Judy Woodruff:The concept of orphanages has long been considered outdated in developed countries, and yet these institutions still house hundreds of thousands of children in the developing world.And, surprisingly, most of these children are actually not orphans.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports from Cambodia as part of his series Agents for Change.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Six year old Makara Rith spent three months in an orphanage in Battambang, Cambodia. But, on this day, his mother’s fingerprint made it official: He was going home.There, a counselor waited in welcome with toys for Makara and his siblings.

Makara Rith:I’m happy that I can see my mom and my sister and my brother.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Makara was one of thousands of Cambodian children who live in facilities commonly called orphanages here. Like him, the vast majority are not orphans. Neither parents nor the facilities are looking to offer the children for adoption.Parents, many in dire poverty, are easily convinced to place their children in these so-called residential care facilities, says Jedtha Pon, co-founder of a nonprofit called the Cambodian Children’s Trust.

Jedtha Pon (through translator):Most of them think that, in an orphanage, the child will have a better life with access to food, education and medical care.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Now Makara and his mother, Minear Norn, are part of an effort by several aid agencies working with Cambodia’s government to return children to their families.

Minear Norn (through translator):I feel like I have my child closer to me. Now I feel happy.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Happy that she now has all three children together. But this was a day of mixed emotions, guilt for sending her son away, worry about the future. She’s single and has no formal education.

Minear Norn (through translator):My life has been very difficult. We just survive day to day.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Under the new campaign, she will have help. For at least two years, Cambodia Children’s Trust provides a safety net for the families it serves.

Jedtha Pon (through translator):If they have domestic violence, they have mental health issues, or any children who are not going to school, we will work with the social worker. We also provide support in terms of food.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:The challenges for this family and for the broader campaign are daunting. It begins with the image Cambodia cannot seem to shake, of the Khmer Rouge genocide, its two million victims, displayed in museums, immortalized by Hollywood.

Sebastien Marot:Cambodia 2019 has nothing to do with Cambodia 1979.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Sebastien Marot founded a vocational training charity 25 years ago that’s helped thousands of marginalized children and their parents.

Sebastien Marot:The movie “Killing Fields” and all the movies that came out about Cambodia is about this. So, when people think Cambodia, they think that all the children are being victims of destruction, and everyone is an orphan, which is far from the truth.

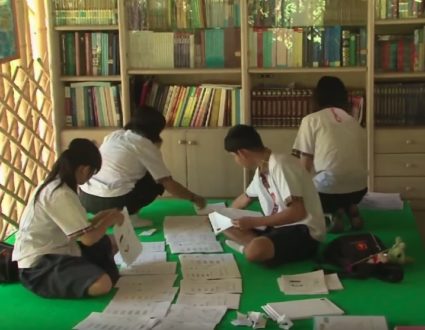

Fred de Sam Lazaro:With the civil strife over, he says there are far fewer orphans now. Many children still live in poverty, but their number has also dropped amid robust economic growth, notably in tourism to Cambodia’s world famous temples.There may be fewer orphans, but orphanages have also become a growth industry. There were about 150 in 2005. Today, there are more than 400, housing more than 16,000 children. Often, they are put on display, dancing for tourists who are then coaxed to leave a donation.

Dara Roeum (through translator):We learned to dance. We performed for foreign visitors. It’s not fun. It’s so exhausting.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Fourteen-year-old Dara and his sister, Dary, who’s 9, were recently reunited with their mother after six years in an orphanage, where they recalled lives of physical abuse and insufficient food.

Dara Roeum (through translator):It wasn’t fun.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:There’s profit, Marot says, in pity.

Sebastien Marot:It’s an easy sell. A child in a terrible situation, fly on the eye, give me $5 a month. If it were that easy, it would be fantastic. But it’s not.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Then there’s voluntourism, a thriving industry in which college or gap year students pay agencies to place them in orphanages.Each year, tens of thousands of young Australians, Europeans and North Americans come to Cambodia to volunteer. They will spend a few days, sometimes weeks in orphanages, mostly teaching English to the children.Child development experts say not only does this not help the children; it actually harms them.

Sebastien Marot:It comes from a very good feeling that, I’m helping, but, realistically, would you like to have your teacher change every week?

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Children thrive on nurturing long-term relationships with adults, the kind usually found only in a family.

Sebastien Marot:The development of a child, especially a young child, is hindered dramatically by being in an orphanage, by the lack of personal attention, by not being in a family.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:But to Ted Olbrich, it depends on the family and the orphanage.Olbrich is an American evangelical pastor who, with his wife, Sou, founded Foursquare and Children of Promise, the largest of several faith-based operators of residential care facilities, or, as he calls them, church homes.Some older religion-based groups have joined the campaign to de-institutionalize children. But others, like Foursquare, have resisted. The Olbrichs say they opened their first church home in the early ’90s because there was a pressing need.

Ted Olbrich:We didn’t come here intending to take care of orphans. We came here to build a church, and we wound up having these kids dumped on our doorstep.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:And that need has only grown, he says, to 106 homes, driven by family dysfunction that’s widespread and social mores.

Ted Olbrich:Our biggest source of children is children that had mothers who died in childbirth. Now those children are considered cursed.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Widows are also marginalized in Cambodia, he adds, and they are brought in to staff their facilities. Each has about 25 children.

Ted Olbrich:These widows, they live with the kids, and they’re there with the kids their entire life that they’re growing up in the orphan homes.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Many then profess their Christianity, not a requirement, he says, but a good outcome.

Ted Olbrich:I’m a proselytizer. We absolutely…

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Unapologetically?

Ted Olbrich:Unapologetic proselytizer.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Sebastien Marot says Olbrich is exaggerating Cambodia’s social ills and says his mission would be intolerable if the tables were turned.

Sebastien Marot:I’m sure they would be very upset if a Muslim organization opened centers in the U.S. or in France, started taking children from communities, put them there to turn them into nice little Muslims. And this is what they’re doing here. It’s a Buddhist country.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:He says orphanages are an outdated concept, closed long ago in France and the U.S., in favor of placing children in foster families and adoption.That’s the goal in Cambodia, but it’s not easy, given the poverty that keeps life fragile for many families and limited resources for family reintegration, which, ironically, is the cheaper option.

Jedtha Pon (through translator):It’s about 10 to 15 times cheaper to support a child living with their family, rather than to bring them into an institution.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:The Olbrichs say their institutions are family, and they have no plans to scale them back.The Cambodian government’s goal is to reduce the number of children in orphanages by a third by next year.For the “PBS NewsHour,” this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Battambang, Cambodia.

Judy Woodruff:Fred’s important reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

A growth industry

Orphanages are outdated in many parts of the world, but in some developing nations they’ve been a growth industry, even though most children in them are not orphans.

“The development of a child, especially a young child, is hindered dramatically by being in an orphanage, by the lack of personal attention, by not being in a family.”