Judy Woodruff:

Eastern parts of Democratic Republic of Congo are struggling to contain the second worst outbreak of the deadly Ebola virus in history. Congo’s neighbors are on high alert.

From the border with Uganda, special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports for our Leading Edge series.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

This Red Cross outpost is Uganda’s front line in trying to contain the spillover of Ebola infections from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Every day, thousands of Congolese cross into Uganda, some fleeing violence and conflict, others simply coming to trade or shop. In the town of Kisoro, just inside Uganda near the border with Congo, is a typical market that could be anywhere in sub-Saharan Africa, a bustling free trade zone of fruits, vegetables, even flip-flops made from recycled tires.

It’s never felt like an international crossing for the locals, who don’t need passports or visas, and have come and gone freely. But now there’s a mandatory stop.

Ronald Kanyerezi:

And what we are doing right now is to emphasize the practical bit of it. That is hygiene promotion.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Hygiene promotion means Congolese visitors must now wash their hands in chlorinated water, decontaminate their feet and have their temperature taken before being allowed into Uganda, says the Red Cross’ Ronald Kanyerezi.

Those with high temperatures must rest for a while before a new reading is taken.

How often during the day do you have to quarantine people when you take their temperatures at the border points here?

Ronald Kanyerezi:

Sometimes, it can be like 10, 15. If the temperatures fail to go down, then we make a referral.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

A quarantine has been set up in a nearby hospital, he says, but, so far, thankfully, it hasn’t been needed. Ebola is spread by contact with bodily fluids from an infected person.

Uganda is no stranger to Ebola. In fact, prior to West Africa in 2014, the largest outbreak in history occurred here in the northern city of Gulu in the year 2000; 224 people lost their lives. That’s a little more than half of all who were actually infected.

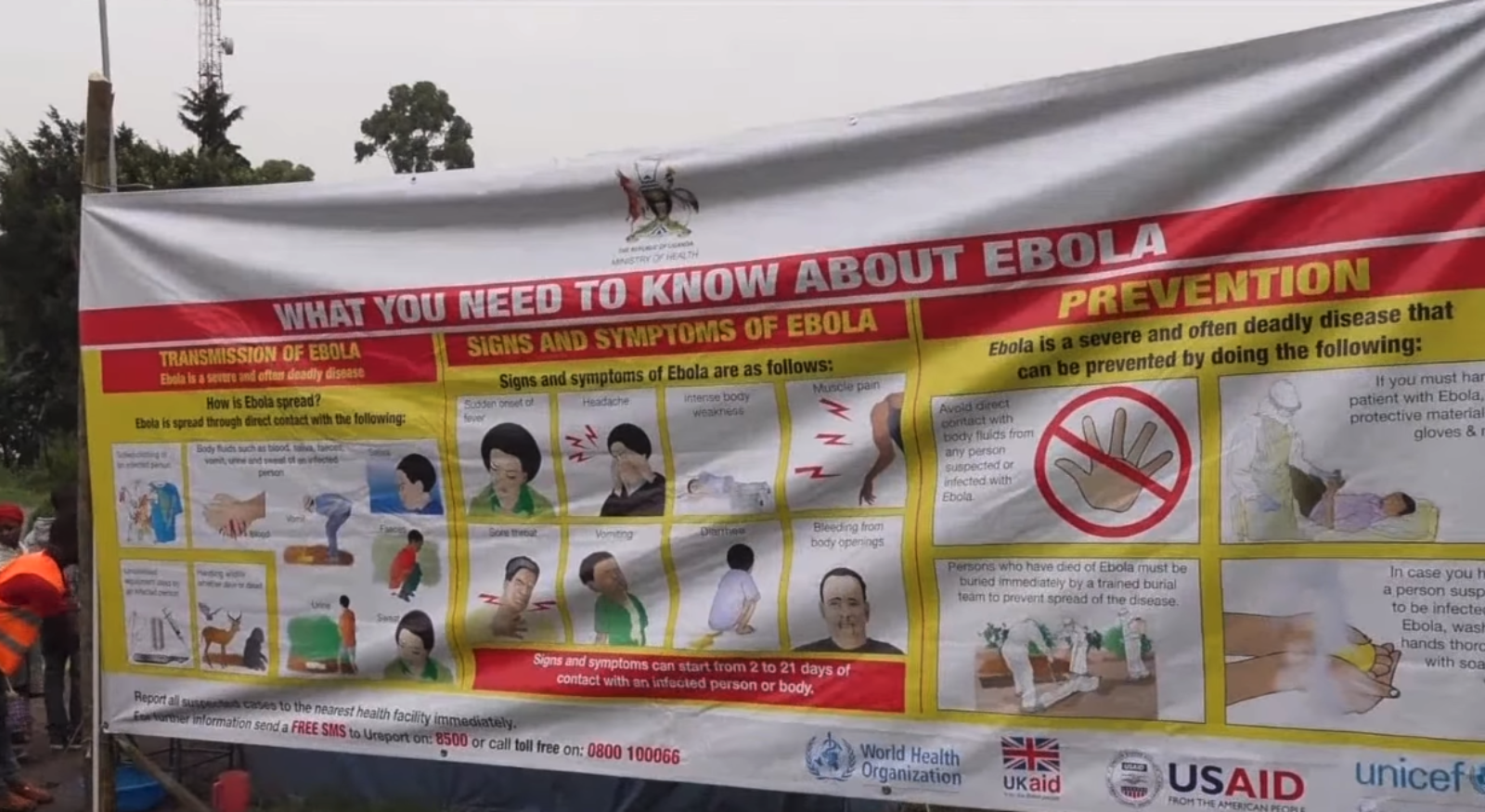

Besides border screening, there are information campaigns on the signs and symptoms of Ebola broadcast here in several local languages and dialects, and education posters throughout town. And there’s particular emphasis on isolated local communities, like the Batwa, or Pygmies, who communicate such messages through songs.

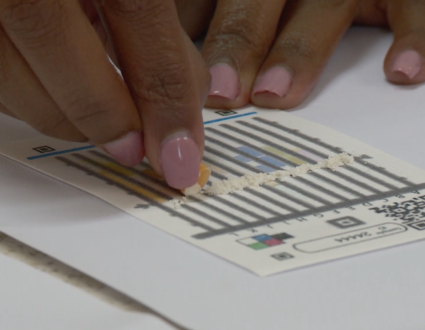

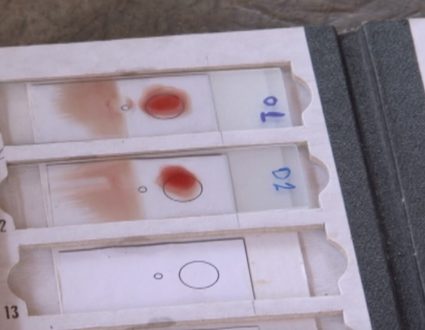

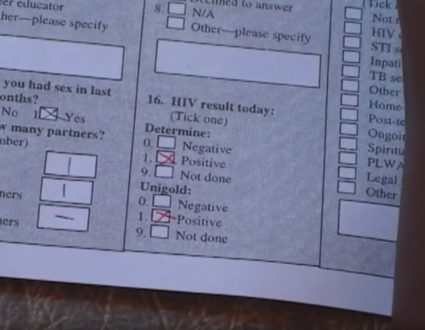

Uganda also has sophisticated lab facilities to quickly detect Ebola and closely related viruses, like Marburg, that cause severe hemorrhaging and high fevers.

John Kayiwa:

Any samples that are brought into this facility, they are quickly diagnosed at least within 24 hours. The result will be out and reported to minister of health.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

The lab has been on high alert since the outbreak began in August.

Kyondo Jackson:

This sample is negative.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

So you have been able to rule out Marburg and Ebola?

Kyondo Jackson:

Yes. We have ruled out.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

For the sample today?

Kyondo Jackson:

For the sample today.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Health officials near Bunagana and other border posts send in blood samples when a person has a persistent high fever and shows other signs.

This sample came from Hoima, near the DRC.

What would the patient have presented in terms of symptoms for them to have send this sample to you?

Kyondo Jackson:

Yes, they presented with a fever. Then he had diarrhea. Then he had nose bleeding.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

The sample was sent on to another lab to be tested for other less lethal infections like yellow fever.

This laboratory, in Entebbe, near Uganda’s capital, was set up by the Atlanta-based U.S. Centers for Disease Control in 2010, as part of an Obama administration effort to contain outbreaks.

Dr. Michael Osterholm:

That, to me, is one of the smartest investments we could make, setting up these kinds of laboratories and public health systems throughout the world.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Michael Osterholm is a public health and a biosecurity expert at the University of Minnesota.

Dr. Michael Osterholm:

For every dollar we spend on them, we will reap back, I believe, many, many dollars in return in terms of not having to fight a much larger problem that only gets caught after weeks and weeks of smoldering somewhere in the world.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

There’s also an Ebola vaccine that has shown some promise, he says. So far, about 80,000 people in the Democratic Republic of Congo have received it.

But for Congo’s neighbors, the emphasis remains on limiting infectious outbreaks.

Is there sufficient reporting and surveillance systems today so that these outbreaks, were they to spread into these countries, would be containable reasonably well?

Dr. Michael Osterholm:

I would have to say that all the planning that’s gone on to date and the pre-vaccination and the surveillance efforts, I would say we have a very high likelihood. Those areas are much more stable than their adjoining neighbor in DRC.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

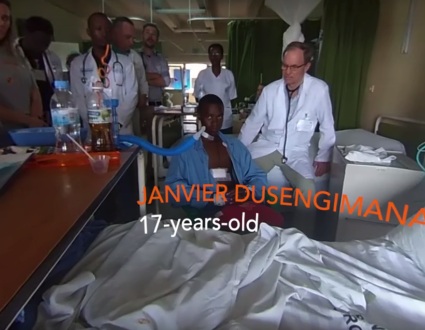

That instability in the war-torn Eastern DRC remains the big threat, as health workers struggle to vaccinate against Ebola and treat those infected.

If the virus spreads to larger cities, Osterholm says, the consequences could dwarf the West African pandemic of 2014. The hope here in border communities is that people will remain vigilant and on their toes.

For the “PBS NewsHour,” this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Bunagana, Uganda.

Judy Woodruff:

And Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

More than 500 dead

Eastern parts of Democratic Republic of Congo are suffering from the second-worst outbreak of the deadly Ebola virus in history. Neighboring Uganda is watching with concern as the crisis unfolds, wary of allowing Ebola to spread to its people. Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports on measures Uganda is taking at its borders in an effort to keep Ebola out.

A Public Information Campaign

Information campaigns on the signs and symptoms of Ebola broadcast here in several local languages and dialects and are on posters throughout town.

No Stranger to Ebola

Prior to West Africa in 2014, the largest outbreak in history occurred in Uganda’s northern city of Gulu; 224 people lost their lives. That’s a little more than half of all who were actually infected.