Amna Nawaz:How do you recover from a brutal war?As Uganda struggles to reconcile its violent past, education offers a glimmer of hope.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports on one effort to teach former child soldiers.It’s part of his series Agents for Change.

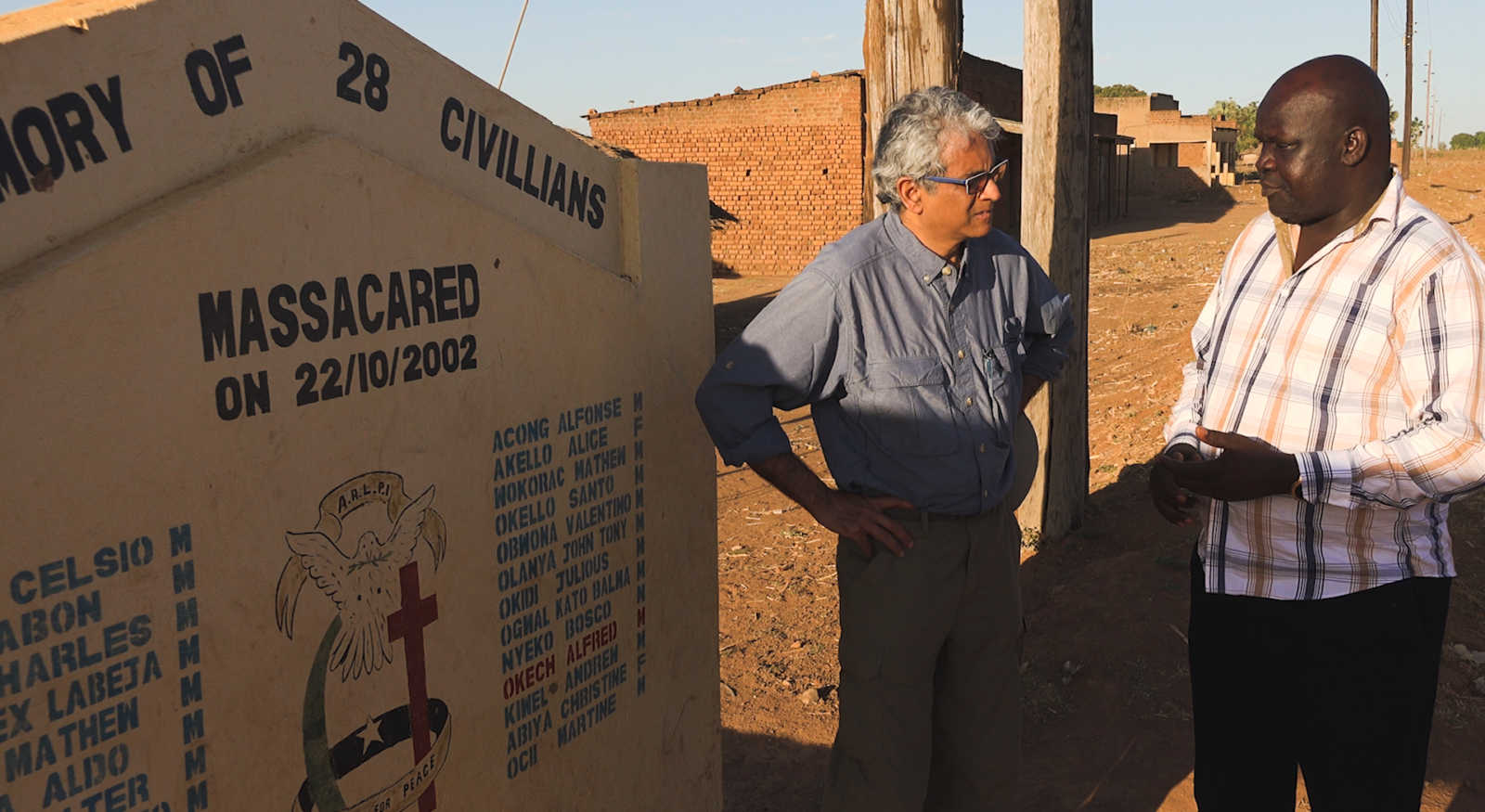

Fred de Sam Lazaro:The residents of the Lamunu, like many communities in this region, are trying to regain their rhythm to bring back some sense of normalcy with activities that have long defined community, like their 35-member dance club.For nearly three decades, this region was the epicenter of one of the most savagely violent conflicts in recent history. The Lord’s Resistance Army, or LRA, was led by Joseph Kony, who called himself a spokesman for God.The LRA’s goal was to overthrow Uganda’s government, a campaign that displaced close to two million people. As many as 35,000 children were abducted, deployed as servants, sex slaves and soldiers.Out of a landscape that still looks full of rubble, still shattered from years of conflict, a monument to the lives of 28 civilians who were massacred here in 2002, 28 out of an estimated 100,000 civilians who lost their lives.

Ricky Richard Anywar:I can still remember that clearly the day I was abducted.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Ricky Richard Anywar was 14 when he was abducted alongside his older brother.

Ricky Richard Anywar:These people rounded up our family members and set them ablaze while we are watching. They close the door, and they set the fire ablaze while they were asking for mercy. It was the darkest moment in my life.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Horrific as that sounds, it was far from the most brutal incidents.

Ricky Richard Anywar:This is one of the saddest massacres in Northern Uganda, the way our people were cooked in the pot, and people…

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Cooked in a pot?

Ricky Richard Anywar:Yes.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Anywar was among the lucky few who managed to escape, returning to his native town of Pader. He then learned that his brother had escaped a year earlier, only to commit suicide soon after doing so.The son of a school teacher, Anywar and two other survivors founded the Friends of Orphans School in 1999.

Ricky Richard Anywar:These are children of people who were killed during the war. These are very bright children. What they lack is the resources to educate them.

Fred de Sam Lazaro: Two decades on, about 300 young adults are enrolled, by now the children of the former child soldiers. They have been shunned and stigmatized socially, Anywar says, so the first task is to provide them with a safe space to just relax, play soccer, or play an instrument.

Ricky Richard Anywar: We use our stories to tell these children what happened to us. And with that, they get connected and open to us and begin working on the journey of their life.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Then it’s on to learning skills that are, at least in theory, in demand in the region, sewing and tailoring, masonry and building.Ricky Anywar guided me through the area’s towns. We visited a welding shop.

Man (through translator):The electricity is always on and off.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Power cuts are frequent, including on this day. It seven workers are paid by the piece, so no work means no pay.Next up, a music recording studio, Big Sound Productions, was started in 2011 by a former student at Ricky Anywar school, 30-year-old Charles Anywar, who’s not related.How is business now?

Charles Anywar:Business now, it is OK, but, then, I don’t have enough machines. I have the knowledge for the work, but I don’t have good machines.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Nearby 1,000 children attend this primary school in abysmal conditions, far worse than elsewhere in Uganda. Anywar’s group provides basic supplies for about 100 of them.

Ricky Richard Anywar:Most of these children, either they have worn-out uniforms, or they don’t have footwear.We select the children, those who are extremely needy.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Just how needy? I asked teacher Andrew Komakach.How many of these children have breakfast?

Andrew Komakach:None. None of — none of children.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:How about lunch?

Andrew Komakach:No, there’s no lunch for children.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:You think they are learning much?

Andrew Komakach:I don’t think so, because, when you are hungry, you cannot even study well.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:One of the paradoxes about trying to bolster education in this area is that the best and brightest are more than likely to leave cities like Kampala.The Friends of Orphans organization says, over the years, that it has about 100 youth who have gone on to earn college degrees. Of those, only one has stayed in the area.His name is Ronald Okello. He was abducted by the LRA at age 11 in 2001. Four years later, he lost his right arm in a gun battle, was captured by the Ugandan military and taken to a hospital, before being released.Ricky Anywar found him by chance wandering on the street as he drove by.

Ricky Richard Anywar:I had to stop. And I reversed back and asked him who he is. And he say, it is Ronald.

Ronald Okello:So, he took to Kampala, a very good school in Kampala.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:And then did you also go to college?

Ronald Okello:Yes.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:He scrapes by, he says, buying used shoes and household items in Kampala and reselling them in local markets like this one.Even for a degree holder, the prospects here are bleak.

Ricky Richard Anywar:Most of the international donors do not want to fund projects in this area, because they feel the war is now over.The international media’s attention always goes to where there are fresh wars around the world.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Some aid has slowly trickled in, like roads and power. It’s hardly enough. And there’s even less for social or reconciliation programs.Back in Lamunu, where Ricky Anywar’s group has provided some assistance before, the community turned out to plead with him for more help, a well for water, farm animals, proper clothing for the traditional dance group.For the “PBS NewsHour,” this is Fred de Sam Lazaro, reporting from Pader in Northern Uganda.

Amna Nawaz:And Fred’s reporting is in partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

A NEW GENERATION

A community in Lamunu, Uganda, is struggling to return to normal after decades of violent conflict that displaced nearly 2 million people. The Lord’s Resistance Army, led by Joseph Kony, abducted 35,000 children and deployed them as soldiers in an attempt to overthrow the government. Now, the children of those child soldiers are growing up in a community deeply scared but working to make a better future. Fred de Sam Lazaro explores how former child soldiers try to heal from the scars of war and achieve a better life.

Scars

Among other horrific atrocities, the LRA massacred 28 civilians in 2002 and cooked them in a pot leaving survivors deeply traumatized.

Reliving the Past to Heal

-Ricky Anywar, former child soldier

The Friends of Orphans

Ricky Anywar’s school for child soldiers and their children provides a safe space for the children who are shunned and stigmatized socially. The first task, Anywar says, is to provide them with a safe space to just relax, play soccer, or play an instrument. They also learn trade skills such as carpentry and masonry that are intended to give them a head start on finding a job – a bleak prospect in this economically depressed region.