Judy Woodruff: But first, when it comes to providing innovative health care, Pakistan is not a country that usually comes to mind. But in Karachi, one public-private partnership is trying to address some of Pakistanis’ most pressing medical needs. In cooperation with the “Associated Press,” special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro has the latest in our series, “Agents for Change”.

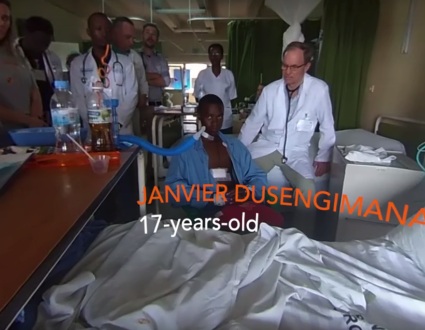

Fred De Sam Lazaro: On any given day at Karachi’s Jinnah Hospital, some 5,000 patients arrive, many wheeled in on rusty, bare metal gurneys by family members who wait sometimes for days in the outer corridors. Inside are long lines-for X-ray scans or appointments with overwhelmed staffers. There are lots of exhausted children. Jinnah is one of the oldest, biggest public health care facilities in Pakistan’s commercial capital, a city of 15 million and the hospital hasn’t been immune to the violence and terrorism that has gripped this country, including this bomb blast in 2010 in its own emergency department.

Dr. Seemin Jamali: We nearly missed to die. I was standing right at the gate and very, very injured. About 18 people lost their lives at that point.

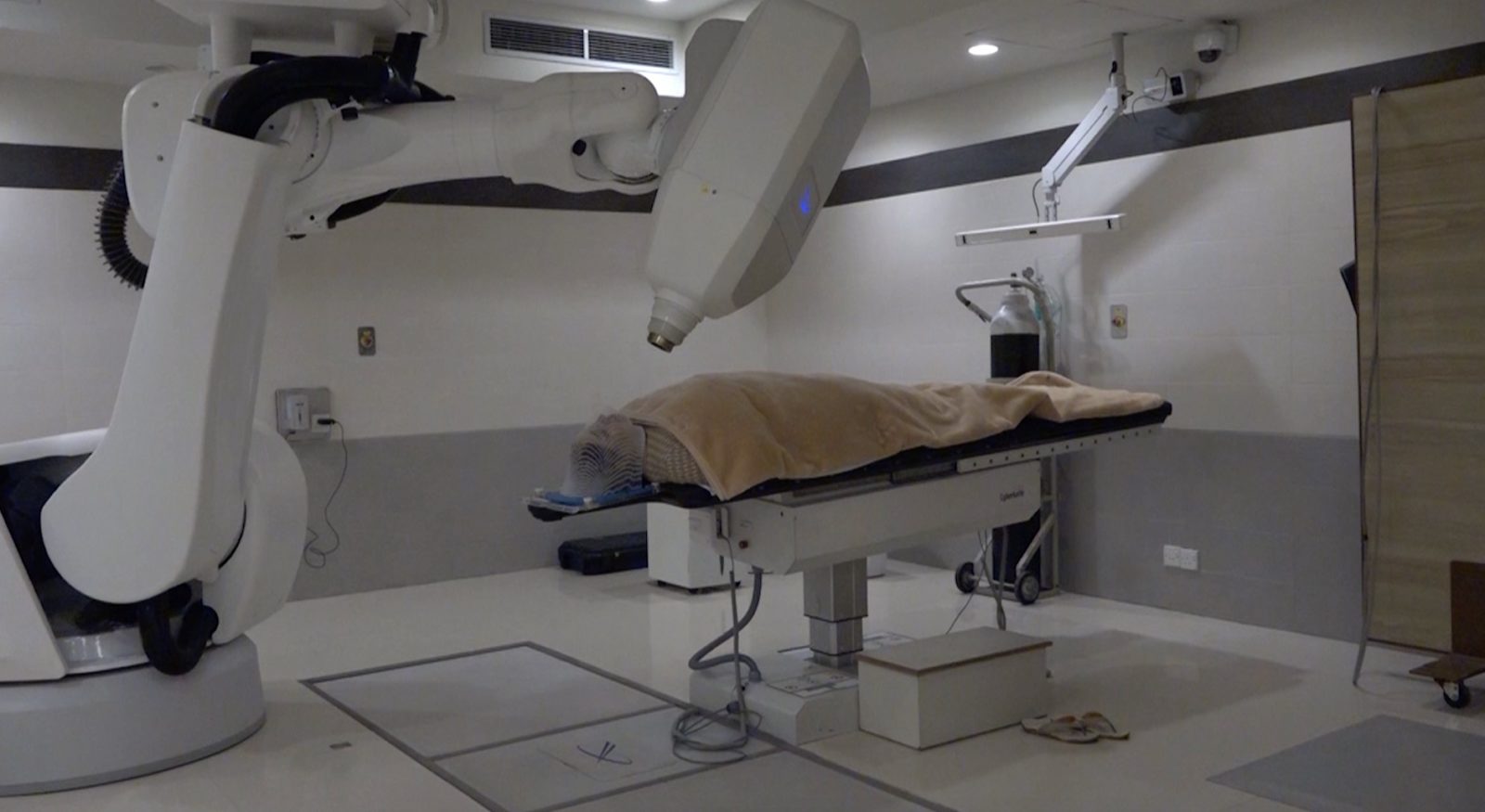

Fred De Sam Lazaro: Yet hospital CEO Seemin Jamali notes that just 30 seconds after the blast, staff are back on their feet, tending to the injured. She says it’s a metaphor for a hospital that is transforming itself amid all the chaos, replacing its decrepit old buildings and bringing some of medicine’s most modern equipment and care to Pakistan’s poorest patients who may never otherwise have access. Six-year-old Noman Azim was brought in after losing his sight when a growing brain tumor began to affect his optic nerve.

Sheena Azim: (Through interpreter) He was scared of everything. He lost his eyesight for two months. He was completely blind. Thank God my son has a new life. He goes to school, he studies, he plays outside.

Dr. Tariq Mahmood: This is pre-treatment images. And this is post-treatment images. Look at this, that whiteness has almost completely gone.

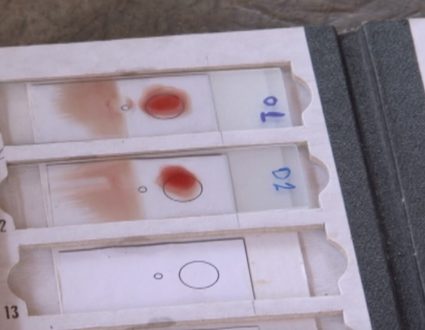

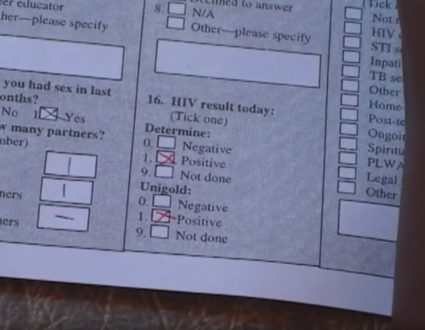

Fred De Sam Lazaro: Radiology chief Dr. Tariq Mahmood (ph) says Noman was treated with some of the most sophisticated technology anywhere. He was restored to sight with a $4 million robot like device called a cyberknife. In the U.S., the price tag for such treatment ranges between $50,000 and $90,000. Here it is free, true of all services in government hospitals. Patients can chip in after their care but it’s voluntary. On average, these donations defray about eight percent of the hospital’s costs. All this equipment was donated to the hospital by a non-profit group called the Patient’s Aid Foundation, private citizens who’ve provided guidance and much of the funding for the hospital’s facelift.

Dr. Tariq Mahmood: From 1984 to 1994, we were doing 200 scans in a year. Today, we are doing 300 scans, CT scans in a day.

Fred De Sam Lazaro: This public private partnership began in 1992, when a group of business leaders were moved by the desperate conditions at the hospital. Businessman Mushtaq Chhapra says it began with pleas from the hospital to replace broken refrigerators in the blood bank and parts for medical equipment.

Mushtaq Chhapra: The government didn’t have the budget to do these repairs or renovation. And this is where my organization stepped in and virtually, these were small things which were remedied within hours.

Fred De Sam Lazaro: Those small things have added up quickly; $35 million so far, in donations from prominent business families in Karachi, for buildings, equipment and some staff at the hospital. Chhapra says at first they were skeptical about partnering with a public sector notorious for inefficiency and corruption. He says they forged a clear understanding of key roles each side would play.

Mushtaq Chhapra: We have not let the government abdicate their responsibility. The government has 3,000 people working in this hospital, the government is paying salaries for those people, the government provides the utilities, the medications. What we do is we bring the ideas, we bring the systems and we bring the much-needed equipment.

Dr. Tasneem Butt: Doctors, obviously everybody wants to work in a neat and clean environment.

Fred De Sam Lazaro: Retired radiologist Tasneem Butt volunteers as a patient advocate at the Jinnah Hospital. She says the upgrades have not only improved patient care but also morale among providers.

Dr. Tasneem Butt: We did not have any mammography machine. It took like 20 years for us and now as I speak of, we have the latest technology of mammography machines. And this is probably the largest radiology center in Asia.

Fred De Sam Lazaro: It is large and state of the art but ironically, it is perhaps the least busy section of a very busy hospital, even though the incidence of cancer is growing in Pakistan, including the highest rate of breast cancer in Asia. A lot of the cancer that occurs in Pakistan goes untreated. Patients in many cases can’t afford therapy, if it’s available. And even in places where it is available, doctors say the vast majority of patients come in in advanced stages, when it’s too late for any effective treatment. That was the case with this seven-year-old boy, brought here by his father from Peshawar, a city some 850 miles away near the Afghan border. His brain tumor had progressed too far to benefit from radiotherapy. Dr. Tariq Mahmood says only five percent of the cancers seen here are in the early treatable phases.

Dr. Tariq Mahmood: There is lack of the availability of the proper equipment for the early diagnosis. And at the same time, there is lack of education.

Fred De Sam Lazaro: Public education is a big challenge, but Dr. Mahmood says the Jinnah Hospital offers a model for delivering high quality care to the poor. A public private partnership is inherently fragile amid Pakistan’s volatile politics but the foundation’s Chhapra says he’s not deterred.

Mushtaq Chhapra: We are pumping in millions and millions of dollars into a hospital which is owned by the government. Tomorrow, they may turn around and say enough is enough. Get out. We as a group have decided, come what may, we are here to stay.

Fred De Sam Lazaro: And despite the challenges, the foundation has ambitious plans to expand. A state of the art, $25 million outpatient department is slated to open early in 2018. For the PBS NewsHour, I’m Fred De Sam Lazaro in Karachi, Pakistan.

Judy Woodruff: Fred’s reporting is part of the Under-Told Stories Project at University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

Jinnah Hospital

Jinnah Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan, has long served the poorest patients despite, desperate conditions, overwhelming demand, and even falling victim to terrorism. A public-private partnership has helped the government hospital make modern updates to its equipment and care. In cooperation with the Associated Press, special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports.

The Patient’s Aid Foundation

All this equipment was donated to the hospital by a non-profit group called the Patient’s Aid Foundation.

Mushtaq Chhapra