Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports from Karachi, Pakistan, part of his series Agents for Change.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Eleven-year-old Aqsa has high ambitions.

GIRL: First, I want to be a public speaker, and then president of Pakistan to change.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: To change things?

How do you harness the energy and the enthusiasm of young children?

If you became president of Pakistan, what would you like to do?

GIRL: First, I will clean the litter, because the biggest problem is litter.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: In Lyari, one of Karachi’s toughest neighborhoods, Aqsa is part of an experiment started six years ago called the Kiran School. The children here are encouraged to think big, to use their imaginations. But the gritty reality just outside of a city often racked by terrorism and violence looms large.

GIRL: There are many people who are like, they are heartless, so they kill people.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: What kind of terrorism do you see in Lyari?

GIRL: They killed one man at night. It was late, 2:00. They came and they killed and went.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Eleven-year-old Hammad also has witnessed killing first hand. He wants to be a robotics scientist when he grows up.

BOY: Robots, like, do everything. And they will stop terrorism, not kill them, but they will stop terrorism and just give to the police.

SABINA KHATRI, Founder, Kiran School: He said that, why can’t we have robots in Lyari as policemen?

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Sabina Khatri is the school founder.

SABINA KHATRI: Nobody can kill the robots. The bad people will be defeated.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: A mother of grown children, Khatri lived in Europe for many years before returning to Karachi. She started the Kiran School six years ago, based on the Montessori learning model, admitting just 20 students each year, the goal, prepare them to attend top private English-language schools, alongside children from Karachi’s tiny upper class.

She’s raised scholarships and donations in a foundation for her social enterprise. The children have thrived, Khatri says, even become Harvard material.

SABINA KHATRI: And this is one of the principals who told me that this kid can make it to Harvard.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Problem is, the vast majority of children in Lyari and Pakistan will go nowhere. Just 2 percent of the government’s budget goes to education, and much of that is squandered. Public schools are in decrepit condition. Fifty percent lack electricity; 40 percent have no toilets. Many are stripped of furniture. And it gets worse.

It’s not uncommon in this country for there to be public schools that exist only on paper. The money’s been allocated, but no building’s been built, no students enrolled. The only thing that is up and running is the payroll for so-called teachers. They are, in fact, mostly beneficiaries of political favors.

Khatri says the government is starting to face facts, and it’s invited outsiders to take over failing schools. A few months ago, Khatri adopted this Lyari middle school. Her first task was to hire new teachers and tell most of the old ones, tenured, so they could not be fired, to just stay away.

SABINA KHATRI: They come and make — create troubles in the school.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: So, you would just as soon have them be…

SABINA KHATRI: Yes. I just tell them that, if you’re creating trouble here, it’s better that you don’t come.

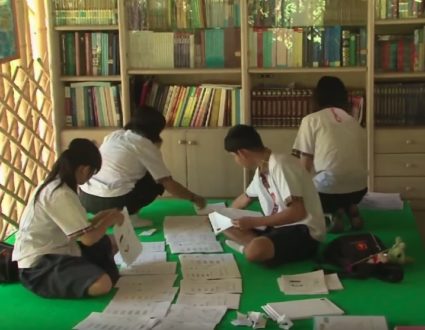

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Her next step, rearrange classes to cluster students by ability, not grade level.

SABINA KHATRI: Although they do say that they are in the eighth grade or ninth grade, they can’t even — they don’t even know how to write their name in Urdu, let alone in English.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The students here have been put in an intense remedial curriculum.

There’s strong emphasis on inquiry and critical thinking, instead of the more common rote learning. The school also teaches Islamic values that Khatri says are too often neglected, like tolerance. It’s a challenge in a conservative and in many ways isolated society.

SABINA KHATRI: The biggest criticism and concern was that maybe we were very modern, that they feel that we teach our children music and dance and we are making them broad-minded.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: And she’s poised to take a controversial step.

SABINA KHATRI: We have actually taken permission for a co-education school. So, we want to admit girls now, because we already have 250 boys in school.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Regular meetings with parents and the community are also part of the job. When one woman at a recent open house worried the school was teaching liberal values, Khatri asked an 11-year-old from the Kiran School to respond.

SABINA KHATRI: She actually said that, you know, we believe in God. The way we have learned about God is, God is love. But that is not the way other children are taught. It’s always taught that God will punish you. God loves you.

They were quiet.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: And accepting?

SABINA KHATRI: It was a wonderful — yes, I think so, because, then, after that, the same lady, she said, I want an admission form.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: One parent was assuaged, but Khatri says intolerance remains a threat. So, community service projects are another way to win the neighborhood over. But in a country racked by instability, there is no guarantee.

SABINA KHATRI: Anything can happen to me any time, especially in the situation I am, and especially the kind of things that have been happening in our country, because social workers have been targeted lately, in the past two or three years. Anyone who’s trying to help out people, they just kill them.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Still, Khatri, who was recently joined by a prominent business leader, plans to persist with what she calls a promising prototype to fix a broken school system.

She and many others say it’s where intolerance and most of Pakistan’s social and economic problems have their root.

I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro for the PBS NewsHour in Karachi, Pakistan.

JUDY WOODRUFF: Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota.

An Alternative School System

In Pakistan, education could help change the fortunes of impoverished families, but corruption and pressure by the Taliban prevent many children from enrolling. An alternative school system is making efforts to expand access and change attitudes towards education for impoverished boys and girls. Fred de Sam Lazaro reports.

Related Links

A New Model

At the Kiran school there’s strong emphasis on inquiry and critical thinking, instead of the more common rote learning. The school also teaches Islamic values that Khatri says are too often neglected, like tolerance.