FRED DE SAM LAZARO:For Haitians, the HIV epidemic has been long, painful, and at times humiliating. At first, scientists thought the AIDS virus was brought to the U.S. from here. Haitians were put on a watch list of four “h”s, along with heroin users, hemophiliacs, and homosexuals. First Lady Mildred Aristide lived in New York at the time.

MILDRED ARISTIDE:I was a college student in ’83 or so, and we were going to do a blood drive. And that was one of the questions asked by the Red Cross, that was collecting blood: Whether I had recently visited Haiti or was of Haitian origin. And so that has made it a special issue, because there had been an attempt to label Haitians as being a cause of the disease.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Although unfairly stigmatized, Haiti does have a serious AIDS problem, one that experts tie directly to its extreme poverty. Two-thirds of Haitian adults are unemployed. Some 300,000 people– about 5 percent of the population– is infected with HIV, the AIDS virus. It’s the highest incidence in the western hemisphere. Still, Dr. Jean William Pape, who returned to his native Haiti from New York 20 years ago, says the number is well below what might be expected.

DR. JEAN WILLIAM PAPE:We have all the factors that would predispose this country to have rates as high as 40 percent, 50 percent — especially the disease started here early; it spread very fast in the heterosexual population. We have the highest rate of sexually transmitted diseases. We have also… we’re the poorest country with a very high rate of commercial sex workers who are HIV-infected. If you put all this together, this is the best recipe for an explosion of the HIV epidemic. Yet this has not occurred.

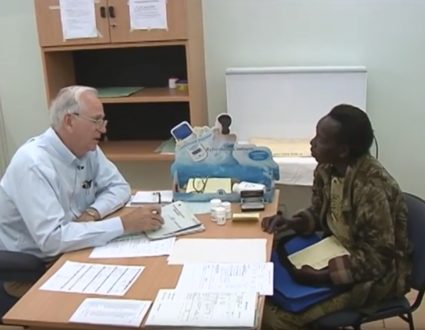

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:One reason it hasn’t occurred is the work done in Dr. Pape’s Gheskio Center in the capital, Port au Prince, and a rural project called Partners in Health. They’ve developed low-cost approaches to prevention, testing, and care– for example, controlling the incidence of sexually transmitted diseases, which increase the risk of HIV Infection; and for those already infected, treating complications like severe diarrhea. Their success recently earned Haiti an award of up to $67 million over the next five years from the U.N.’s global fund for AIDS, Malaria, and tuberculosis. It will greatly expand the public health effort, and also make available medicines including antiretroviral drugs. Haiti will be the first developing country in which these so-called cocktail drugs will be somewhat widely distributed. These medicines have allowed AIDS patients in rich countries to lead almost normal lives. But they’ve long been considered too expensive and not feasible in poor countries like Haiti. Dr. Paul Farmer has long campaigned to change that thinking.

DR. PAUL FARMER:One of the biggest set of myths we’re dealing about are about therapy for HIV “HIV.. it can’t be done in a placed like this; you know, people don’t have other rights; they don’t have a concept of time; they don’t have wristwatches; the medications have to be refrigerated; it’s not cost effective.” You know, it’s not anything you would ever initiate in a really poor country.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:For 20 years, Dr. Farmer has divided his time between Harvard Medical School and the Zanmi Lasante, or Partners in Health Project, he founded in Haiti’s remote central plateau. Since the late ’90s, when prices for some AIDS drugs to decline, partners in health has provided antiviral medications to as many patients as it can. On a limited budget, the drugs are funded mostly by private donations, and like all services here, free to patients, most of whom could not afford them anyway. 41-year-old San Coeur Francois says he feels like a modern-day Lazarus. He was brought in three years ago so close to death his family had purchased a coffin. With drug therapy, he quickly recovered and has had almost no health problems. Life is still a struggle. Francois cannot find employment. His wife and two daughters moved temporarily to Port au Prince to find work. But he’s thankful for the chance to see his children grow up.

SAN COUER FRANCOIS ( Translated ):After god, I am most thankful to dr. Paul. My weight was 95 pounds. I’m up to 142 now. The medications have done so much for me. In Haiti, certainly those in port au prince knew these medicines existed, but the price was so exaggerated. But here, patients don’t pay anything for the medications.

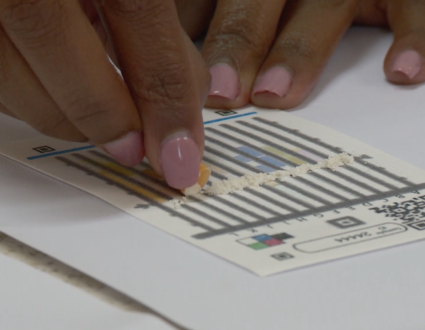

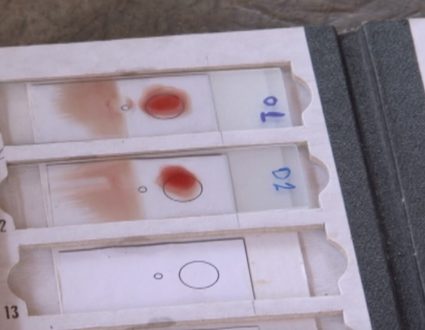

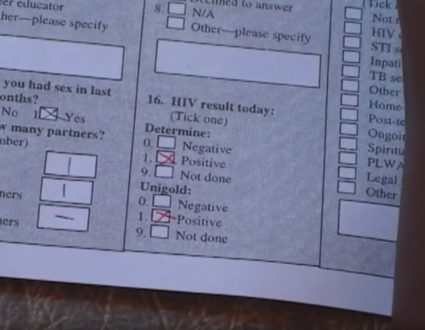

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:One unanticipated benefit of bringing antiretroviral therapy to rural Haiti is that many more people are coming into clinics to be tested for the AIDS virus. For the first time, doctors say, people have been able to witness AIDS patients, people dying of AIDS, get better.

DOCTOR:Suddenly you have treatment, and a lot more people want to be screened; you’re going to get a lot more people who are negative, who are sero- negative– that is, they don’t have HIV. And that’s where you can start making interventions to keep them from getting HIV.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:There are other benefits as well, even for those who don’t receive the limited supply of drugs. They can be treated for opportunistic infections, which kill thousands of AIDS patients in poor countries. Tuberculosis is rampant in Haiti, for example, yet easily treated for just a few cents per patient. 19-year-old Ketya, who is HIV-positive, lost her mother and two siblings to tuberculosis. She now lives with her father. Both have been treated for T.B. To ensure medicines get to patients like Ketya, who are too poor and too far away from the clinic, volunteers like Estany Deomille are recruited to visit patients every day. Some days a doctor comes along, like David Walton, a recent Harvard Medical School graduate. Ketya may need aids drugs later, he says, but for the moment, she needs money. The small plot they farm cannot cover rent on their tiny home, or the fees to help Ketya finish school. Partners in Health will provide the money, an investment in AIDS prevention.

DR. DAVID WALTON:If she didn’t had money to pay the house, and she didn’t go back to school, she’d have to do something to put food on the table and to help her father, and that may entail maybe going to Port au Prince or choosing a partner who has… who can give her some kind of financial assistance.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Prostitution, in essence?

DR. DAVID WALTON:In a way, you can view it as such.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Paul Farmer called it survival sex yesterday.

DR. DAVID WALTON:That’s perfect– survival sex. She’d have to have sex with this person to survive, and this person would likely have other partners, and so she’d be exposed again. And then if he wasn’t sick, she’d be exposing him. So, I mean, this is the way in which we epidemiologically can kind of step in and stop the progression and the spread of disease.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:But Haiti has numerous other hurdles that hinder public health. Poor roads means it takes too long to get medical care.

SPOKESMAN:Bonjour, Isaac.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Isaac was brought in too late, suffering from typhoid, a common waterborne killer in a country where 80 percent lack safe drinking water.

DOCTOR:I don’t think he’s going to make it.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Reporter: Despite all the hurdles, Dr. Pape says Haiti has significantly curbed the incidence of HIV and related infectious diseases. And those efforts will get a major boost with the global fund grant. (Baby cries) But ironically, most of the money will go toward uncovering yet more need. 25 new testing and counseling centers will be opened across the country. Haiti’s first lady, who oversees the government’s AIDS effort, says many more people will get HIV tests, and this could greatly help in prevention.

MILDRED ARISTIDE:I think the most important tool that the global fund project brings is this capacity, because then Haitians and women specifically– because the women, in my estimation, have been the most vocal in wanting to know their status– could be active agents of prevention, information, education, passing that onto their children. But they need to know, and right now, we don’t have the capacity for folks to be able to be tested.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Dr. Pape’s goal is to reduce Haiti’s HIV prevalence by half. That won’t eliminate the epidemic, but he’s optimistic it will bring it under control.

DR. JEAN WILLIAM PAPE:We used to say that only the optimist people have stayed in Haiti. So you are talking to an optimist person.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO:Reporter: Experts share that optimism, and say it could translate into hope for many developing countries ravaged by AIDS.

Partners in Health and the Gheskio Center

In 2003, President Bush signed a bill approving a five-year plan and $15 billion to fight AIDS worldwide. Fred de Sam Lazaro reported on the epidemic’s toll in Haiti, one of the countries that will benefit from the new plan. The problem could have been a lot worse if not for the work of two innovative doctors at the Gheskio Center in the capital Port Au Prince and a rural project run by the Partners in Health.