JUDY WOODRUFF: But first: how one for-profit school model is being tested to help revitalize a school system in West Africa.

Our story is in Liberia, a country founded by freed American slaves with a history marked by suffering, including two recent civil wars and the Ebola epidemic.

Today, the government is trying to rebuild a shattered nation, but a move to employ a for-profit American education company has drawn controversy.

Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports as part of our weekly education series on Making the Grade.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: It’s Friday morning, and the children at this public elementary school are singing patriotic songs that honor their country’s founding by freed American slaves.

And as the U.S.-inspired flag is being raised, so too are hopes about how public education can be quickly and dramatically improved. These students are part of a grand experiment to see if a private for-profit U.S.-based company can turn things around in a nation utterly destroyed by a 14-year long civil war and a recent battle with Ebola.

The president of Liberia has called the country’s education system a mess. What did she mean? Consider this statistic: In 2013, not one of 25,000 high school graduates in this country managed to pass the college entrance exam for the University of Liberia.

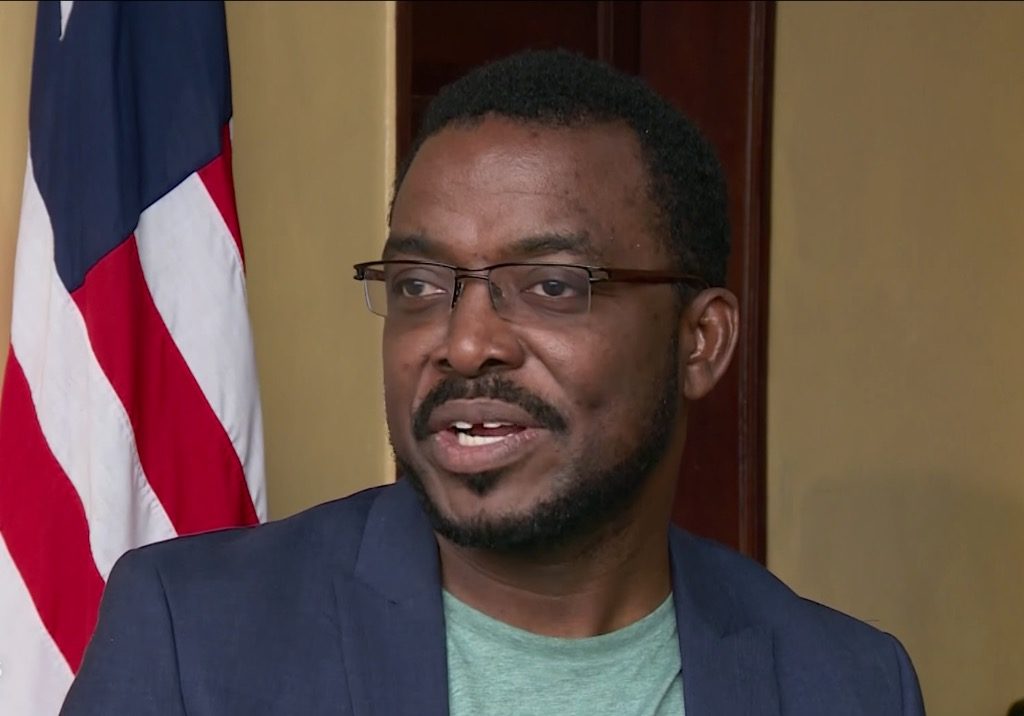

The experiment to bring in private partners was designed by Education Minister George Werner, who took office 15 months ago, hired by the president, he says, to act quickly.

GEORGE WERNER, Education Minister, Liberia: If we stayed the course, followed the traditional ways of doing things, we wouldn’t catch up with our neighboring counterparts.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Werner had been impressed during a visit to Kenya, where the U.S. company Bridge International Academies operates more than 350 private schools.

In Liberia, where average annual household income is less than $500, Werner knew most families could not afford the monthly $6 fee that Bridge charges per child in those other countries. But he had an idea.

GEORGE WERNER: What if we had a hybrid for public and private? There are certain things that the private sector does better than the public sector. Government can come up with the policies, but management systems and service delivery, often, the private sector does better than the government.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Werner hired seven private organizations to run a total of 94 primary schools. Bridge, the only for-profit, runs 24 of them.

Josh Nathan is the company’s academic director.

JOSH NATHAN, Academic Director, Bridge International Academies: What the government has done in Liberia is quite courageous. They’ve said, we’re struggling with providing children this basic right, so what we want to do is look around, look inside Liberia and outside Liberia, at other people who are succeeding in providing children with an excellent education.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The government agreed to pay the companies directly, so education remains free for families. The companies also provide uniforms, which are required at public schools and whose cost keeps many from attending. When we visited the Bridge school in Kendaja, the semester was only two weeks underway, and many of the uniforms had not yet arrived.

MAGDALENE BROWN, Principal, Bridge School, Kendaja: Today is a wonderful day for us too.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Principal Magdalene Brown said the improvements were already very apparent. For one thing, there’s a much longer school day. Last year, it was just four hours a day.

MAGDALENE BROWN: Bridge has us come to school much earlier, like we at 7:30, and then Bridge have us stay on until 3:30 every day. And that means the children will learn better.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Even the students seem to like it more, including 15-year-old Mercy Freeman.

MERCY FREEMAN, Teachers Union: We come to school on time. We sit in class.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: And school actually runs like a school?

MERCY FREEMAN: Yes.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: There are also new rules, such as no more corporal punishment. And along with new textbooks, every teacher is given a computer tablet and is required to stick to pre-loaded lesson plans.

Critics of this so-called school-in-a-box approach say it encourages robotic teaching and has allowed Bridge in other countries to hire cheaper, less qualified instructors. That’s less of an issue in Liberia, where Bridge schools retrain teachers who are already working in the school system and where many had their own education disrupted by the civil war.

In this building, teachers seemed grateful for the guidance.

Amos Jumanine has taught for seven years, but says he was a late bloomer.

AMOS JUMANINE, Teacher: I was 17 years when I started ABCs.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: You went to kindergarten learning your ABCs when you were 17?

AMOS JUMANINE: Yeah, 17.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: He is hopeful the new partnership will be good for the students. But he is adamant on one thing that needs to change: Teachers need to be paid more money, especially now that they’re required to work longer hours.

AMOS JUMANINE: I cannot afford to buy food for myself.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Financially, it’s very difficult?

AMOS JUMANINE: Yes, financially.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Very difficult.

AMOS JUMANINE: Very difficult.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Teachers in Liberia earn about $100 a month, and many say they take second jobs just to make ends meet. That contributes to one of the biggest problems in Liberian schools: chronic teacher absenteeism.

Not only are teachers routinely absent. Many really never existed, just their names on paychecks issued by the schools.

Education Minister Werner says he’s purged about 1,300 so-called ghost teachers, saving $2 million that was being siphoned away in fraud.

JOSH NATHAN: The president herself has acknowledged that this is a system that is really a mess.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Josh Nathan says the Bridge schools use software in the teachers’ tablets to track their daily attendance.

JOSH NATHAN: We think this is incredibly important to creating accountability and being able to watch every single day, where are our teachers, are they where they need to be?

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: For their part, the teachers union is strongly opposed to the partnership program. It points out that these new schools have smaller class size, around 45 to 55 pupils, and receive about $10 to $15 more per student than regular public schools.

Union leaders say their teachers could get even better outcomes than Bridge if they were given that extra money and smaller classes.

If you had the right conditions and a better salary, a lot of the problem would be solved?

MARY MULBAH, Teachers Union: Yes.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: And when you argued this, what were you told?

MARY MULBAH: The ministry, they’re not even listening to the teachers.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Mary Mulbah blames corruption at the ministry for hiring the ghost teachers and alleges the ministry is using its purges to target union activists.

Immanuel Morris, who was in a government program to train and hire new teachers, says his name was deleted.

Are you a ghost?

IMMANUEL MORRIS, Union Activist: I’m not a ghost, and I can prove that.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: They’re calling you a ghost.

IMMANUEL MORRIS: That is what I’m saying.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: And you’re not a ghost?

IMMANUEL MORRIS: I’m not a ghost.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Union leaders also question whether such programs could be scaled up to serve the 2,750 elementary schools across the country. Minister Werner knows there are risks, but says the government has a moral obligation to take drastic measures.

GEORGE WERNER: It’s not a panacea. And it may just not work. But we should not just fold our arms and do nothing.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Sixty-one-year-old Marie Jaynes couldn’t agree more. She herself had to drop out of school in fourth grade. She now sells water at the side of the road to support her three grandchildren, their parents killed in the civil war.

Jaynes says the new school will give her grandchildren a better life than she has had.

MARIE JAYNES, Grandparent: What hope for them is to go far in school, for them to know the importance of school.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: They are the first of three generations in her family that might enjoy the privileges of at least a primary school education.

For the “PBS NewsHour,” this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Kendaja, Liberia.

JUDY WOODRUFF: A version of this story aired on the PBS program “Religion & Ethics Newsweekly.”

Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

School in a Box

Founded by freed American slaves, Liberia has a past marred in recent years by civil war and Ebola. The country’s public education system is ineffective, and in an effort to rebuild it, the government has reached across the Atlantic for assistance — hiring a U.S.-based for-profit company whose model is “school in a box.” Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports on the controversial plan.

Marked by Suffering

Founded in 1822 by freed American slaves, Liberia is a torn country most recently afflicted with two civil wars and the Ebola epidemic.

GEORGE WERNER

“If we stayed the course, followed the traditional ways of doing things, we wouldn’t catch up with our neighboring counterparts. … What if we had a hybrid for public and private? There are certain things that the private sector does better than the public sector. Government can come up with the policies, but management systems and service delivery, often, the private sector does better than the government.”

Bridge Academy

Bridge provides school with uniforms, textbooks and every teacher is given a computer tablet and is required to stick to pre-loaded lesson plans. There are also new rules, such as no more corporal punishment.

What The Critics Say

Critics of this so-called school-in-a-box approach say it encourages robotic teaching and has allowed Bridge in other countries to hire cheaper, less qualified instructors. Union leaders also question whether such programs could be scaled up to serve the 2,750 elementary schools across the country.