Judy Woodruff:

But first, across the continent of Africa, a brain drain sends many of its highest-skilled professionals abroad.

But as Fred de Sam Lazaro reports from Uganda, one organization is trying to build a pipeline to keep medical professionals working in their native country.

It’s part of Fred’s series Agents for Change.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

This class of 30 soon-to-be nurse midwives are training in Lira in Northern Uganda, a new university set up to address this country’s severe shortage of trained medical professionals.

Key members of the faculty are American volunteers with a program called Seed Global Health. Over the past five years, it has sent 184 medical professionals to five African countries, training nearly 14,000 students.

Emergency room physician Vanessa Kerry founded the nonprofit.

Dr. Vanessa Kerry:

If you look at sub-Saharan Africa, it has 24 percent of the world’s global burden of disease, and only 3 percent of the world health care work force with which to address that disease. That’s a huge disparity.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Kerry, who is the daughter of former Secretary of State John Kerry, first became interested in global health as a teenager, when her father, then a senator, took her to Vietnam.

Dr. Vanessa Kerry:

That trip was game-changing for me, I mean, just the absence of resources, no electricity, no running water, no shoes on kids.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

In 2012, some two decades later, with degrees in medicine and public health, she founded Seed in partnership with the Peace Corps, sending U.S. doctors, nurses and midwives for one-year stints in rural Africa.

Midwife Linda Jacobson from Olympia, Washington, served a year in Tanzania and is now Uganda conducting specialized seminars.

Linda Jacobson:

There’s incredible satisfaction about making what would be a small difference in the United States is a huge — can make a huge difference in the lives of women and babies in these settings.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

The curriculum, the first to offer bachelor’s degrees, is meant to radically upgrade the way nursing is perceived and practiced in Uganda to revive a profession that currently gets little respect and resources, with predictable results, says Okaka Dokotum, deputy vice chancellor of Lira University.

Okaka Dokotum:

You have mothers who die in childbirth because of neglect or nurses were late. There is lack of kindness. And I see that — a lack of professionalism. It’s an ethical issue.

And over and over, we talk to our students and say, we want you to do something different.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Third-year student Patience Nafulla says the clinical experience has already given her a fulfilling experience, recalling one new mother’s deep gratitude after a difficult delivery.

Patience Nafulla:

I talked her through it. When I came back the following day, she knelt down for me. She knelt.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

She knelt down before you.

Patience Nafulla:

That really touched me. And I knew from that moment I can make a difference.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

The emerging crop of nurses and midwives have been trained under conditions that would be considered normal in the West or in private clinics here, things like access to clean water, stable electricity, adequate supplies.

The problem is, these basics are far from guaranteed in much of the workplace they’re going into, especially in rural areas.

Lira University’s Dokotum does worry that Uganda’s public health system is not yet fully equipped to absorb the new highly skilled graduates.

Okaka Dokotum:

It’s like having a Ferrari and then just going at 20 kilometers per hour, you know? So it’s going to take changing policy. We will have to try to influence policy to make sure that room is created for this new coterie of nurses and midwives.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

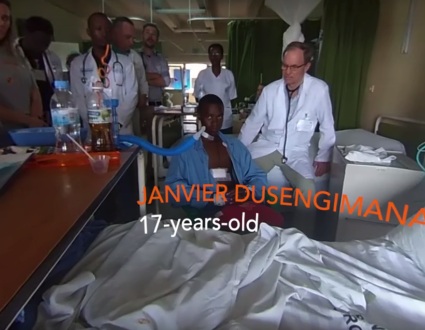

Geoffrey Odong would certainly like to see that policy change. The recent graduate from the Seed program is interning at a public hospital and says he often feels resented for his higher-level skills. He’s allowed mostly to just observe, he complains.

Geoffrey Odong:

What we’re trained on, we are not being allowed to practice.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

So you could be doing much more than you are doing?

Geoffrey Odong:

Absolutely.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

For its part, the Seed Global Health program faces a threat of its own. The Peace Corps recently announced it would exit starting this fall, citing a change in its approach to such partnerships. The Corps declined our request for an interview.

Dr. Vanessa Kerry:

I’m really, really proud of what we have done. And I am frustrated.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Dr. Kerry blames the Peace Corps decision politics and says the resulting cutbacks will force a significant scaling back from five countries to two, including Uganda, and far fewer American medical volunteers.

Dr. Vanessa Kerry:

There’s been I think, a real concern, around global health funding, a worry that global health funding is going to be at risk.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

As she and colleagues regroup and seek other funding, Uganda’ health care system must contend with a different kind of threat, poaching.

Well-trained nurses are in high demand in the West, Middle East, Gulf states and elsewhere in Africa, where salaries and working conditions are far better than in Uganda.

As university officials and advocates work to improve conditions here, students, such as Patience Nafulla, face a fraught personal dilemma.

Patience Nafulla:

I prefer being here. If we have everyone go out, who will then stay to help our country? The temptation is there. There is better pay. The resources are there. Why not go? Why stay? So, that’s the challenge.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

The challenge for Uganda will be to improve its health care system and coax students like these to stay and work here, particularly in rural areas.

It’s estimated that one of every four midwife positions in the public health system is unfilled.

For the “PBS NewsHour,” I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro in Lira, Uganda.

Judy Woodruff:

Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

Better Facilities and Pay

A “brain drain” is sending many of Africa’s highly skilled workers abroad–and leaving a painful void in their absence. But an organization called Seed Global Health is training new medical professionals and encouraging them to remain in their native countries, where they are so desperately needed. Fred de Sam Lazaro reports from Uganda as part of his series Agents for Change.

A Pressing Need

It’s estimated that one of every four midwife positions in Uganda’s public health system is unfilled.