HARI SREENIVASAN: But first: trying to meet the education needs of refugee children in a resource-poor country overwhelmed by new arrivals.

Just yesterday, the United Nations announced one million South Sudanese refugees had arrived in Uganda over the past year. Many have ended up here at the Bidi Bidi camp, the largest in the world.

Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports, part of his series Agents for Change.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: It’s not often you will find a school in Africa that provides meals to its students.

JOSEPH MUNYAMBANZA, Educational Entrepreneur: We give them breakfast and lunch.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: You didn’t get this when you went to school?

JOSEPH MUNYAMBANZA: No.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: It not only helps students focus on learning, but this simple plate of corn, or maize, and beans may also be the reason many show up at all.

The school’s 30-year-old founder remembers packed classrooms when he started primary school, but they didn’t stay that way for long.

JOSEPH MUNYAMBANZA: Over 150 children, but I remember, by the time I was in primary seven, we had about 15 children left.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Lots of children drop out?

JOSEPH MUNYAMBANZA: They drop out, and the problem is connected to food.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Joseph Munyambanza was born in the Democratic Republic of Congo, but his parents, like tens of thousands of others, fled to Uganda when he was 6.

For decades, Uganda has welcomed refugees from its war-torn neighbors, but even with United Nations’ help, its resources are very limited.

Rwanda? Congo?

Last year, I visited a school in Nakivale, a refugee settlement in southern Uganda. No lunch here, and not much learning, in classrooms crammed on average with 120 children. Few of the hundreds of thousands of refugee children in Uganda make it into high school, for which they must pass a national entrance test.

Joseph Munyambanza was one of those few. He completed high school, and received a scholarship to the prestigious African Leadership Academy in South Africa founded by a group of Stanford alumni. Another scholarship from the MasterCard Foundation got him to Westminster College in Missouri, where he got a degree in biochemistry.

It was a heady journey, far from his humble beginnings, but he says, he never forgot them.

JOSEPH MUNYAMBANZA: When I finished my degree, I already had my ticket to come back, and most kids say, you’re crazy. You’re not serious, because that standard is, you go there, you finish your degree, and you get a job and start getting money.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: One big reason he returned was an organization he’d founded while still in high school with a few friends. They volunteered to mentor and tutor younger refugee school children.

And as Munyambanza traveled in the West, he was able to network with donors, raising funds for their group, called Coburwas, and for a primary school it runs in the refugee settlement of Kyangwali.

The 433 students are urged to think critically, in a country where rote learning is the norm. And they’re taught farming on land adjacent to the school. In Uganda, refugees are provided small plots of land and school parents also contribute produce.

JOSEPH MUNYAMBANZA: We raise around five tons of maize, and part of it has to be eaten, but a bit part of it has to be sold to bring money to support the projects.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: So far, Coburwas has helped some 1,600 students pass the high school entrance exam, and placed many of them in better-resourced high schools, away from their refugee settlements, where they now attend alongside Ugandan children.

Coburwas pays their tuition room and board. We visited this school in the town of Hoima, about two hours from the refugee camp, and talked with Coburwas scholars about their goals.

STUDENT: I would like to be a genetic engineer.

STUDENT: A civil engineer.

STUDENT: I would like to become a doctor, because I have seen people suffering a lot.

STUDENT: I would like to be a lawyer.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: A lawyer?

One of their biggest problems, they said, is the stigma of being refugees, often taunted that they are freeloaders.

STUDENT: Some of them also don’t feel well when they see us studying, yet we are not Ugandans.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: So they feel somewhat resentful that you are being paid for, supported, and Ugandans are not?

STUDENT: Yes.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Joseph Munyambanza says he faced the same problem when he went to school. That’s why a Coburwas counselor is always on hand.

WOMAN: We have a big vision for you. We do this because we believe you are the leaders of Africa tomorrow.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Several alums have been launched toward leadership roles, attending universities across Uganda and as far away as Arizona State and Munyambanza’s alma mater in Missouri.

Twenty-three-year-old Favourite Regina just received her degree in development studies from the United States International University in Nairobi, Kenya, a stint that took her to France and could have landed a well-paid job in a lot of places. But she returned home to teach at the Coburwas primary school.

FAVOURITE REGINA, Primary School Teacher: We feel like coming back to our communities and helping the other people grow, it’s very important, so that we come together as a collective community.

JOSEPH MUNYAMBANZA: Those who are given, those who are trusted, much more is expected from them.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: He says improving the education system is the first step in rebuilding communities defined and created by war, to open the eyes of children who have known little more than life in a refugee settlement.

For the PBS NewsHour, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro, in Kyangwali, Uganda.

HARI SREENIVASAN: Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

Refugee to Educator

Many ended up at the Bidi Bidi camp, the largest in the world. Joseph Munyambanza is a refugee who returned after studying in the U.S. to try to meet the education needs of refugee children in this resource-poor country overwhelmed by new arrivals.

It starts with lunch

It’s not often you’ll find a school in Africa that also supplies lunch. It not only helps students focus on learning, but this simple plate of corn, or maize, and beans may also be the reason many show up at all.

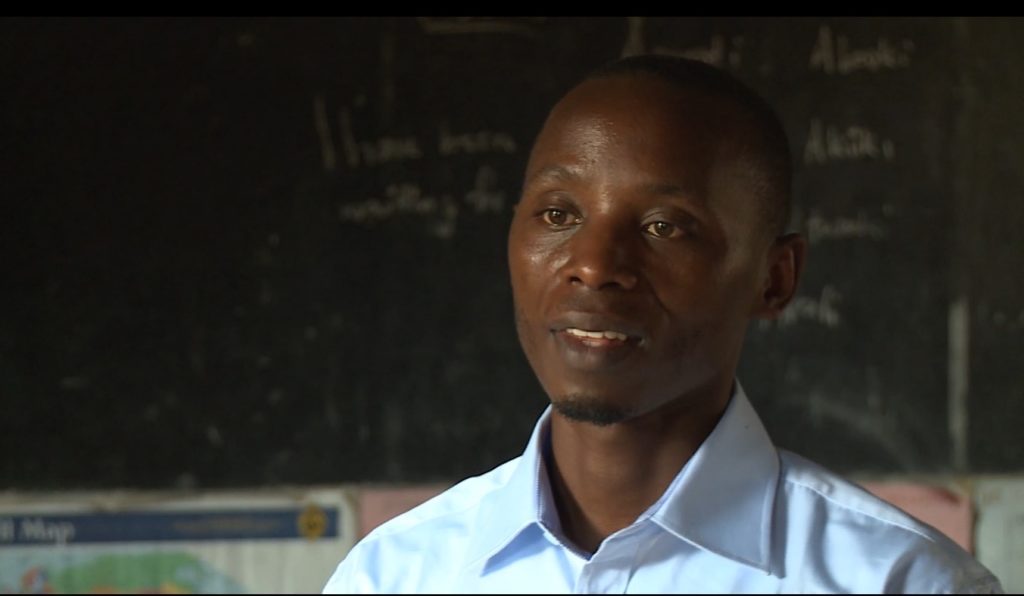

Joseph Munyambanza

Joseph Munyambanza was born in the Democratic Republic of Congo, but his parents, like tens of thousands of others, fled to Uganda when he was 6.

He was lucky enough to complete high school, and received a scholarship to the prestigious African Leadership Academy in South Africa founded by a group of Stanford alumni. Another scholarship from the MasterCard Foundation got him to Westminster College in Missouri, where he got a degree in biochemistry. It was a heady journey, far from his humble beginnings, but he says, he never forgot them.

Critical Thinking and Farming

The 433 students are urged to think critically, in a country where rote learning is the norm, and they’re taught farming on land adjacent to the school. In Uganda, refugees are provided small plots of land and school parents also contribute produce.