GWEN IFILL:But, first, combating a growing diabetes epidemic in Mexico.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports. It’s part of his series Agents for Change.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:The North American Free Trade Agreement brought Mexico chain restaurants, malls and big box stores with abundant shelves, and an epidemic of diabetes.JAVIER LOZANO, Founder, Clinicas del Azucar: Regular food, but sugar free.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Javier Lozano, whose mother suffers from the disease, thinks he can make a difference. Three years ago, he opened a chain called Clinicas del Azucar, or the Sugar Clinics.

JAVIER LOZANO:Our dream was, imagine there’s a clinic in every corner. Just as we have franchise for hamburgers and pizza and fried chicken.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:The clinics are a one-stop shop to see a doctor or nutritionist, get your eyes checked, or feet, then pick up a pair of shoes or snacks.Lozano, a 33-year-old MIT graduate, hopes to have 200 outlets by 2020, but it’s a tiny fraction of the demand in a country that by then could have 20 million diabetics.

DR. SIMON BARQUERA, National Institute of Public Health: Basically, diabetes prevalence has been doubling every six to 10 years.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Dr. Simon Barquera of Mexico’s National Health Institute says it now affects 14 percent of Mexican adults, a population with widespread genetic predisposition to diabetes.Adding to the risk, 72 percent are obese or overweight. Those numbers are now higher than Mexico’s northern neighbors, but with double the impact. Far fewer Mexicans have their symptoms under control.

DR. SIMON BARQUERA:For example, in Canada and the U.S., more than half of the population with diabetes has adequate control, in Mexico, only 25 percent.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Complicating matters, half of those affected aren’t aware they have diabetes. And those who are diagnosed can remain asymptomatic for years, and they do little to control its advance.

DR. SIMON BARQUERA:They go looking for private care and they see that it’s too expensive. Then, usually, they go back to the public care, and it’s limited. So, you know, when people have a difficult decision, we usually just defer the decision.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Maria De La Luz Mireles says she struggled for years with scattered, substandard care until specialists at the Sugar Clinic helped bring her symptoms under control.

MARIA DE LA LUZ MIRELES, Diabetes patient (through interpreter): I went to many clinics and never got to see a specialist. It was general doctors and they’d change my medications. This went on for 20 years.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:That overall lack of access to care means more advanced cases: limb amputations, heart, kidney and eye disease, more people like Luis Martinez, at 64, long retired and nearly incapacitated.

LUIS MARTINEZ, Diabetes Patient (through interpreter):My kidneys have been very seriously affected, so I have to have dialysis twice a day, and four months ago, I lost the last bit of sight that I had.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:As a young man, Martinez moved from the country to the city, part of a massive urbanization. Three out of four people now inhabit cities in this once agrarian nation, says Sugar Clinics endocrinologist Eduardo Camacho.

DR. EDUARDO CAMACHO, Clinicas del Azucar (through interpreter): Most people lived in the countryside, and so they used a lot of energy and got a lot of exercise in order to feed themselves. It was labor-intensive work. Now, with urbanization, people are using much less energy in their daily lives to get the food that that they need.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Then there’s the food, plentiful, affordable, but processed. Dr. Barquera says it’s an industrialized version of the healthy, traditional Mexican diet.

EDUARDO CAMACHO:What we have now, tacos, both the tortillas, bigger. They have a lot of meat. They have a lot of fat. Sometimes, the quesadillas are deep-fried.

MAN (through interpreter):People are on the go, working, so if you have got money, you go to a restaurant. If you don’t, you eat tacos on the street. And people drink soda, rather than have water.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Maria Sanchez Perez, who is losing her sight and lives in fear of a stroke, blames her addiction to Coca-Cola.

MARIA SANCHEZ PEREZ, Diabetes patient (through interpreter): Those big bottles that you see, those wouldn’t even last me a day.

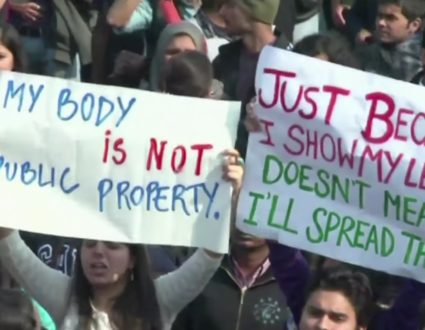

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:She’s hardly alone. According to Coca-Cola, Mexicans are far and away the biggest consumers of the company’s products, especially the flagship Coca-Cola, which is sold in three-liter bottles in this country. On average, the company says Mexicans consume 43 gallons of Coke products per year. That works out to about 55 of these per person per year.In 2014, after a campaign by citizen activist groups, Mexico became the first nation to enact a so-called soda tax, 10 percent on sugar-sweetened drinks, 8 percent on salty snacks. In its first year, one study showed consumption dropped by 6 percent. But the study’s methods were questioned by the food and beverage industry, led by multinationals including U.S.- based Coke and Pepsi.The industry has fought such tax proposals, successfully in most cases, including New York and San Francisco.

LORENA CERDAN, Food and Beverage Industry Spokesperson: It’s a regressive…

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:It’s a regressive tax, is what you’re saying.

LORENA CERDAN:It’s a regressive tax, yes.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Lorena Cerdan is a spokesperson for Mexico’s food and beverage trade group, which argues its products are unfairly singled out.There’s absolutely no link between soda consumption at 43 gallons per person per year and the disease burden of this country?

LORENA CERDAN (through interpreter):There is no causal relationship to link directly sugary drinks with diabetes. There is a causal relationship between a sedentary lifestyle and an overconsumption of calories.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:She says the urbanized lifestyle and overall increase in calories from many sources are the problem.The industry has contributed to public awareness and fitness campaigns. But its critics, like consumer advocate Alejandro Calvillo, are skeptical.

ALEJANDRO CALVILLO, Consumer advocate: They are, by this way, trying to create confusion, that you don’t have good products or bad products. Everything is on the relation of the calorie intake that you consume and the calories that you spend.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:He says there’s also been lackluster enforcement of recent regulations, banning salty snacks and sodas in schools, for example.

CAVUTO:All right. This is the schools in the country that we have reports that are not following the regulation. We are making a list of the schools.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:And experts say it’s not just at school, but at home that a culture shift is needed; 26-year-old Karla Almanza gets good grades from her nutritionist at the Sugar Clinics for controlling her weight and sugar levels. But she says its not been easy cutting out foods and sugary drinks she loves and imposing a diet on her mother, who is also diabetic, and two daughters and her husband, who are not.

KARLA ALMANZA, Diabetes Sufferer (through interpreter):For the children, I have always cooked like that. They’re used to it. It’s really difficult for my husband. He says: “I’m not a rabbit. Give me some more meat.”

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:It’s also hard on the budget, she says. The healthy diet, ironically, is costlier than fast food. Helping her budget, her clinic fees are fixed, payable up front for the full year, though financing is offered to help patients afford care.Lozano says this ensures patients come back regularly, their complications not only treated, but also tracked.

JAVIER LOZANO:We have been on the — more than three years in care and we have seen more than 15,000 patients. So we have a lot of data.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:The data helps determine what works and what doesn’t, which also in turn helps lower costs and increase access to care in an epidemic that most experts says this nation is unprepared for.For the PBS NewsHour, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Monterrey, Mexico.

GWEN IFILL:Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota.

A Country-Wide Problem

In Mexico, over 70 percent of citizens are overweight or obese and 14 percent of Mexican adults now suffer from diabetes, though half of those affected aren’t even aware they have the disease. Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports on the struggle to bring the disease under control.

Related Links:Clinicas del Azucar

“My kidneys have been very seriously affected, so I have to have dialysis twice a day, and four months ago, I lost the last bit of sight that I had.”

Treating and tracking diabetes

The Sugar Clinics have seen over 15,000 patients in three years and gathers data to improve care. Fees are fixed, payable up front for the full year and financing is offered to help patients afford care, which Lozano says this ensures patients come back regularly.