Fred de Sam Lazaro

This Buddhist monastery campus in central Thailand was built as a drug rehabilitation center. Today it’s a sprawling dilapidated village fenced in by the military, inhabited by perhaps the last refugees from the war in Indochina. For about two decades, thousands of Hmong, an ethnic minority from Laos have looked from camp to camp in a stateless limbo. Early this year, the US said it would grant refugee status to about 15,000 residents of this camp, anywhere from 1500 to 5000, are expected to move to St. Paul, Minnesota, which has the largest Hmong community of any American city. Anticipating a new influx, St. Paul Mayor Randy Kelly brought a delegation to the camp. He said he wanted to assess how many people might move to Minnesota and what their needs would be in areas like education, housing, and health care. A huge crowd greeted the visitors.

Randy Kelly

And I would like to begin by thanking you for the support that many of you gave to our country in the war in Vietnam.

Fred de Sam Lazaro

It was their close anti-communist alliance with the CIA that forced the Hmong, people like Chao Lor to flee Laos when communist forces took over.

Chao Lor

I had to carry my sons on my back until it was calloused. We had to run away through the jungle from people trying to kill us. I didn’t think we’d make it.

Fred de Sam Lazaro

Several thousand Hmong refugees were given asylum in the US during the late 1970s and early 80s. It was a painful transition for an agrarian, isolated community from the tropical Laosian Hills, says Mee Moua, the first Hmong elected to Minnesota’s Legislature.

Mee Moua

Imagine landing at the Minneapolis St. Paul airport in the middle of a blizzard, which has happened to some of my relatives to say, and this is America. You know, it’s it’s physically shocking. It’s visually shocking and it is emotionally draining to try to process all of that.

Fred de Sam Lazaro

Even as they brought old traditions like Hmong New Year festivities to new venues like the Minneapolis Metrodome, the Hmong more than most immigrants struggled with language and cultural barriers. Few people in host communities understood either their language or culture. Two decades later, life remains a struggle for many, but St. Paul’s Hmong community has made significant strides. Almost half of Hmong families own their own homes, and there are 400 Hmong owned businesses in the city. Senator Moua, a lawyer by training is one of many success stories.

Randy Kelly

We have state senators, Mee Moua, we have a state representative, Si Kao. We have a school board member Gjoua Kong. We have a number of Hmong who have been and are very successful in our political life in our community.

Fred de Sam Lazaro

Attorney Eileen Her who came to the US at age six in the first wave, thinks the role the Hmong community is playing in the newest resettlement is critical

Eileen Her

The first time around like 30 years ago, the Hmong community was not a part of the discussion at all. And now we are and we’re part of the solution. And that I think, to me is very healing and I think that’s what the community here needs to hear

Fred de Sam Lazaro

Wherever Her and other Hmong Americans went. They found hugs, tears and pleas for help.

Eileen Her

Her husband is old they don’t think they can make it in the US.

Fred de Sam Lazaro

Some camp residents pleaded for help to remain in Thailand, a place that’s become familiar after decades. But the Thai government has ruled out permanent residency for people it considers illegal migrants. Others especially older people remain faithful to the original cause of fighting the Laosian government and want US help

one of Chao Lor’s four sons remains a guerilla in the jungle. Another two went to America in the 1980s. At that time Chao Lor and her fourth son, Chai Chang stayed behind to help her husband who was addicted to opium. By the time he died, the window of opportunity to go to the US had closed. Now she says this family’s painful separation may finally end.

Chao Lor

I’m very hopeless. I’m sad because my family is broken up. Ones in Laos, ones in America, ones in Thailand. We have no future here.

Fred de Sam Lazaro

Her son and daughter in law are concerned about their own ability to adapt to life in America.

Chai Chang

I’m worried that I won’t be able to get a job because I don’t speak English.

Fred de Sam Lazaro

But they’re excited that the better future their seven children will have. For the past decade, they’ve shared a 400 square foot mud floor shack. They must walk past open sewers for basic amenities like water and sanitation. Schools in the camp are crowded, most classes are taught in Thai.

Schoolchildren

Hi, Randy!

Randy Kelly

Study hard, learn english, and when you come to America, you’ll be ready to learn and become very successful.

Fred de Sam Lazaro

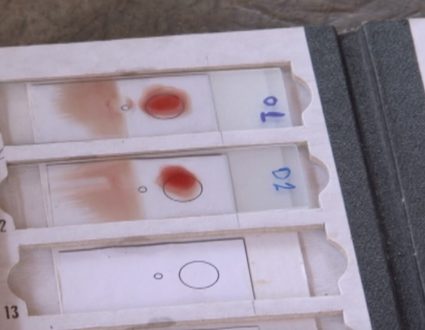

Despite all the privation the new generation has more going for them then earlier waves of Hmong refugees, the chain kids have access to the internet and television. On the health front, there are a few resources to create everyday problems like diabetes, and none for specialized needs counseling for post traumatic stress syndrome, which many elders suffer. Still Dr. Patricia Walker, a public health expert said she found no major health threats.

Dr. Patricia Walker

In talking with medical staff here preliminary first impressions are that this is a reasonably healthy camp, it’s certainly not like an acute refugee camp setting. The water supply is reasonably good, sanitation is reasonably good, people get some money from home in the United States and therefore can buy eggs and chicken and vegetables and not seeing a lot of vitamin deficiencies.

Fred de Sam Lazaro

For this family, those relatives in the United States include Chao Lor’s sister, Mee Lor, who lives in St. Paul. They’ve seen each other only once in 17 years. We showed Mee Lor pictures from our visit to the Thai camp.

Mee Lor’s Translator

She said that when she’s come here, her sister still looked young. Now, her husband die and she looked old and she will miss her.

Fred de Sam Lazaro

She lives with her son, wife and eight children in a St. Paul bungalow. In the extended family tradition where resources are pooled, they make a living doing factory work, running a cleaning business and a restaurant. They are anxious to reunite the family even though it means 10 more people will squeeze into this house for a while, and even with some public assistance to start, Marie Chang says it will be a financial struggle given the tough local job market for the newcomers.

Unknown Speaker

I think before it’s not hard, but now is like business slow, but I think if they don’t care about the wage, so they will, they will be able to find a job.

Fred de Sam Lazaro

The slow economy is one reason not everyone in Minnesota is thrilled at the prospect of more Hmong settlers. The mayor’s office, for example, has a stack of mail and messages critical of his trip.

Mayor’s office employee

Why is the mayor bringing Hmong, the Hmong immigrants to our city. There’s like one that just said my son’s out of work is very much opposed to Hmong immigrants resettling here.

Fred de Sam Lazaro

For his part, the mayor insists he isn’t inviting new Hmong refugees, instead, he said just wants to get a better handle on the needs of those who’d come to Minnesota anyway. But at the end of a moving day at the camp Kelly said if his trip made St. Paul seem more hospitable than other places, the Hmong deserve that.

Randy Kelly

Quite honestly, I think that this group of people have been neglected, have been forgotten. And I believe that as an American, we need to show that those people who come forward and assist us and become our allies should be treated properly. And I’m not sure that they have been. So if I can, from a standpoint of representing the United States, extend a hand of welcome when I know they’re coming to America, then I’m honored to do that.

Fred de Sam Lazaro

Camp residents must now undergo a rigorous battery of clearances for security and health risks and interviews to determine that they are political, not economic refugees. The first arrivals are expected this summer.

The second wave

Two decades later, life remains a struggle for many, but St. Paul’s Hmong community has made significant strides. Almost half of Hmong families own their own homes, and there are 400 Hmong owned businesses in the city.