Judy Woodruff:

Deadly viruses often fester inside animals in before they move into human populations.

One project in Northern Thailand is using technology to try to stop outbreaks before they start.

Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports as part of our Breakthrough series on innovation and today’s story on the Leading Edge of science and medicine.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

There are more chickens than people in remote Thai villages like Huay Ton Chok, and people do worry when their chickens stop crossing the road.

That’s because, five years ago, this village suffered an outbreak of flu-like disease that killed hundreds of birds. So when farmer Udom Putipatharakal thought one of his chickens wasn’t doing well and another looked really ill, he reported it.

Udom Putipatharakal:

We still have a small number of chicken deaths, so we don’t know what to do.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

For four years, Pariwat Roomak has been dispatched from the local health department, responding to calls about sick animals in the area.

Pariwat Roomak:

I take photos of the chicken. I look to see if there are any abnormal feces. And I also ask neighboring Households If they have had any dead chickens.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

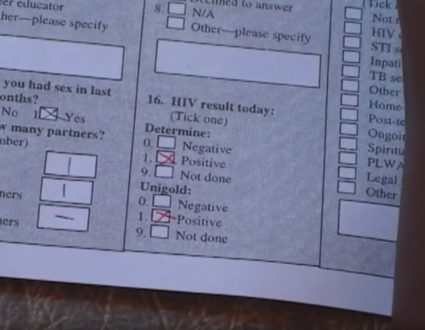

Pariwat enters all of this information into an app on his smartphone and transmits it directly to the local government health office, the veterinary department and to a major university to be analyzed.

It’s part of a participatory One Health disease detection program, more simply called PODD. And it has become a model for programs like this all over the world. It’s villages like this one that scientists fear could be the cradle of the next superbug, one that can jump from animal to human, and then mutate so it can leap from human to human.

So the objective of this exercise is to track every diseased animal, particularly chickens, so as to contain an outbreak before it becomes a pandemic.

Dr. Mark Smolinski:

HIV, MERS, SARS, Zika, all of these things. Ebola.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

They all began in animals, says Dr. Mark Smolinski. He heads a San Francisco-based nonprofit called Ending Pandemics that is funding the program in Thailand. He described one possible scenario of how a farm like Udom’s could become a petri dish.

Dr. Mark Smolinski:

A pig has receptors for both bird flu and receptors for human flu.

So when we have a farmer who has a sick chicken who also has pigs and other animals on the farm, who may have a family member with influenza, if that pig were to get human influenza that we know spreads very quickly, if that were to cross over because that pig was also infected with the bird flu on that same farm, then that resulting could be the pathogen that we’re all worried about.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

A pathogen that could now jump back from pig to human and, critically, human to human.

Farmer Udom says his pigs are doing fine, only chickens have fallen ill, and nothing like six years ago, when dozens of households reported diseased birds and many areas had to be disinfected. This village was particularly hard-hit.

Udom Putipatharakal:

All the chickens in the village died. Now the problem is different. Not as many chickens are dying, but still one dies every day or every other day.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

The new system allows for swift response when any disease afflicts any domesticated animal.

Jaruwan Chaichom heads the local health department for this region.

Jarwan Chaicom:

Before we adopted the system, the villagers didn’t have a way to connect with each other or with us. The local government is quite far away from them. Language is another barrier, because we have seven ethnic groups and seven languages in this area.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

A smartphone app developed for the program translates those languages, so all the responders can track where the diseases are occurring.

Patipat Susumpow leads the firm that designed the app. It had to be simple, he says.

Patipat Susumpow:

The penetration rate of smartphone is not really high in those communities. So most of our volunteers either never used a phone before or used like a very simple phone.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

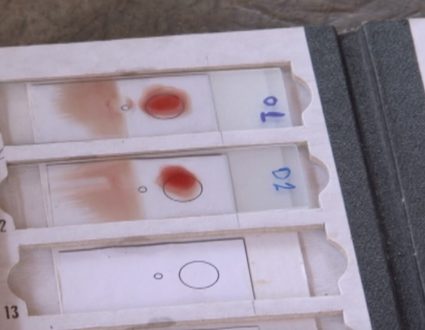

Next stop for the diseased bird, a two-hour bus ride to Chiang Mai University.

Here, scientists determine the type of disease, the likely cause, and, accordingly, recommend action to prevent its spread, whether it’s administering antibiotics to animals or disinfectant spraying.

At first, there was some resistance to the new system. Villagers feared for their livelihood. Local health officials feared an increase in reporting might reflect poorly on their management practices.

But Dr. Smolinski said those concerns disappeared in these remote communities early in the 4-year-old program when a health worker reported a case of hoof-and-mouth disease.

Dr. Mark Smolinski:

By her reporting that one single cow, they were able to rally local resources and do a vaccination campaign, and that saved $4 million for that village, because they would have been banned for exporting their milk for an extended period of time until all of that disease was gone.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Tech developer Patipat says the tool is spawning new ideas to improve life in communities. It’s also being for alerts about criminal activity, food safety issues and natural disasters.

Patipat Susumpow:

We hope the app can be the placeholder for democratizing the power of response and disease management back to the community.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

But not every community or country is ready to sign up. Some fear driving away tourists. Other countries are beset by conflict or weak governance.

Dr. Smolinski says recent epidemics have shown the cost of inaction.

Dr. Mark Smolinski:

Ebola in 2014 that led to 11,000 deaths, it was an eight-month delay before we knew that was Ebola. We wouldn’t have that delay if that community would have been able to send some signal that something’s not right.

They might not have known it was Ebola, but that kind of signal, where we see that there’s a cluster of fevers coming out of one particular geographical area in a very short time frame, we know there’s some acute event going on.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

The silver lining from tragedies like the Ebola epidemic, he says, is that it’s driven home the value of surveillance and swift intervention. And Smolinski says his group has been invited to pilot its project in 35 countries.

For the “PBS NewsHour,” I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

Judy Woodruff:

Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

Disease Containment

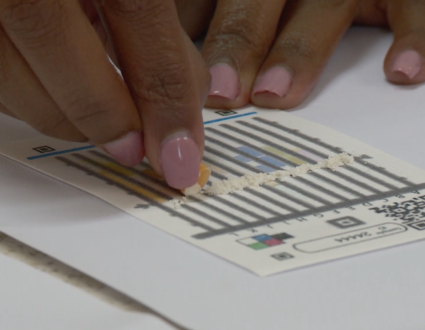

Viruses like Avian flu, Ebola and Marburg often fester in animals before moving into human populations. Animals in regions that are geographically remote present particular challenges for disease containment. But in Thailand, local residents are using technology, including digital scanning, to track animals and stop outbreaks before they start. Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports.

Huay Ton Chok

It’s villages like this one that scientists fear could be the cradle of the next superbug, one that can jump from animal to human, and then mutate so it can leap from human to human.

Mobile Technology in the Field

Disease trackers transmit photos, location and any other information directly to the local government health office, the veterinary department and to a major university to be analyzed using a smartphone app