Judy Woodruff:

Now, a glimpse into the vast, global, and criminal business of fake pharmaceutical drugs.

Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports on how some medical providers in Kenya are trying to ensure that patients receive genuine prescription drugs. It’s part of his series, Agents for Change.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:

Catherine Karimi has been a nurse for 30 years. But for the last nine, she’s also been a businesswoman. She owns a franchise in Nairobi of a CFW Clinics, owned by a U.S.-based group called the Health Store Foundation.

So your business is very good? Very busy then?

Catherine Karimi:

Yes, I can’t complain.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:

Much like a fast- food chain, health store supplies Karimi and all franchisees with lab equipment, training, marketing and standardized procedures. Perhaps most importantly, it also supplies clinics with genuine drugs, containing what’s on the original label.

Catherine Karimi:

They feel that our drugs are original. That’s why they come here.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:

Twenty-three-year-old Edah Mokua came here after the drugs she bought at a nearby pharmacy failed to cure a urinary tract infection.

Female:

They did not work at all.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:

So-called fake pharmaceuticals are a multi- billion dollar problem around the world. They are made and packaged to look like real drugs, but contain a fraction of the active ingredients need to be effective, sometimes containing nothing but chalk.

Thomas Woods, a consultant to the World Bank, worked on this issue while serving in the George W. Bush administration.

Thomas Woods:

These are major global, international crime syndicates with far reach. These guys are killers. They’re murdering people and they’re taking something that we all rely on and they’re callously and cynically putting out fake medicines.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:

A newly-released report by the World Health Organization found that one in ten medical products in developing countries is substandard or falsified. A Lancet Medical Journal study found that 20 percent of malaria drugs were fake.

James Owour is with Kenya’s pharmacy and poisons board which regulates drugs. He complains his agency is hampered by too few inspectors, only 16 for the entire country, and no legal muscle.

There’s no law against a pill made out of chalk?

James Owour:

Not in our acts.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:

It must be a real frustration?

James Owour:

Sure it is. The other challenge is porous borders. People smuggle things including medicine through places that are not manned by inspectors and such.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:

In response, many providers have developed their own methods to ensure quality, inspections are regularly conducted at CFW Clinics, for example.

Abraham Orare explained what he looks for.

Abraham Orare:

When we’re looking at the source, we’re looking at the stock card and also cross-checking the delivery sheets to make sure this is exactly what is being supplied.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:

Their supplier is a not-for-profit group called MEDS, Mission for Essential Drugs and Supplies. It was founded 30 years ago by faith-based groups, which are major health care providers in Kenya. MEDS now distributes 40 percent of all drugs in Kenya from its giant warehouse on the edge of Nairobi.

Jane Masiga:

We have more than 1,300 items which pass through us.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:

Some of the most commonly prescribed are also most commonly counterfeited, says MEDS director Jane Masiga.

Jane Masiga:

Antibiotics, painkillers and medicines for chronic diseases. Because they know that’s a regular supply, patients will continue taking those medicines.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:

Before they reach its Nairobi labs, MEDS begins its process by inspecting the factories where the drugs are made, in Kenya and also in India and China — two of the biggest sources of pharmaceuticals, both legitimate and counterfeit.

Stephen Kigera is in charge of quality assurance for MEDS.

Stephen Kigera:

So, we’re able to actually pick out some of the non-conformities that are found in some of these factories.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:

MEDS randomly tests the drugs that it buys. Those that fail are destroyed to insure that only genuine products leave this warehouse for clients’ shelves. But Kigera says there are other complications. Many small, storefront pharmacies buy from unauthorized distributors, and are staffed by unqualified people dispensing drugs without any pharmacy training or a prescription.

Stephen Kigera:

Those pharmacies and chemists which are run by quacks or non- professionals, those are the chemists where there is a high likelihood that fake medicines will actually be sold.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:

Does the average patient have any awareness that this is a problem?

Stephen Kigera:

Chances are no, because, assuming I’m from a poor neighborhood, if I see somebody standing behind the counter and wearing a white lab coat, I assume the person is a professional.

Dr. Mercy Maina:

Pop open a capsule.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:

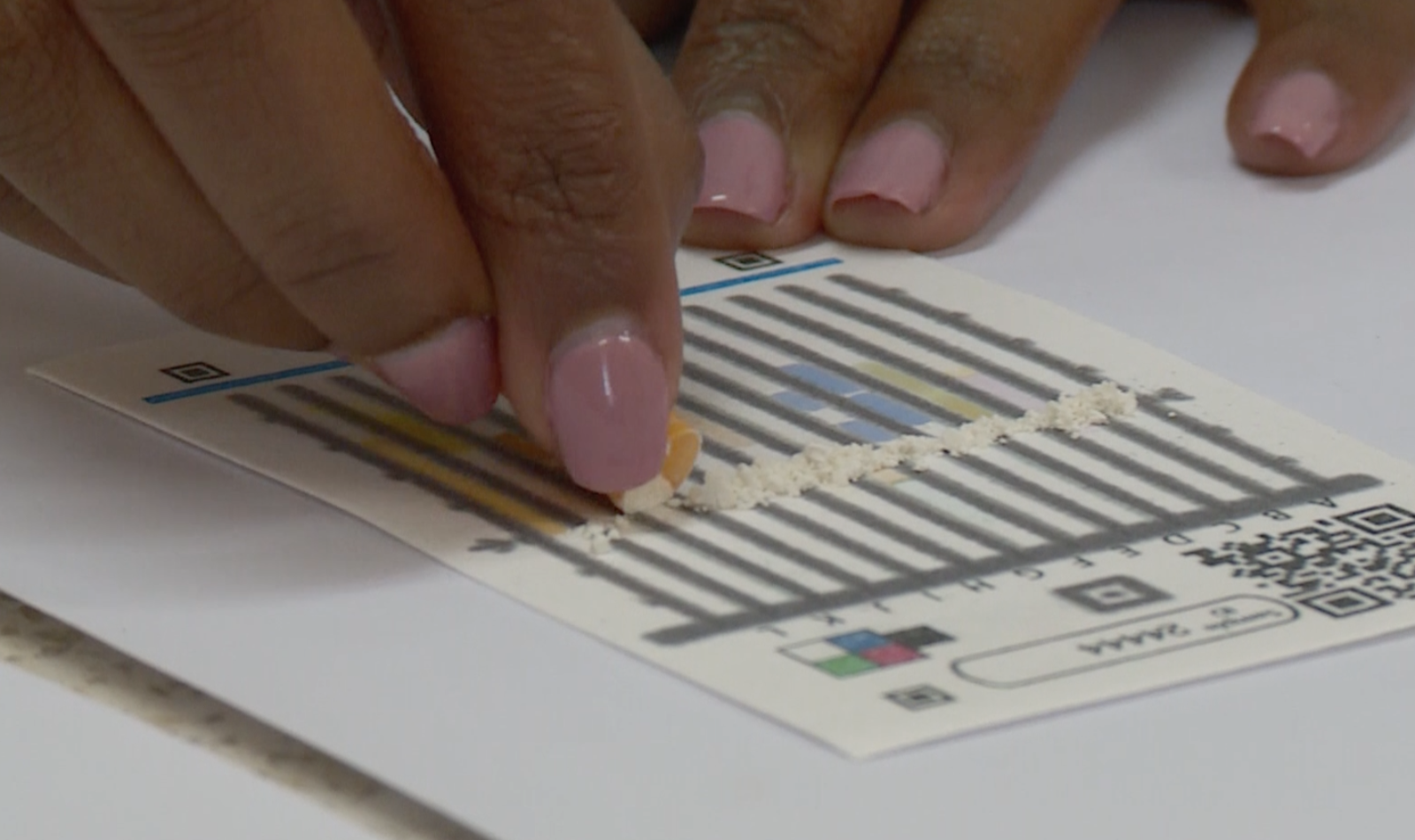

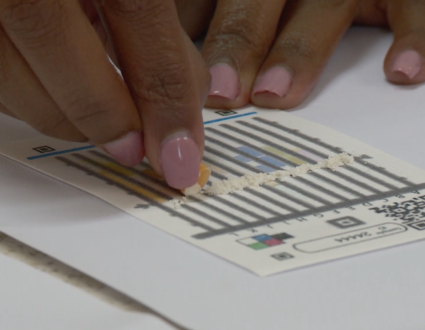

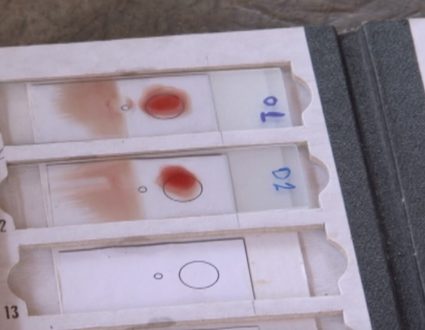

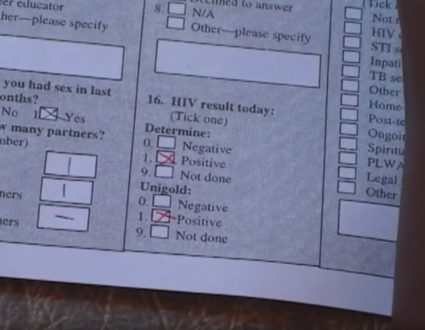

Technology may provide some answers — everything from bar coding to chemical markers to weed out fakes. Here at the Moi hospital in Eldoret, a team from Purdue and Notre Dame Universities is in the early testing phase of a chemically coated paper strip. It’s cheap, just 50 cents a card, and easy to use by a clinic for instance to test its drugs supply. Spread it on the card strip, dip in water and check for color changes.

Dr. Mercy Maina:

If there are any differences between the image and the control image, then you can say it’s suspicious.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:

Suspicious means it doesn’t contain the active ingredient or has only a tiny fraction of it, as often happens, says Dr. Mercy Maina.

Dr. Mercy Maina:

Counterfeiters are smart. They know you’re going to run a qualitative test to just test the presence of the active pharmaceutical ingredient. They will make sure that some of it is available for it to pass the test, right, to just be able to get away with it.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:

The new test should be able to detect products with those smaller doses of active ingredient, which she says are a giant threat to public health, especially with antibiotics which the bacteria learn to resist.

Dr. Mercy Maina:

You’re increasing superbugs. So we will run out of antibiotics because you’re being always exposed to lower quantity of medication than you should. That has consequences.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:

Thomas Woods agrees.

Thomas Woods:

I think it’s a system failure if we are not able to equip partners in places like Africa with some of the same tools that we use to protect ourselves- technology, field-based technology, stronger laboratories, rapid authentication devices, things that our Food and Drug Administration has at its disposal. Let’s put them in the hands of African regulators so that we can save African lives.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:

Part of his job at the World Bank is to convince rich countries to step up such efforts. It’s not just African lives at stake, he says, but the safety of the global supply of pharmaceutical drugs.

For the PBS NewsHour, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Eldoret, Kenya.

Judy Woodruff:

Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Undertold Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

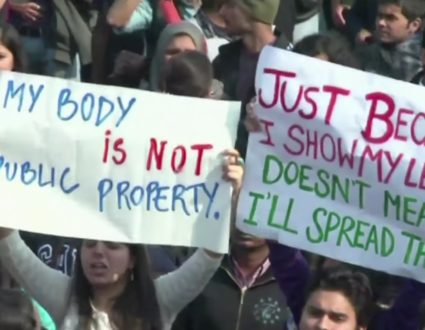

A Global Health Threat

Fake pharmaceuticals are a multi-billion dollar problem around the world. Made and packaged to look like the real deal, these phonies may contain a fraction of the active ingredients or none at all. These fake drugs can have serious consequences in countries with tenuous health care, as well as in the developed world. Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports from Kenya.

Inspection and Detection

To fight the counterfeit drug market, Kenya’s pharmacy and poisons board conducts pharmacy inspections and drug tests but its director says his agency is hampered by too few inspectors, only 16 for the entire country, and no legal muscle.