Judy Woodruff:

Rheumatic heart disease, a condition that afflicts more than 30 million people globally, kills an estimated 300,000 every year, most of them young people in developing countries.

Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports on one group trying to make a dent in Rwanda.

It’s part of Fred’s series agents for change.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

It is an extraordinary reunion, held once a year in Rwanda’s capital.

Woman:

You feeling well? You’re feeling healthy?

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Nearly 200 people came together. Almost all of them would be dead from a serious heart condition, if it weren’t for surgery they got through the project they came to celebrate.

They’re all survivors of rheumatic heart disease, a condition that’s caused by untreated strep throat, an infection that is routinely treated in developed countries with antibiotics like penicillin.

Dr. Chip Bolman:

But in places like Rwanda, they don’t get treated, so this eventually turns into rheumatic heart disease. Over time, the valves become infected. They either become narrowed so that the blood can’t get through them, or they don’t close properly. Both of them can result in very severe heart failure and death, premature death, if not treated.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Overwhelmingly, Dr. Chip Bolman says, that’s what happens in a country that has only five cardiologists and no heart surgeons for a population of 12 million.

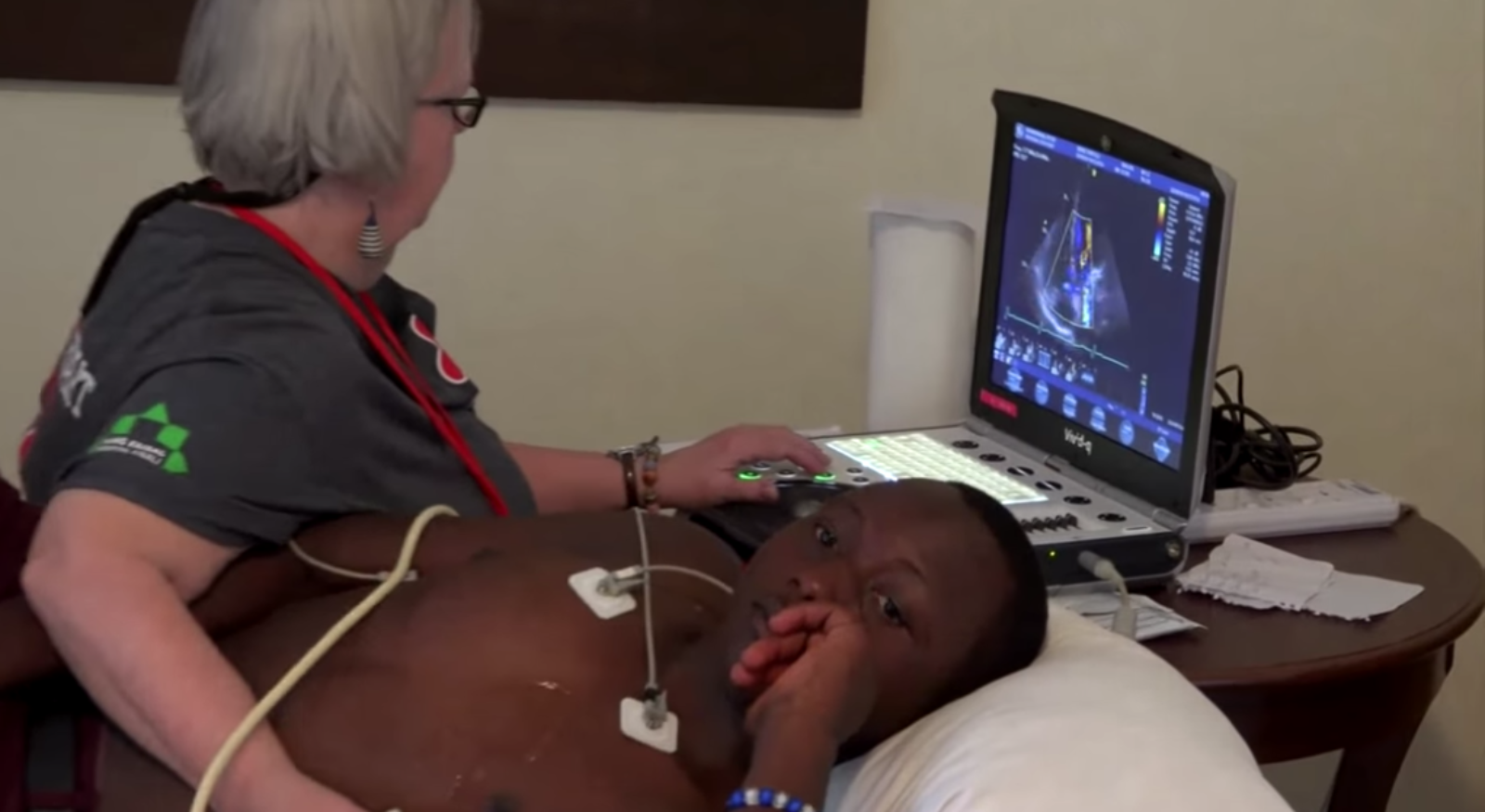

Bolman is an American heart surgeon and, with his wife, an intensive care nurse, started a nonprofit called Team Heart 11 years ago. They wanted to draw attention to a condition that afflicts someone million young people across sub-Saharan Africa.

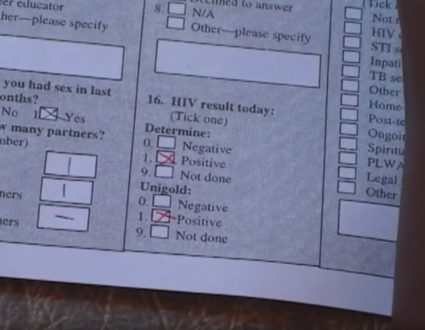

Once a year, a large volunteer surgical team arrives in Rwanda and sets up in Kigali’s King Faisal Hospital for about three weeks. In that time, 16 lucky patients will undergo sophisticated open heart procedures. The best estimates are that some 30,000 young Rwandans suffer from rheumatic heart disease, so the 16 patients chosen for surgery have gotten here against lottery-like odds.

But their selection is far from random. The team’s meets the day before surgeries begin to reach the wrenching consensus for the 16 available slots.

Man:

I get the impression that there’s some aortic regurgitation here.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

There’s the case of 18-year old William. The doctors were on the fence.

Man:

He’s got such profound biventricular dysfunction, that I don’t think he’s a candidate for today.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

But surgeon Bruce Leavitt felt that, with medications, William’s heart might strengthen enough to undergo the deeply invasive heart valve repair.

Man:

He’s one guy that either one shot, or he doesn’t live.

Dr. Chip Bolman:

One of the most difficult aspects of this whole experience is that we do have to decide that some patients are not able to undergo this operation.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

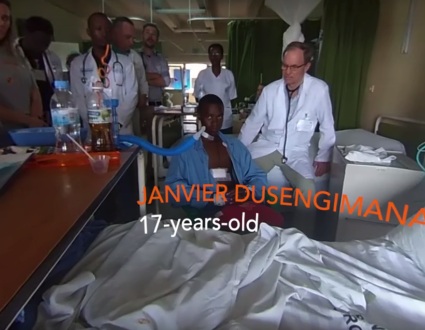

Seventeen-year-old Janvier Dusengimana was one of the lucky ones. For the last two years, his disease has been steadily crippling him.

Janvier Dusengimana (through translator):

When I tried to do any sort of work, especially lifting heavy things or farming, I would become weak. And I haven’t been doing anything, just sitting at home.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

He would soon go in for several hours of intricate surgery. The previous case, 16-year old Olive Mukeshimana, was just out of surgery and recovering in intensive care.

Like all the others, every aspect of her case and care was reported and deliberated. For her mother just outside, the wait was excruciating.

Caritas Mukeshimana (through translator):

It’s like when you’re in labor and you just go through the pain. You’re just hoping that the child will be born healthy.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

One day later, that’s how it turned out for Olive. Her graduation from intensive care to the recovery unit was marked by jubilant cheering.

Caritas Mukeshimana (through translator):

I am really, really happy and really thankful for everything that they have done for her.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Despite these successes, there are reminders of the vast unmet need. Remember William, whose case doctors wondered about at screening? In the end, his disease was deemed too far gone for surgery, a reminder to doctors of the limited options for patients here.

In the U.S. he may have been a transplant candidate, that is, if his disease ever progressed this far.

Dr. Chip Bolman:

We know almost with a certainty that if we had been able to see him two or three years ago, we could have saved him.

Dr. Marc Tischler:

This is just Rwanda. All of sub-Saharan Africa is suffering from the same thing.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Rwanda’s health minister, Diane Gashumba, says for years the government’s priority has been to deal with infectious diseases, like malaria, tuberculosis and HIV, what she calls the first killers.

Tackling noncommunicable diseases like diabetes and heart disease are only now getting some of the attention they need.

Dr. Diane Gashumba:

We have a shortage of doctors. And I’m happy that this partnership is really focusing on capacity building, turning doctors and nurses. So that is critical. And it gives hope when I see those young doctors, like Maurice.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Dr. Maurice Musoni has been mentored for years by Team Heart. He will complete his training in South Africa and return this spring as Rwanda’s first cardiothoracic surgeon.

Dr. Maurice Musoni:

It places a big responsibility on your shoulders. My biggest worry and challenge will be to transition from a situation that is well equipped to a situation where you have to do with whatever little you have.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

And Dr. Musoni will soon have an unlikely ally. Erneste Simpunga’s is the kind of happily-ever-after story the Bolmans wish they could tell about young William.

Ceeya Bolman:

He was really quite sick, very small, 17. He weighed 72 pounds.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

But he pursued her with irrepressible curiosity.

Ceeya Bolman:

He would ask me, “But if your husband could do my surgery, what would he do?”

And I would show him a diagram. And each day my heart would break a little bit, and I said, I don’t think I can leave him and not see him have surgery.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Thanks to a sponsor in Massachusetts, Erneste won the jackpot. He was flown to Boston and did have surgery.

Erneste Simpunga:

It’s been 10 years now. And I still hope to continue with further training and be able to contribute something to this long medical journey.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

That journey took him to medical school, an unexpected dividend, the Bolmans say, toward their eventual goal.

Ceeya Bolman:

We will not feel that we have accomplished what we set out to do until there’s a Rwandan surgeon at the table with a Rwandan anesthesiologist at the head of the table and the patients in the ICU taken care of by Rwandan ICU nurses.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

When he graduates this November, Dr. Erneste Simpunga plans to specialize in cardiology.

For the “PBS NewsHour,” this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Kigali, Rwanda.

Untreated strep throat causes an estimated 275,000 premature deaths per year

Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports on a medical team making the “wrenching” decision of which young lives to save.

The Lucky 16

With the limited time and resources at King Faisal Hospital, the team must make the wrenching choice of which patients they will operate on and which they won’t.