Judy Woodruff:We continue our look now at how COVID-19 is reverberating across the globe.Bangladesh, in South Asia, is about the size of Iowa, but has 50 times as many people. That makes containing coronavirus a huge challenge, as does the recent influx of a million refugees from neighboring Myanmar.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports on efforts by one Bangladeshi non-governmental group trying to tackle the problem.It’s part of his series Agents for Change.

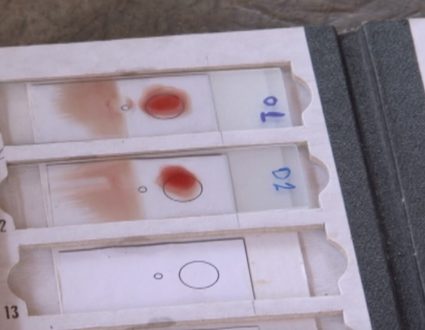

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Testing is only now ramping up in Bangladesh, so the 20,000-odd COVID cases and 300 deaths reported so far could rise significantly in the days ahead.That’s especially true in Dhaka, a bustling, chock-a-block capital city, home to more than 20 million people. Like the rest of the country, Dhaka has been in lockdown since late March, squeezing people into even less space. The infection control challenge is plain to see, how to practice distancing when there’s so little space or handwashing when most homes lack running water.

Asif Saleh:We are trying to plug holes in the public health care system to support the government.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:From my home in Minnesota, I reached Asif Saleh with the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee, or BRAC, the world’s largest non-government aid group.BRAC plans to set up 600 testing kiosks across the country and is working with the military to expand quarantine facilities. Most urgently, it’s also supplementing efforts by the government to get food to people.

Woman (through translator):They are distributing rice and dhal lentils, and I’m here to pick that up. I am hungry. I have not had anything for four days.

Man (through translator):I’m here because I’m trying to survive. I’m jobless. Everything is closed.

Question:How long will this food last you?

Woman (through translator):Hardly two to three days. They give us 10 pounds of rice, and there are seven to eight people in my family. This is the kind of pain we’re facing.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Tens of millions of already struggling Bangladeshis, like rickshaw pullers and laborers who rely on daily wages, have lost their means s of survival.

Asif Saleh:Beyond the public health crisis, there’s a massive economic and humanitarian crisis that is emerging because of this lockdown. People who don’t — who are not monthly wage workers, they don’t have any savings. So, they’re practically facing severe starvation.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Two hundred and fifty miles southeast of Dhaka lives another particularly vulnerable population, more than one million Rohingya refugees who’ve fled here from what the U.N. has called genocidal violence in neighboring Myanmar.The first confirmed COVID case inside the camp was reported yesterday. But there’s not much testing available, so no way to know how widely the virus has spread here.What has spread, in the camp and across the country, is misinformation and fear.

Asif Saleh:They’re thinking that, you know, I’m going to die, or I’m going to get taken away, or we’re not going to be able to get food. We need to move out of the lockdown situation and come up with a post-lockdown strategy

Fred de Sam Lazaro:For BRAC, that means awareness campaigns to spread accurate information involving local communities to create quarantine spaces, and train contact tracers for a possible outbreak.For the government, a key priority has been to get people back to work, especially garment workers like Parul Begum.

Parul Begum (through translator):We are here sitting in the middle of the road because we are hungry.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:In Bangladesh’s economy, there is perhaps no more essential employee than the garment worker. Four million of them, earning about $100 a month, work in thousands of factories and produced 80 percent of this country’s total exports earnings.It all ground to an abrupt halt when the government declared a total lockdown. Garment workers were sent home, many without being paid, and throughout the shutdown, there have been protests in the streets.

Question:Have you been paid for March?

Woman (through translator):How can we live? Our rent is due and the landlord is kicking us out. we have kids. We have school fees. Our house is running out of food.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:They have been impacted not just by the COVID lockdown here, but by European and American clothing retailers facing a meltdown in demand, says workers rights advocate Kalpona Akter.

Kalpona Akter:Many brands and retailers started canceling their orders by saying that all the shops are closed and consumers are not buying at this moment, so they cannot take the product, which already made, and those are already in the production.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Several brands reversed course, she says, after a campaign her group conducted with the Washington, D.C.-based Workers Rights Consortium.It launched a site tracking which brands are and are not honoring their earlier purchase commitments. Still, Bangladesh factory owners spokeswoman Rubana Huq says they’re down more than $3 billion in canceled orders and stuck with nearly $2 billion worth of fabric.

Rubana Huq:For all the raw materials, the entire liability is on our shoulder. We are very, very sympathetic to all the retailers who are suffering, because, without them, there would be no business.It’s just that we want them to also kindly realize that there’s a different reality out here. The reality is, there are lots of people who are going to go hungry.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:We reached out to American companies the tracking site claims went back on their Bangladesh commitments, including Gap, J.C. Penney, and Kohl’s, but have received no response.Amid all the uncertainty and a lockdown, garment factories were allowed to reopen in late April. There are still plenty of pending orders, and owners say they have added safeguards to sanitize the workspace and put more distance between workers.Workers advocates say it still leaves a lot people in still-crowded spaces in a country ill-equipped to handle COVID outbreaks, but one that’s counting on this work force to anchor its economic recovery.The fate of Bangladesh’s garment industry post-COVID will depend heavily on consumer behavior in wealthy countries. Will they come back to malls, go online, and buy like they used to? Or will appetites and fashion have shifted?Most critically, when will all of this start to become clear?For the “PBS NewsHour,” along with Salman Saeed in Dhaka, I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro outside the shuttered Mall of America in Minnesota.

Judy Woodruff:Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

The perfect storm

As COVID-19 spreads in Bangladesh, cancelled contracts and factory closures have left millions of garment workers furloughed and hungry. Meanwhile, the first cases of COVID-19 have reached the country’s Rohingya refugee camps, where close to a million refugees are vulnerable.

Bangladesh

“How can we live? Our rent is due and the landlord is kicking us out. we have kids. We have school fees. Our house is running out of food.”