Judy Woodruff:

Every year, nearly half-a-million people die from malaria across the globe. Though there are drugs available to kill the parasite that causes malaria, there is new worry that those medications are losing their effectiveness.

Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports from Cambodia.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Few Cambodians have a tougher commute to work than Chrab Prey. The 27-year-old malaria worker must wade knee-deep across a stream, keeping her treated bed nets dry, before reaching her motorcycle.

Chrab Prey:

Sometimes it’s very flooded, and I have to swim across the water.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Once on her motorbike, she tries to reach an elusive population of migrants she calls mobile workers, deep in the remote forest here in Western Cambodia.

Chrab Prey:

Sometimes, I cannot find the mobile workers, because they are working. And I can’t call them because there is no cell service. So that is difficult.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Often, it is only after the symptoms, like a severe fever or headache, become unbearable, that people themselves come out of the forest to seek help.

That’s what happened to Rat Sophat, who is now back at the job she loves as a hairstylist in her village. Two weeks after being treated for malaria, she still suffers from some effects.

Rat Sophat:

After taking the medicine for two weeks, I still have the chills. I’m not really recovered yet.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Rat was caught up in a surge in malaria that began in mid-2017, a year when infections nearly doubled to some 45,000. She contracted the mosquito-borne illness while working on a logging team deep in the forest.

Like Rat, the vast majority of cases respond to treatment. But scientists fear that it’s in this remote area along the Thai border that they could lose the battle to contain the malaria parasite.

About a decade ago here in Cambodia, scientists began to see cases in which the deadliest form of the malaria parasite had mutated and become resistant to the last available drugs that could fight it. That resistant strain has since spread, with cases in Thailand and Southern Vietnam.

It raises the possibility of a resurgence of resistant malaria that scientists fear could spread far beyond Southeast Asia.

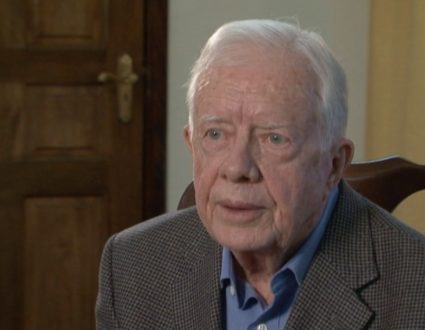

Arjen Dondorp:

And if it reaches Africa, it can kill millions of African children.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

It’s happened before, says Arjen Dondorp, who directs a major malaria research effort in neighboring Thailand.

Back in the ’80s, resistance to the widely used drug chloroquine developed here in Asia and quickly spread to Africa, where treatment is less readily available, resulting in a huge spike in malaria deaths.

New drugs have since contained the parasite, which has been wiped out in much of the Mekong region, but there remain hard-to-reach pockets.

Arjen Dondorp:

Malaria is a disease of marginalized populations, often living in border areas, very remote, difficult to reach.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

That’s where malaria workers come in.

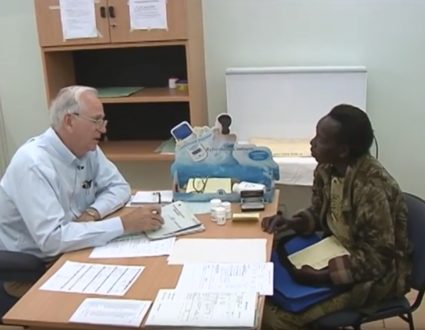

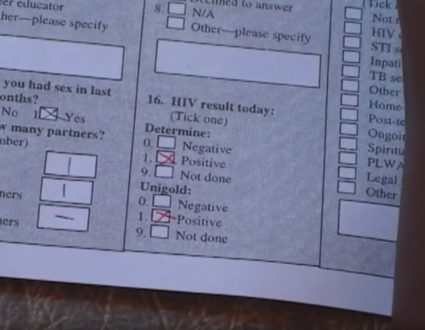

In her village, Rat Sophat got a follow-up call from Soksam Sambath, who confirmed that, even though she still had symptoms, she doesn’t have the resistant malaria stream; 61-year-old Soksam actually makes his living selling fried banana chips, but, 15 years ago, he received training to detect, treat and educate his fellow villagers about malaria.

Soksam Sambath:

My job is to go around the community to help people. I don’t have a salary. They pay me for transportation and on the days when I see people. The pay is small, but I think this job is important, because I can help people. That’s why I do it.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Soksam is part of a pilot program in three provinces of Cambodia funded in large part by a program started during the George W. Bush administration called the President’s Malaria Initiative.

In this region, the money funds community malaria workers, as well as a rapid detection and reporting program to track and contain outbreaks, especially any cases that do not respond to drugs.

In the pilot project areas where migrant farmworkers like these are key target, project manager Rida Slot says the coordinated approach has shown promising results.

Rida Slot:

Despite the intensified resistance to malaria treatment, the country has successfully reduced malaria transmissions. And then we are proud to say that they’re moving toward malaria elimination.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

But it’s in the so-called last mile in the forest that the danger of a drug-resistant outbreak is greatest. Roads, where they exist, aren’t always passable, and people, many engaged in illegal logging, not eager to see anyone that seems official.

Sharon Thamgadurai:

The moment they see some of the government functionaries or officials or partners moving in, talking to them, they feel fearful, because they are in a location where they are not supposed to be.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Sharon Thangadurai leads the U.S. effort in Cambodia.

Sharon Thamgadurai:

They don’t want to actually get themselves recognized, you know? So these are some of the major challenges that we face.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

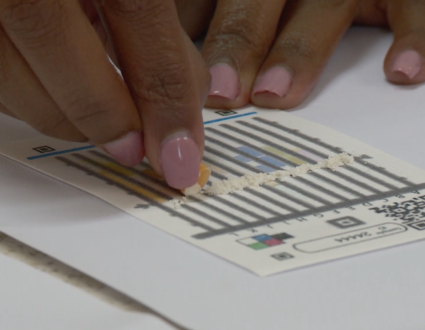

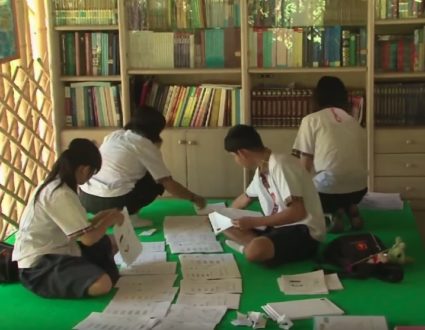

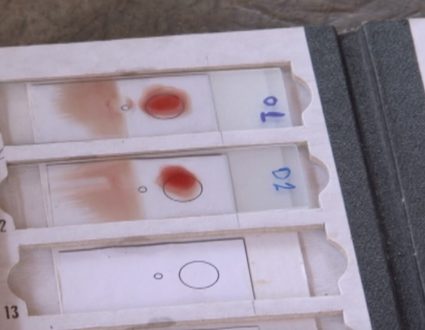

At the edge of the forest where migrant workers transit in or out, malaria worker Chrab tries to present a non-threatening official presence. She informs people about available resources, offers bed nets, and also randomly tests about 20 people each month, looking for those who might not yet show symptoms, but carry low levels of the parasite.

Despite these efforts, she guesses that she will never come in contact with at least a quarter of the workers in her area of the forest. Nonetheless, malaria campaign officials say the approach is bringing down infections here in the pilot region.

And they’d like to see it implemented elsewhere where malaria cases have been on the rise.

Dr. Nick White:

This was 1982. This was manufactured in China. You can see this is one of the first vials made.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Dr. Nicholas White, one of the world’s leading experts on malaria, says he’d like to see even more done about a disease that he says is often not a priority.

Dr. Nick White:

Almost, if you like, a military approach. It would require considerable coordination between countries, such things as border checks, much more active use of mass drug administration, which is a crude, but effective tool.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

The Geneva-based Global Fund Against AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria recently announced grants for government and non-government agencies to contain, even eliminate malaria in the great Mekong region.

But Dr. White says, with daunting geographic and political hurdles, that prospect can sometimes seem as remote as the villagers where malaria lurks.

For the “PBS NewsHour,” I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro in Pailin, Cambodia.

Judy Woodruff:

Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

Researching & Tracking

Malaria causes nearly half a million deaths worldwide every year. Ninety percent of them are in sub-Saharan Africa, where poor infrastructure limits delivery of drugs. But now there is worry that those drugs are losing effectiveness as disease strains become resistant. Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports from Cambodia, where scientists are researching and tracking new outbreaks.

Migrant farmworkers are a key target

At the edge of the forest where migrant workers transit in or out, malaria worker Chrab tries to present a non-threatening official presence. She informs people about available resources, offers bed nets, and also randomly tests about 20 people each month, looking for those who might not yet show symptoms, but carry low levels of the parasite.