Hari Sreenivasan:

Next: one effort to address a humiliating medical injury that afflicts perhaps one million women in the developing world who lack access to safe medical facilities.

Fred de Sam Lazaro reports from Kenya. It’s part of his Agents for Change series.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

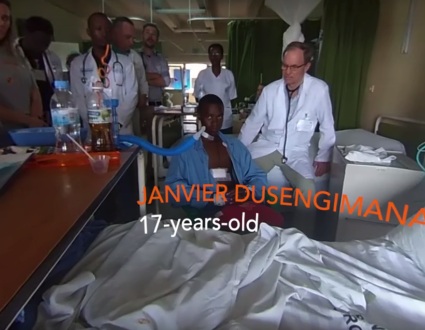

In a new hospital in Eldoret, Kenya, these women are awaiting surgery to fix a condition that’s widely misunderstood and reviled, one that’s made them outcasts, often in their own families.

It’s called obstetric fistula, an injury to the birth canal caused, in most cases, by prolonged labor that leaves a woman incontinent. Perhaps one million women in the developing world suffer from fistulas, a condition virtually wiped out in industrialized nations with better access to prenatal care and medical facilities.

At least once a week, these patients hear a message of hope from a woman who knows all too well their suffering; 41-year-old Sarah Omega was just 19 when she was raped and became pregnant.

Sarah Omega:

I was so scared. I didn’t want to secure an abortion because of my faith, yes, so I kept the pregnancy.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Omega eventually spent 38 hours in a difficult labor, much of it at home. In the process, the baby died, and she suffered a large fistula. For 12 years, Omega says she was subjected to isolation and shame.

Sarah Omega:

I attempted suicide twice. Every night, I would go to bed. I would say, God, please don’t allow me to see tomorrow, because my tomorrow, every day, I would wake up in the morning, see the sun, I would cry because I knew it was another day of pain, of humiliation, of suffering in isolation.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

That anguish landed her in a psychiatric ward, and it was there that a visiting doctor came to her bedside.

Sarah Omega:

He assured me that my problem was going to be fixed. And I remember that day he told me: “I’m seeing a lot of hope in you. I want you to get healed.”

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

That doctor was 49-year-old Hillary Mabeya, a gynecologist and surgeon who has devoted his entire practice to women with fistulas.

This 88-bed hospital was built for his use, as part of a broad campaign by the California-based Fistula Foundation.

Hillary Mabeya:

These are patients who need care, they need support, and they need a lot of counseling. They suffer so much from society because of their condition.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

It’s difficult to pinpoint how many women suffer from fistula in this country, in part because most of them are kept isolated by their communities and even their families.

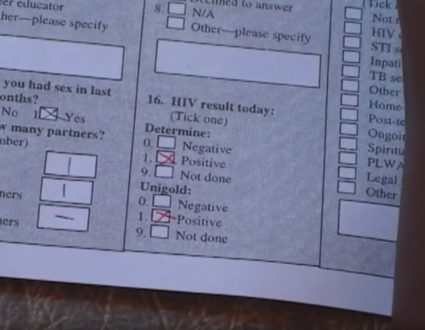

But in recent years, since the campaign began to raise awareness of fistula, awareness that it is treatable, some 7,000 women have emerged from hiding each year seeking surgery.

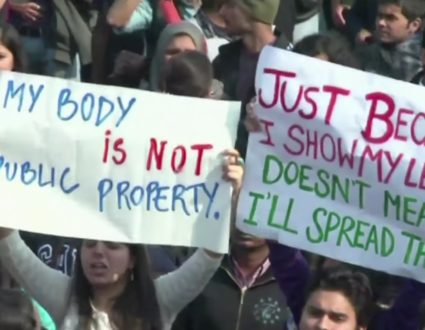

Fistula awareness groups have taken to the streets to educate others about the condition, and where to get help. We watched as these women, many of them survivors themselves, fanned out through the Western city of Mumias, and encouraged women suffering from incontinence issues to get free screening offered by the campaign.

Organizer Habiba Mohamed said people still have many misconceptions about fistula.

Habiba Mohamed:

Maybe she has been bewitched. Maybe she was promiscuous and had a relationship outside marriage when she was pregnant.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Mohamed’s group, WADADIA, recently arranged the transportation and treatment for 35-year-old Rachel Juma Wasamba, who lives in a remote village in Western Kenya.

Wasamba was lucky. Her husband stayed with her throughout her condition and treatment. Many husbands abandon their wives in such situations.

Amina Mushele says that’s what happened to her.

Amina Mushele:

(Through interpreter) My husband couldn’t take it anymore, so he left me to marry another woman.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

She had surgery one year ago, and now makes and sells goods in the town marketplace, using skills she got from a training program sponsored by WADADIA. The training, ranging from hairstyling, to seamstress work, and computer skills, helps reintegrate women back into their community.

Habiba Mohamed:

The moment someone has been treated, and she has healed, you can be able to see a significant change in her life, and not only in her life, in her family, in her children. So, it has a ripple effect to an entire family and the entire community.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Back in Eldoret, Dr. Mabeya is kept very busy at one of the few places where fistula surgery is performed and offered free of charge.

Working six days a week, he operates on 45 women a month. Since that’s just a fraction of the new cases, he is also training other doctors in the region, and he is working to prevent fistulas in the first place.

Hillary Mabeya:

Fistula is almost 100 percent preventable. In developed countries, it’s not even there.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

He says fistula can be avoided if adequate prenatal and emergency care is made available when complications arise during pregnancy. More than half of all Kenyan women still deliver their babies at home.

For her part, Sarah Omega says her healing became complete when she able to give birth to a health baby daughter, Jade, who recently turned two.

Sarah Omega:

She means just the whole world to me. I remember at some point, I would pray and say, God, if you give me a baby, that baby will erase the pain I have gone through in this life.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

And Omega continues to help other women erase the pain of fistula.

Sarah Omega:

I decided to change the pain I had gone through into something beautiful, something that will help me reach out to other women, something that will allow other women to live a normal life like me.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

She travels frequently to talk about her experiences, but, more regularly, her advocacy happens at the bedside of women at the new fistula hospital.

For the PBS NewsHour, I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro in Eldoret, Kenya.

Hari Sreenivasan:

Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

Suffering in Silence

Roughly one million women in the developing world suffer from obstetric fistula, an injury that results from inadequate medical care and causes incontinence. But beyond the physical effects, the condition can subject them to shame and isolation from their families. Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports from Kenya on efforts to offer treatment and reintegrate women back into communities.

Spreading the Word

It’s difficult to pinpoint how many women suffer from fistula in this country, in part because most of them are kept isolated by their communities and even their families, so a campaign of survivors is reaching out to women individually and in public to fight the taboo.

Sarah Omega