William Brangham:

But first- combining school and work to build a brighter future for employees and their communities.

In his final report from El Salvador, Fred de Sam Lazaro visits a garment factory that hires workers who are normally left out of society, including ex-gang members.

It’s part of Fred’s series Agents for Change.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Fifty thousand T-shirts and sweatshirts buzz through the sewing machines in this factory every week, bearing the seals and mascots of some 1,600 U.S. universities, Princeton, Michigan, Kenyon College, each one, it seems, a reminder to general manager Rodrigo Bolanos of what El Salvador desperately needs.

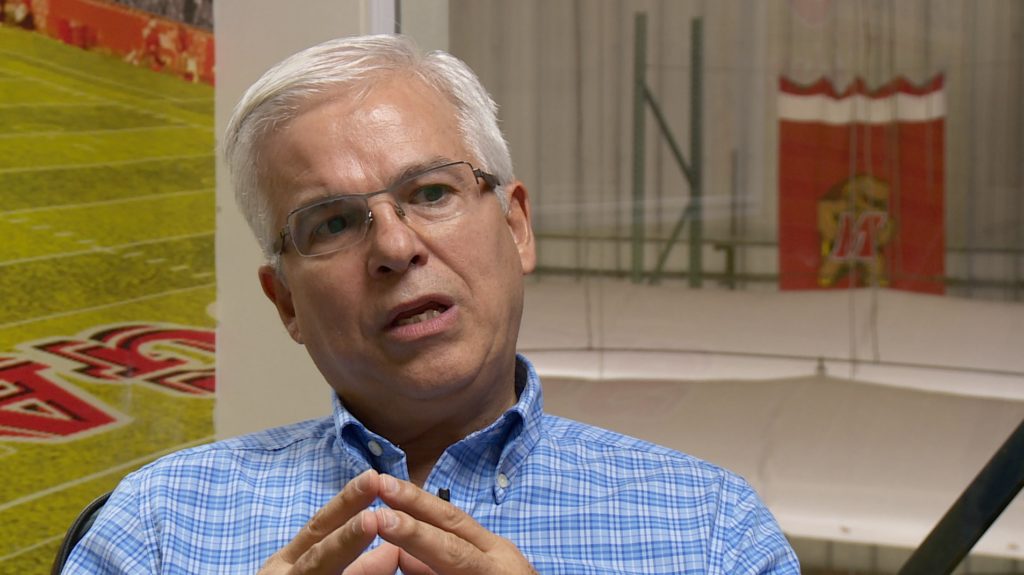

Rodrigo Bolanos:

Now, only if you have an educated population, you can do something for this country.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

And you don’t right now?

Rodrigo Bolanos:

Seventy percent of the population have not finished school.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

It’s one consequence of the brutal civil war in the 1980s from which El Salvador has never recovered; 75,000 people died. Many more were displaced. Many migrated to the U.S., and many of those deported back here have been responsible for escalating gang violence that has given this country the world’s highest homicide rate.

Rodrigo Bolanos:

We are one of the few being left behind. We have to, as a country, unite and put a plan together just the way we’re doing it here. I’m working with the community to make sure that all the kids end up in college.

We offer English every an half-hour.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

About a fifth of the 550 workers at this League sportswear factory are high school dropouts, a gap in their education that Bolanos demands they fix if they want to keep their jobs. Failure to get their high school equivalency degree draws a stern lecture and a not-too-subtle threat.

Rodrigo Bolanos:

If you don’t study, this is not the place for you. You have to study.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Bolanos often brings back those he’s fired if they make a new commitment to study. People deserve a second chance, he says, or a first. His work force is a cross-section of the unlikeliest hires for a factory job in El Salvador.

Francisco Escalante (through interpreter):

In this country, it’s hard to find a job, especially when you have a disability. Nobody will hire you.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Twenty-seven-year old Francisco Escalante is among two dozen disabled workers here. Blind since he was a 8 years old, Escalante works in the quality control lab. His fingers, sensitized by reading braille, are ideally suited to detect any imperfection in the millions of feet of fabric.

Francisco Escalante (through interpreter):

It’s most important that the cloth is as smooth as possible. There are five different categories that I have to check in order to certify that the cloth is up to standard.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Another category of workers are former gang members, identifiable by their trademark tattoos and unemployable most places because of them; 39-year-old Carlos Arguetta says he was a leader in the notorious MS-13 gang, but gave up gang life when he joined an evangelical church.

He told me that when he heard League Outfitters was hiring, he hid his elaborate body art for the job interview.

Carlos Arguetta (through interpreter):

Mr. Bolanos said, “Why are you dressed with long sleeves? Do you have tattoos?” And I said yes. And he said, “Don’t worry about that anymore. That’s your past. Now you have to start thinking about your future.”

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Arguetta now works security during the day, and takes intensive English classes in the plant at night. He dreams that someday he will own his own business, but, for now, is grateful for the job he has.

Carlos Arguetta (through interpreter):

If I didn’t have a job like this one, I would probably still be part of the gang and be doing killings. I want to send the message that we need these kind of opportunities. We need prevention programs. That’s what this country needs.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Another former gang member, Oswaldo Henriquez, was with a rival group, the 18th Street gang.

Oswaldo Henriquez (through interpreter):

I cannot tell you where I would be if I hadn’t gotten the chance to work here.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

He is now in his second year of college, studying mechanical engineering. The two-year college is located inside the factory walls and is affiliated with the University of Don Bosco. Bolanos says he got the idea while in Houston, Texas, where he studied engineering.

Rodrigo Bolanos:

I saw the American dream, where lower- and middle-class kids can work and study at night in community colleges. And for me, that is a good way to resolve and to give the American dream right here in El Salvador to all these poor people.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Four years ago, Bolanos created a new pipeline to get employees into this unusual garment factory college. He teamed up with a nearby school, promising every student who graduates a job in the factory by day, and college by night. The idea is to give these young people an incentive to finish high school, instead of dropping out and joining a gang.

At their school, heavily armed soldiers patrol to keep gang recruiters at bay. Principal Davidos Sandoval says the partnership with League Outfitters has transformed the school.

Davidos Sandoval (through interpreter):

Before we had the relationship, we had a 36 percent dropout rate. And now nobody drops out. League gives the students an opportunity to keep dreaming about their future.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Rodrigo Bolanos keeps dreaming as well. He’s begun several start-up companies within the garment factory to tap the higher skills being acquired by his newly college-educated workers.

Rodrigo Bolanos:

He used to work as a sewer on the floor. And now he’s repairing boards.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

If El Salvador is to join the 21st century economy, he says, it needs to create 21st century jobs, and provide them to all its citizens.

For the PBS NewsHour, I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro in Ciudad Arce, El Salvador.

William Brangham:

Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

From Gangs to Garments

At this garment factory that makes T-shirts bearing the logos of American universities, about a fifth of the workers are high-school dropouts. But if they want to keep their jobs, they’ll need to do something about it. Special correspondent Fred De Sam Lazaro reports from El Salvador on the factory turned college pipeline that employs those normally left out of society, including ex-gang members.

Rodrigo Bolanos

A Devastating History

El Salvador’s current state is a consequence of the brutal civil war in the 1980s from which El Salvador has never recovered; 75,000 people died. Many more were displaced.