JUDY WOODRUFF: But first: More than three million migrant workers every year, most of them women, leave their countries to work as domestic laborers, often in conditions some say border on slavery.

Human trafficking is especially grave in the Persian Gulf and the Middle East.

Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro begins his report from the West African nation of Cameroon. It’s part of his series Agents for Change.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: They’re able to laugh at it now in a workshop setting, but the skit these women are watching depicts experiences that are all too real.

These women are all survivors from time spent in Persian Gulf and Middle East countries where they were domestic workers, victims of an industry the U.N. and rights groups say is rife with human trafficking and abuse.

Three years ago, Francisca Awah was working as a secretary in Cameroon and helping her mother sell vegetables. She had a new baby and with her fiance wanted to build a nest egg. So, Awah, who has a college degree, jumped at what she thought was a teaching job offer in Kuwait for 10 times her salary in Cameroon.

She paid the sponsoring agency $500, plus airfare. But almost as soon as she landed in Kuwait, she knew something was wrong, an experience familiar to many in this audience and acted out in the skit.

WOMAN: You no like, you give me $6,000, you go back to your country.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The bait and switch, an agent or trafficker demanding large sums if they weren’t satisfied with their job or pay, in Francisca Awah’s case, not teaching, but cleaning.

FRANCISCA AWAH, Trafficking Survivor: He started telling me, you’re going to work with me as a maid. You will take care of my two children and the house chores.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Awah says she complained and asked for her passport back, so she could return home. Although it’s illegal, workers’ passports are routinely confiscated by employers. The employer’s wife refused, saying she had paid the agency $2,000 for her services.

FRANCISCA AWAH: And the lady was so angry that she pointed at the television and told me that, Francisca, you know something? You are like that television. You are a commodity. I bought you. You need to pay back my money before you leave.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: She had bought you?

FRANCISCA AWAH: Yes.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Then, one day, Awah saw a news report about an organization, Freedom For All, headed by an American woman named Katie Ford.

KATIE FORD, Freedom For All: And she said, please help me. There are many in much worse situations. Please help us all.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Indeed, Awah’s story is far from unique. Each year, more than three million women worldwide are forced into servitude as domestic workers. Ford was shocked when she learned the extent of the problem.

KATIE FORD: Why aren’t we calling this slavery? It’s people being forced to work without pay, without an ability to escape.

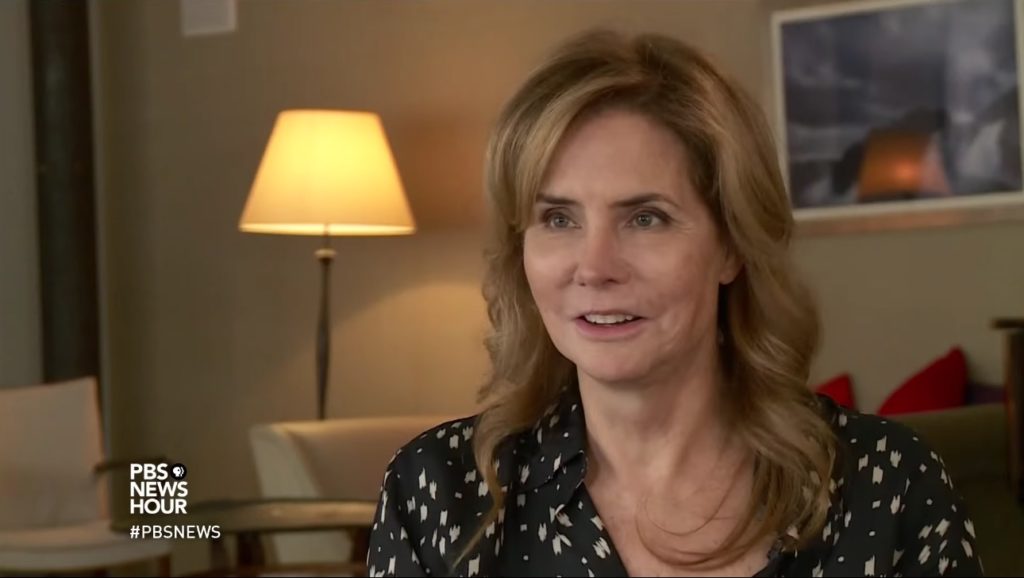

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Katie Ford is the former CEO of the renowned Ford Modeling Agency. Her parents started the business in 1946, and represented such high profile models as Elle Macpherson and Naomi Campbell, bringing standards to an industry notorious for taking advantage of young women.

Ford was the first agency to insist that models be paid a fair wage.

KATIE FORD: They made sure the client paid, and they made sure the models were protected.

This is the first picture of her I saw.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Just as her parents did for their models, Katie Ford says she wanted to advocate for domestic workers. Her goal was to form partnerships with governments, employers and human rights organizations.

One of the first places she started was Kuwait, an oil-rich state of nearly four million people where foreigners outnumber native Kuwaitis by 2-1. It is the only country in the Persian Gulf region to even acknowledge there’s a problem with domestic workers.

Kuwait became the first country in the Gulf region to pass a law that attempts to protect the rights of domestic workers, requiring at least one day off a week, for example, and setting the maximum number of hours worked per week. It’s not much. That maximum is 72 hours. And the law doesn’t specify that the worker be allowed out of the home on that day off.

And many, in fact, are forced to remain in their employer’s home on their day off. The Kuwait government has established a shelter, with a capacity for 500, where foreign domestic workers can escape abusive employers.

We were given a rare tour of the facility by its director, Falah al Mutairi.

FALAH AL MUTAIRI, Director of Labor Housing, Kuwait (through interpreter): The services that are provided include legal services, social, cultural and emotional help if needed. When it comes to deciding what the next step is, it’s up to the individual herself. Does she want to stay in the country? That’s when we discuss options. Ninety percent of the women want to go back to their home countries.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Since the shelter opened two-and-a-half years ago, nearly 8,000 women have passed through, waiting for passports to be returned, trying to find the means to buy return tickets, sorting out various legal problems.

We spoke with five women from countries as diverse as Madagascar, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, Nepal and the Philippines. All said they were either unpaid or severely underpaid. Many were lured here under false pretenses.

Nineteen-year-old Hassanatu Bangura says her parents thought they were sending her to college.

HASSANATU BANGURA, Trafficking Survivor: I think I’m going to start school. So we go to the office, and she said that I’m going to work.

BIBI NASSER AL SABAH, Social Work Society of Kuwait: We have a domestic labor law, but we don’t have clear punishments or punishments that are enough to make an employer stop.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Bibi Al Sabah is a member of Kuwait’s ruling family. Twelve years ago, she founded an organization designed to get workers legal help, also, she says, to change the culture, and attitudes toward domestic workers.

BIBI NASSER AL SABAH: We’re rich people, and we can afford to have people working for us. And so, with this idea, a lot of people eventually just lost track of how humans should behave. It became part of the culture now to have workers everywhere. And so people forget that they’re humans and forget that these people are — have lives and have children and have their dignity.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Falah Al Mutairi acknowledges that more reforms need to happen, but he’s convinced that Kuwait has turned a corner. And he says that, to truly eradicate the problem, traffickers must be held accountable in the workers’ countries.

FALAH AL MUTAIRI (through interpreter): Because of sovereignty issues, Kuwait cannot track down criminals in other countries. It can’t do anything about people outside its jurisdiction.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Francisca Awah isn’t sure she can stop the traffickers either, but she is trying to help the desperate economic plight of women in low-income countries like Cameroon. After being rescued by Katie Ford 18 months ago, the two women have teamed up to form a career training program for women in this West African country

FRANCISCA AWAH: I wish that the girls should be like empowered personally. They should learn to do something within their country.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Last fall, Awah led a workshop with 34 young women who fled abusive work situations in the Middle East. They were learning how to finance and start their own businesses.

It included field trips to restaurants and markets to learn from other entrepreneurs and team-building exercises.

WOMAN: You wake up. You clean everywhere, OK?

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Gatherings like these have helped women overcome, even laugh at their traumatic experiences, and maybe, they say, spread the word to other would-be trafficking victims.

For the PBS NewsHour, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Kumba, Cameroon.

JUDY WOODRUFF: Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

Modern Slavery

More than three million migrant workers every year, most of them women, leave their countries to work as domestic laborers, often in conditions some say border on slavery.

Human trafficking

Human Trafficking is a $150 billion industry, the third largest criminal activity in the world after drug related crimes and counterfeiting. Much of the market for labor trafficking comes from the Persian Gulf and the Middle East.

The Promise of Employment

Francisca Awah was working as a secretary in Cameroon and helping her mother sell vegetables. She had a new baby and with her fiance wanted to build a nest egg. So, Awah, who has a college degree, jumped at what she thought was a teaching job offer in Kuwait for 10 times her salary in Cameroon. Almost as soon as she landed in Kuwait her passport was confiscated and she was forced into cleaning as a maid. Then she saw an ad for Freedom for All.

Katie Ford