Judy Woodruff:

In the Navajo Nation, many residents still live off the grid, making it challenging to live their day-to-day lives.

Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro recently traveled to the sprawling reservation, which is spread across parts of New Mexico, Arizona and Utah.

It’s part of our weekly segment on the Leading Edge of science and technology.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Neighbors and visitors are few and far between in much of the Navajo Nation in Northeastern Arizona.

So, Grace White was especially happy to get a recent visit from Melissa Parrish (ph), who works for the Navajo electric utility; 75-year-old White survives and even speaks, much like her ancestors did, living in a mud hogan, with neither electricity nor running water.

Grace White (through translator):

I use kerosene for lighting and wood to heat my home. Fresh food doesn’t last more than a day or two. So, for meat, I dry it in the sun to make jerky.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

For more than 60 years, she and her family have tried to get connected to the electrical grid. They have even built a more modern building on their homestead with light fixtures and electrical outlets just waiting to be hooked up. But it would cost more than $40,000 to do so. That’s money she doesn’t have.

One-third of the homes in Navajo Nation, about 18,000 of them, have no access to grid electricity. Back in the 1930s and ’40s, the federal government provided loans to utilities to connect rural and remote areas to the grid under the Rural Electrification Act.

However, the Navajo Nation, like many reservations, was bypassed. Utilities didn’t typically serve Native lands and opted not to expand into them. The irony is that the Navajo Nation is a huge exporter of electricity. The biggest coal-fired plant west of the Mississippi is located here, churning out power that is sold to millions of customers in Arizona, Nevada and California.

What the Navajo Nation did get from the plant and a coal mine that fed it is employment, more than 1,000 jobs. But now even that could soon be lost. The plant’s Phoenix-based owners plan to shut it down next year.

LoRenzo Bates:

It’s challenging and it’s frustrating.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Navajo Council speaker LoRenzo Bates says the unemployment rate as it is, is 50 percent on the reservation, which stands to lose not only the jobs, but many people who held them.

LoRenzo Bates:

It’s either take a transfer or you’re out of a job. The breadwinners of the family are literally forced to go someplace else to work.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

He says the mine and power plant pay some $30 million to $40 million in annual taxes and royalties, which are needed by the tribe.

LoRenzo Bates:

Youth programs, any social services.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Tribal leaders are trying to find a buyer for the plant to avoid the shut down. It won’t be easy. Many energy experts, including the plant’s current owners, say cleaner burning natural gas is cheaper than coal. Others see a new opportunity.

With its wide-open, windblown spaces and abundant sunshine, many here in Navajo country see the solution to its energy needs in renewables. And the first major installment in the direction is called the Kayenta Solar Project, a massive array of collectors that’s big enough to power at least 13,000 homes.

Plans are already under way to double the size of this array, and within five years, it is expected to generate nearly the same amount of power as the Navajo generating station.

Twenty-three-year-old Tasi Malala says solar is the only way forward. He helped build the this solar field, which also launched his career.

Tasi Malala:

I learned everything from the bottom up, from the piles in the ground to installing the hardware, managing my own crew, to actually setting up communications here that go back to the control center.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Nearly 300 people were employed during the construction of the solar array. Most of them, like Tasi Malala, were Navajo.

Tasi Malala:

Having these jobs open up, it’s really opening a lot more doors for the younger generation, kids or even people in high school.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

However, once construction was done, few jobs remained. Tasi Malala was hired by the company that built this array. But much of his work is off the reservation, from South Carolina to Georgia and now California, working on new installations.

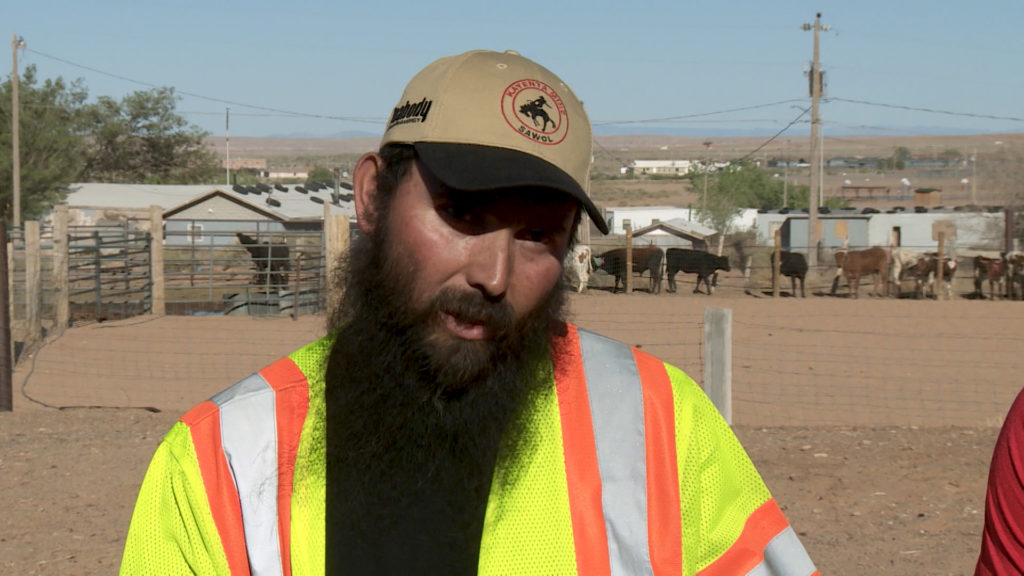

And that’s the problem that Tasi’s father, George Malala, has with renewables. He says coal has been a reliable source of energy and stability.

George Malala:

For me, coal is long-term years of employment. It employs a lot of people, compared to natural gas and solar.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

He is a mechanic in the coal mine which will likely close down with the power plant, tearing apart community and lifestyle, in his case, the popular hobby of rodeo.

George Malala:

It’s family that is going to break up. Won’t be nothing but ghost towns, you know? We have seen it through history.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

There’s a classic generational divide here. Coal has brought a good living to the father. Solar promises a good one to his son.

But few people argue with protesting employees and their supporters that nothing could soon replace the economic impact of the Navajo generating station. But large solar fields won’t bring electricity to people living far from the grid. So the tribal utility has begun installing off-grid home units.

About 3,000 panels have been installed so far, but the utility’s resources are limited and many more families are on the waiting list; 78-year-old Glenda Ashley recalls what it was like to live without a refrigerator.

Glenda Ashley:

We bought meat. We had the old refrigerator out there, freezer, and we would leave it out there for overnight, because it was colder out there.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

But you couldn’t store meat for more than a night?

Glenda Ashley:

Oh, no, no.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Six years ago, she got an off-grid solar system that now powers a refrigerator. It has brought convenience and huge savings from fewer trips to the grocery store. The nearest one is a 45-minute drive

Glenda Ashley:

It really is a help.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

She still needs to conserve to keep the appliance going. Too many lights on or too much TV could drain the limited power stored in the unit’s batteries.

Limited as it is, an off-grid system would be a huge improvement for Grace White. But the utility’s Parrish could only promise she’d be back soon, no fixed dates, with a solar installation. It could be months or even years away.

For the “PBS NewsHour,” I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro in the Navajo Nation.

Judy Woodruff:

Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

The coal economy brings jobs

Bypassed in the ‘30s and ’40s, one third of homes in Navajo Nation still have no access to grid electricity. Yet ironically, it’s a huge electricity exporter, with one of the biggest coal-fired plants churning out power sold to millions. And now a plan to shut down the plant could sorely cost the reservation. Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports that some are seeing a new opportunity.

Kayenta Solar Project

This massive array of collectors that’s big enough to power at least 13,000 homes is the first major solar installment in the Navajo Nation, but plans are underway to double its size.

Point of View

“Having these jobs open up, it’s really opening a lot more doors for the younger generation, kids or even people in high school.

Point of View

“For me, coal is long-term years of employment. It employs a lot of people, compared to natural gas and solar. … It’s family that is going to break up. Won’t be nothing but ghost towns, you know? We have seen it through history.”

Off-Grid Solar

For the Navajo Nation’s off-grid residents, the promise of solar means food preservation through refrigeration, lights at night and much more.