JUDY WOODRUFF: But first: an unlikely innovation from an unusual innovator.

Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro has the story of one man who has made it his mission to bring affordable hygiene products to women in India.

Its part of our series Agents for Change.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Arunachalam Muruganantham says he was a born tinkerer, obsessed with figuring out how things worked, from toys to bicycles. He grew up in poverty after his father died young, dropped out of school and became a welder, a lower-middle-class occupation in India.

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM, Inventor: To support my mother, I stop my schooling.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: But his natural curiosity apparently knew no bounds. Years later, it took him into a strictly taboo area in India’s tradition-bound society: menstrual hygiene.

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: We are able to break the taboo, and using it.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: He’s become known as India’s pad man.

Your goal is to have every woman in this country use sanitary pads, if they need it?

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: Yes, it’s a movement.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: A movement begun by a man who knew almost nothing about the female body until after he was married.

You didn’t even know what menstruation at all. You had no idea what it was. Is that correct?

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: Yes, I don’t know when it is happening, how it is happening, even why it is happening. I don’t know.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: And, he says, his wife, Shanthi, wasn’t particularly interested in discussing it.

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: It’s the biggest taboo. Wife never talks to husband. Daughter never talks to mother.

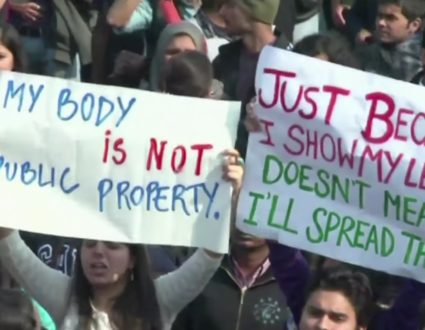

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: That comes at a high cost in public health. Some experts say millions of girls across the developing world miss school during their periods and remain susceptible to infection throughout adulthood.

Sanitary pads are widely advertised in India, but surveys suggest only about one in 10 women actually uses them. At first, Muruganantham suggested them to his wife.

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: I asked simply, there is some products in the market. Why you’re not using that? She instantly told, I also know about that, but we have to cut our family milk budget.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Milk budget?

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: Yes. Then I find it’s a matter of affordability.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: He could afford one package of sanitary pads and gave it to Shanthi as a gift, partly to find out how they were made and why they had to be so expensive.

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: The white substance inside is a cotton. The raw material cost of the cotton is a few pennies. But I bought the product for dollars. Then, even being illiterate, I thought, why not try to make an affordable pad for my wife?

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Over the next few years, he tried, using local cotton, to replicate the commercial pads. His wife suffered through early prototypes that didn’t work and went back to using a rag.

Muruganantham then coaxed some female medical students to try his subsequent models, figuring the future doctors would be less shy. And he even began wearing a pad himself, creating an artificial uterus and rubber bladder, coaxing a local butcher to provide the raw material, and testing it out while he rode a bicycle.

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: I filled goat blood, animal blood in it. I tied on my hip. There is a tube connection to the napkin and the bladder.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Shanthi had had enough.

SHANTHI MURUGANANTHAM, Wife of Arunachalam Muruganantham (through interpreter): Everyone in the village was saying he’d gone off his head. I was truly afraid. People said he had become like a vampire, that he was doing crazy things.

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: She asked me to, “I want to go my parents’ home for a few days.” She never came back. And third month, I got a divorce notice from my wife.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: She filed for divorce?

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: Yes. I got a divorce notice.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: His mother, who lived in the home, also left him. But his curiosity didn’t leave him.

He called an American supplier posing as an industrialist in his hometown of Coimbatore looking to branch out into feminine hygiene products.

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: Then I claim myself, I’m a mill owner in Coimbatore. Please send some samples.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The samples arrived and, one day, when he wasn’t home, his dog tore into them.

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: She took the courier cover. She scratches it. Oh, my God, I saw the secret: the fiber. You can see the fiber.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: So, the dog opened this for you?

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: Opened it. She scratches it with the anger.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: It was cellulose, he discovered, that, when scratched vigorously, becomes sponge-like and highly absorbent.

It took two years to perfect a machine to fluff up the cellulose, he said, a modified food blender in which the blades have to be angled just so.

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: It got a prestigious award from Indian Institute of Technology as the best innovation.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: It’s simple, easily replicated, and can be modified to work without electricity, he says. The pads can be made and sold for a fraction of the commercial varieties.

This is the model for how Muruganantham would like to see his product distributed, thousands of small factories run by groups of women producing these sanitary pads at very low cost and selling them directly to women.

Women are far more comfortable buying the pads from women directly, rather than from a store, Muruganantham says. Feminine hygiene is not discussed in open company. Our own questions elicited nervous laughter from the very women making them, even as they praised their product.

SHANTI UDAYKUMAR, Factory Worker (through interpreter): There’s definitely benefit. Before, we were using only cloth, and it was very difficult. Now girls don’t have that difficulty. It was much easier for them than it was for us.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Muruganantham is determined to change this.

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: I want to make this as a low-cost sanitary pad movement across the globe.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Helped by awards and his own advocacy, more than 4,000 small factories have started making his sanitary pads across India, each with its own local branding and language.

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: Malar is meaning of flower.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: He gets no royalties from any of this. His workshop does sell the machines, enough to earn him a modest living. But nothing is patented. He wants others to copy or even improve the machines and methods.

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: The world has a shortage of solution providers. Everybody want to be in the Forbes list.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Everybody want to be in the Forbes list.

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: Forbes list. Nobody want to be a solution provider.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: In the end, Shanthi decided her husband was a solution provider. She returned after a five-year separation, somewhat sheepishly, she admits.

SHANTHI MURUGANANTHAM (through interpreter): They had his interview on TV that he had discovered sanitary napkins. So I called him, and then I came back. He was angry. I told him I didn’t want to get in his way. That’s why I stepped aside. Now we are happy.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Happy for what her husband’s work may mean for young girls like their 8-year-old daughter, Phrithisri.

ARUNACHALAM MURUGANANTHAM: The strongest creature created by God in this world, not the tiger, not the elephant, not the lion — the women.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: If any man doubts this, he says, see how long you can endure a sanitary pad in your daily routine.

For the PBS NewsHour, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Coimbatore, India.

JUDY WOODRUFF: Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

India’s Pad Man

Breaking a strict taboo in India’s tradition-bound society, Murugananthan worked to perfect an affordable sanitary pad in hope of starting a movement to help women in the developing world. Special correspondent Sam de Fred Lazaro reports.

Classroom resources

A Costly Taboo

The cultural taboo against discussing menstruation comes at a high cost in public health. Some experts say millions of girls across the developing world miss school during their periods and remain susceptible to infection throughout adulthood.

use sanitary pads according to surveys

Why not more?

Apart from the cultural taboo, many women in India cannot afford the luxury of sanitary pads. The matter of affordability is what inspired Arunachalam Muruganantham to find an alternative.

Arunachalam Muruganantham

“The world has a shortage of solution providers. Everybody want to be in the Forbes list. … I want to make this as a low-cost sanitary pad movement across the globe.”

Woman to Woman

The model is simple, easily replicated, and can be made and sold for a fraction of the commercial varieties. Muruganantham would like to see his product distributed by thousands of small factories run by groups of women producing these sanitary pads at very low cost and selling them directly to women.