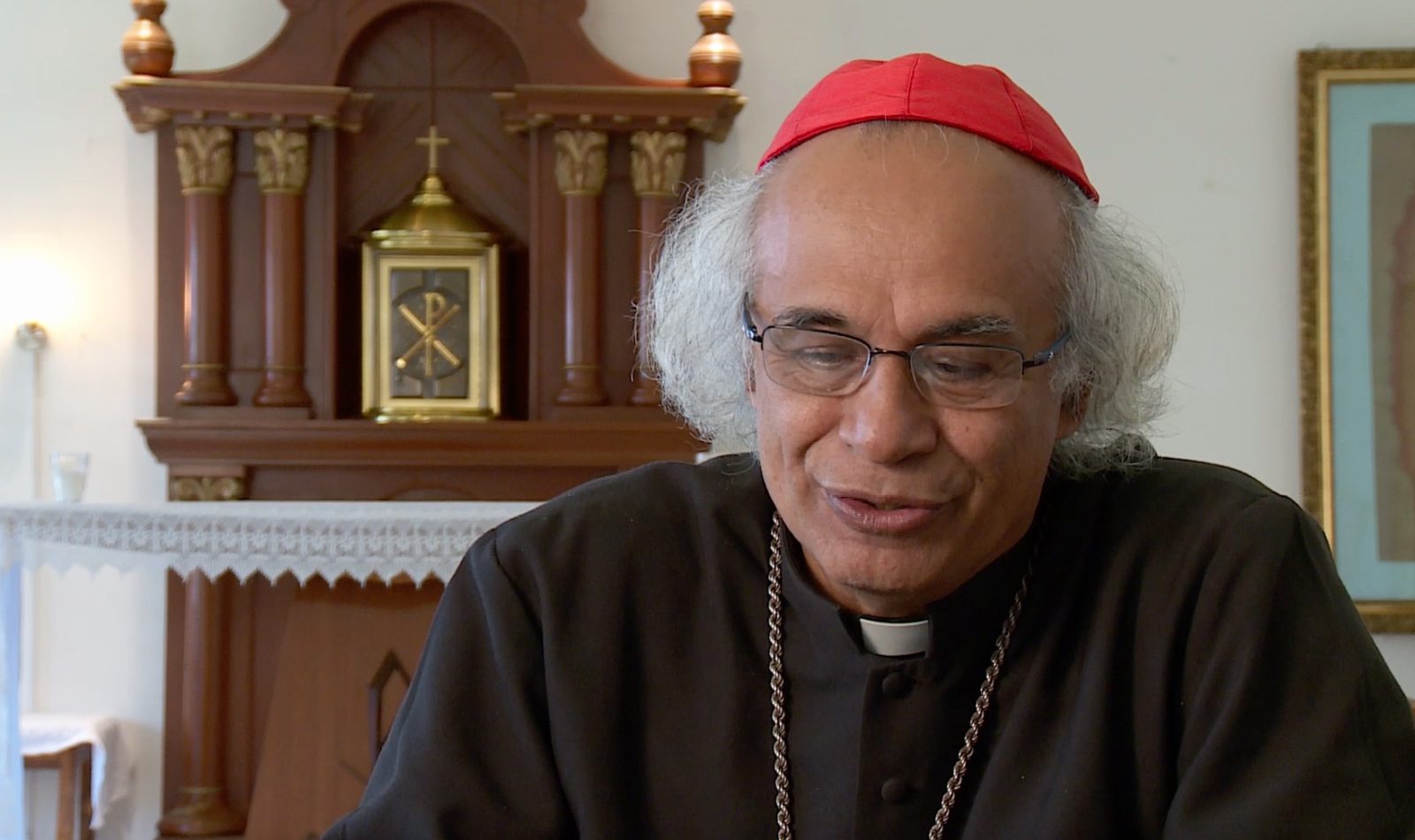

DE SAM LAZARO: Father Miguel D’Escoto Brockmann, a priest from the Maryknoll Order, brought his belief in liberation theology to the context of Nicaragua’s politics and its civil war. He joined the leftist Sandinista government that overthrew the right-wing dictatorship in 1979. He became Nicaragua’s foreign minister.

D’ESCOTO: The message of Jesus was 100 percent political. That’s why he’s not only anti-imperialist, he’s revolutionary.

DE SAM LAZARO: Representing a Soviet-backed government fighting a civil war against the U.S.-backed Contra rebels, Brockmann was a strident critic of what he called U.S. imperialism. But his work ran afoul of a directive from John Paul II that clergy not hold political office. In 1985, Brockmann was suspended from the priesthood for defying the order. He remains unapologetic.

D’ESCOTO: I have to obey, but God first. That’s what you call the primacy of conscience. And Vatican II clearly establishes the primacy of conscience again. But John Paul II had a pre-Vatican II mentality. It’s not his fault. He was Polish, and Poland was the Catholic country where the ideas of Vatican II least penetrated, and besides that, he was extremely anti-Communist.

DE SAM LAZARO: Is it not true that communism and the ideals of socialism were very perverted in countries like Poland especially, and that that might have really affected his thinking?

Miguel D’Escoto Brockmann

D’ESCOTO: Correct, that’s true.

DE SAM LAZARO: Brockmann, who is 83 now, appealed his suspension to Pope Francis, saying he wanted to say Mass once more before he dies. The petition was approved by a Vatican that he says is being transformed.

D’ESCOTO: The Church is more attuned to Jesus. That’s the only thing that matters.

DE SAM LAZARO: Under Francis, you mean?

D’ESCOTO: Under Francis, yes.

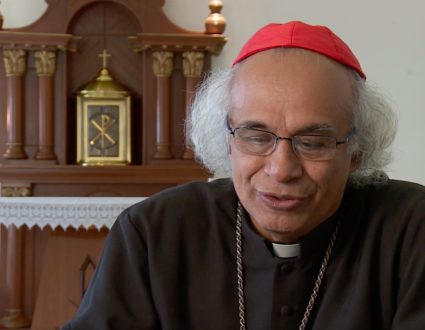

DE SAM LAZARO: Another signal Brockmann and others point to is the pope’s decision to open the way to beatify Oscar Romero, the archbishop in neighboring El Salvador, who was assassinated in 1980 while saying Mass. Romero was a critic of the growing social and economic disparities and political repression in the region. Many analysts think his beatification was delayed under Francis’s predecessors because of Romero’s perceived sympathy for the liberation theologians. But the archbishop of Managua, who was appointed by Pope Francis, doesn’t view these developments as an endorsement of the liberation theology dissidents.

ARCHBISHOP LEOPOLDO BRENES: It has to do with the pope being a Latin American. He’s well aware of the path of the Church across this region, and he knows the problems of Latin America.

DE SAM LAZARO: Archbishop Brenes rejects the allegations by liberation theology exponents that the Church has historically sided with the moneyed and powerful interests at the expense of the poor.

BRENES: That is a falsehood. The Church in Latin America and Nicaragua has always been serving and on the side of the poor. That’s why it is strong. Liberation theology never actually gained much momentum here because people here are very faithful and allied with the Church.

DE SAM LAZARO: Theology professor Michele Naglis has a different explanation.

PROFESSOR MICHELE NAGLIS: The search for God is a very personal pursuit.

DE SAM LAZARO: She says liberation theology was not a movement to explore individual and personal spirituality but rather a collective pursuit, mixing a political and religious agenda. It was a product of its time, she says.

NAGLIS: Liberation theology had a basis in Marxism, which was very necessary and relevant at the time. But in socio-political terms, there were a lot of factors that were ignored or excluded, such as the environment or gender issues, for example.

DE SAM LAZARO: There may be disagreement on whether or not the new pope has affirmed their long-ago efforts. But the aging proponents of liberation theology say their ideals are far more closely aligned with the pope today—for the first time in a generation.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Managua, Nicaragua.

A New Era

With its link between protecting the Earth and helping the poor, Pope Francis’s encyclical recalls the era of the liberation theology movement in the Catholic Church. It was a controversial effort begun in Latin America in the 1960s-1980s to side with the poor and oppressed over the rich and the powerful and to promote social justice and transformation. Correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro spoke with some of the aging veterans of Nicaragua’s liberation theology struggles of a generation ago.

“The message of Jesus was 100% political. That’s why he’s not only anti-imperialist, he’s revolutionary.”