William Brangham:This year marks the 25th anniversary of democratic rule in South Africa and the end of the brutal apartheid era. But many challenges remain, among them, providing equal education to all South Africans.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports on two unusual efforts to improve black education.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:It’s not a yoga studio, but a university, the Maharishi Institute, with a business model and curriculum as unlikely as its founder.

Taddy Blecher:This is what we do in the Maharishi Institute.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:Fifty-one-year-old Taddy Blecher trained as a statistical analyst in the insurance business. But after South Africa transition from apartheid, or racial segregation, he says he felt compelled to address its abysmal legacy in black education.Today, in Africa’s most advanced economy, just 37 percent of youth have the equivalent of a high school diploma.

Taddy Blecher:The realities in South Africa, even 25 years into freedom or democracy, now are pretty stark. There’s between 52 and 54 percent youth unemployment. So these youth get extremely disillusioned, often violent and angry.

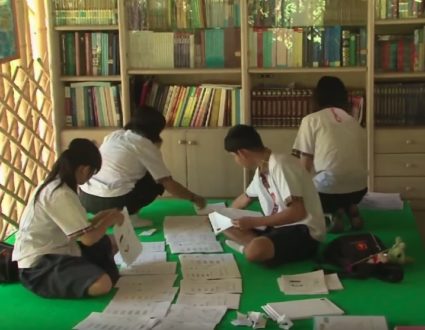

Fred De Sam Lazaro:Maharishi recruits begin with intense five-week orientation that stresses self-discovery and harmony. A follower of the Indian guru who preached meditation, Blecher says its improves concentration, motivation and reduces the high stress that dominates most students’ lives.

Taddy Blecher:In our intake this year and last year, not a single one of these students who’ve got grade 12 is actually at grade 12 level, not one. We don’t care how low a person is. We believe that person, because of their drive, could climb Everest.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:For students the early steps of that climb can seem, well, foreign.

Nontokozo Ndlovu:I mean, I’m black and I’m Catholic. And I’m like, what is this meditation?

Fred De Sam Lazaro:Nontokozo Ndlovu is a senior marketing major from Soweto, the impoverished black township that bears many scars from the anti-apartheid movement. This monument is to the 500 people killed in a 1976 protest against conditions in the schools.

Nontokozo Ndlovu:What basically happened was that thousands and thousands of students from different schools came out to fight this oppression.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:Today, the hurdles for black college aspirants are academic and financial. Ndlovu, raised in a lower middle-class family, says she could never afford to go anywhere but Maharishi, which costs about $170 a year, a fraction of the average university tuition in South Africa.

Nontokozo Ndlovu:I’m able to pay this amount because I work within the institute, and I’m able to get to school every day.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:Tuition is subsidized, thanks largely to partnerships with major corporations that receive tax breaks to aid so-called black empowerment programs, as well as on-campus businesses that also employ students.Between classes here in Johannesburg, students work in call centers on campus, taking orders for large restaurant chains. Then, at 4:00 p.m., seniors go online for some classes taught at the U.S.-accredited Maharishi University in Iowa, where the day is just beginning.More than 18,000 have graduated, Blecher says, with impressive results.

Taddy Blecher:We have an 80 percent graduation rate and 95 percent job placement rate.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:He says a key to their success is discovering their passions, then turning them into a vocation, something black South Africans were historically never allowed to do.The racially defined apartheid system may have ended 25 years ago, but educators will tell you that some of the stereotypes that it engendered are still very much alive. Among the most pervasive is that blacks are, by nature, not entrepreneurial.Patmanathan Pillai says it’s a stereotype that is deeply ingrained among non-white South Africans themselves.

Patmanathan Pillai:We need to recognize that oppression and internalized oppression is a part of who we are as a people.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:Fifty-six-year-old Pillai, whose ancestors came from India, runs a social business called LifeCo. It invests in sustainable businesses like wind farms and uses the profits for programs to train entrepreneurs, assisting people like Nonhlanhla Joye to develop their ideas into sustainable businesses.

Nonhlanhla Joye:We have cauliflower here. We have got thyme here.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:Joye’s business started out of necessity. As she recovered from cancer treatment and couldn’t work, she invented a low-cost way to grow organic vegetables.

Nonhlanhla Joye:When I started this, I was hungry. I had no food, I had no job, I had nothing. The only way I could feed myself was to grow vegetables in my garden.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:The idea, an urban garden that needs very little space, spread to her neighborhood.

Nonhlanhla Joye:It means these three bags can be able to feed plus-minus 10 to 12 people.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:Joye now has a network of more than 50 farming co-ops and schools.

Patmanathan Pillai:The kinds of entrepreneurs we work with are deeply aware of what inequality can do in this country. Despite these difficulties, what can you do to build your life, your community, your enterprise and so on?

Fred De Sam Lazaro:The key message from both Pillai and Blecher is to pass their knowledge and skills forward.

Taddy Blecher:So our idea is around connectedness, that everybody needs to help somebody else.

Fred De Sam Lazaro:That, he says, is key to improving the education and socioeconomic status of black South Africans, bringing some harmony to what remains one of the world’s most unequal and violent societies.For the “PBS NewsHour,” I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro in Johannesburg, South Africa.

25 years post-apartheid

It’s been 25 years since the end of apartheid in South Africa, but parts of the brutal era’s legacy still linger. Ensuring that all South Africans receive an equal education, for example, remains an elusive challenge. Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports on two unusual efforts to improve education and economic opportunity for black students in South Africa.

“The realities in South Africa, even 25 years into freedom or democracy, now are pretty stark. There’s between 52 and 54% youth unemployment.”

Maharishi recruits begin with intense five-week orientation that stresses self-discovery and harmony.

A follower of the Indian guru who preached meditation, Blecher says its improves concentration, motivation and reduces the high stress that dominates most students’ lives.