Judy Woodruff:President Biden has proposed using some of the $2 trillion in his infrastructure plan to repair the harm done to many minority communities when highways were originally built through them.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro has the story of one such example from Minnesota’s capital, St. Paul.It’s part of our Race Matters series.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:For most drivers, this is just I-94, the freeway in and out of downtown St. Paul. But for 73-year-old Bill Finney, the city’s police chief, this is more hallowed ground

Bill Finney:We are now parked from the spot of where my house was.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Wow.The Finney home in this spot was taken away by the freeway six decades ago, his one of 700 families displaced from St. Paul’s once-thriving and tightly knit Black neighborhood.Going down memory lane for you.

Bill Finney:Oh my God, yes. Yes.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Those families are memorialized at a plaza commemorating the Rondo community’s evisceration dismantling by I-94, shaded yellow on the map.

Bill Finney:And so that disrupted a whole lot of people I see present in these pictures. And, in some cases, some of the folks even moved out of state.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:The community was never quite the same?

Bill Finney:Never, no.

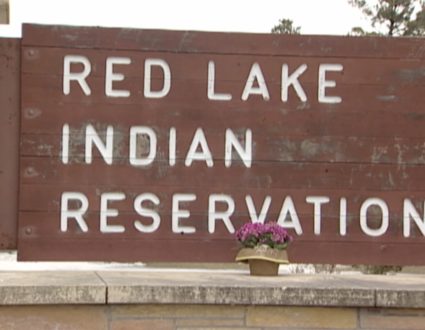

Fred de Sam Lazaro:It was one of thousands of communities where land was taken by eminent domain to build the Interstate Highway System, approved in 1956 and by far the largest infrastructure project in U.S. history.And Finney, who in retirement serves as a county undersheriff, says Rondo fit a pattern.

Bill Finney:I ride motorcycles, and I ride from coast to coast, north to south. I notice that where the freeway is very, very straight for as far as you can see, you know one of two things. They’re either going through a rural area or they’re going through a poor area.Then, all of a sudden, the freeway makes rights and left turns and sometimes switchbacks and stuff like that, and you understand that they’re going around people that have money or businesses.And I don’t think that’s right. But people that didn’t historically have a large voice had little to say.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:The path of least political resistance.

Bill Finney:Absolutely.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:He and others say the displaced Rondo families were paid less than their homes were worth, and they struggled to find new housing in a city where many areas didn’t allow Blacks to settle.They were displaced not just from Rondo, but from the middle class, says civil rights attorney Artika Tyner, a fifth-generation daughter of Rondo.

Artika Tyner:They lost that sense of building intergenerational wealth, of being able to pass down homes and businesses too.Sometimes, we just talk about the homes, but, at its peak, Rondo had over 300 businesses that were Black-owned. We still feel a ripple effect today. Not only does Minnesota have one of the lowest rates of homeownership of African Americans in the nation. We also have some of the greatest disparities in poverty rates between Blacks and whites.

Chris Coleman:Today, we acknowledge the sins of our past. Today, we ask for forgiveness from those who lived through those days when our community was at its worst, and for those who continue to rebuild the shattered pieces of Rondo.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:In 2015, the city of St. Paul held a ceremony to apologize to the Rondo community.

Artika Tyner:The apology is a starting point, and not a resting place. I can’t cash an apology at the bank.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:What many community leaders in Rondo say would really put this neighborhood back together again is an idea that would do so quite literally and in concrete.It’s called ReConnect Rondo, a land bridge that would be constructed over a five-block stretch of I-94.

Keith Baker:It’s simply creating an African American cultural enterprise district that’s connected to a land bridge, a structure. And on top of that structure, you can put elements that improve quality of life.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Executive director Keith Baker says the project envisions affordable housing, business incubators, gathering spaces and cultural amenities aimed at the Black community, all managed by a trust to insure that benefits stay in the community.

Keith Baker:We just want to use the same systems, processes, tools and resources that benefit business to be used to benefit community

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Such as?

Keith Baker:Well, let’s just think about the Target Field.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:This is the baseball field for the Minnesota Twins.

Keith Baker:Right. That sits over an infrastructure project, a highway, very familiar, has been done, but leveraged in the interest of business. The same thing can happen, in my mind, in the interest of community.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Just as states and cities subsidize the construction of Major League stadiums to stimulate economic development, he says, the ReConnect Rondo project will create jobs.The cost, in state, private, philanthropic and, critically, federal infrastructure dollars is projected to approach half a billion dollars.

Keith Baker:I’m an optimist by nature, but I’m a realist as well, OK? I know that this is not an easy proposition.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Among prominent St. Paul residents making a very personal case to Minnesota lawmakers for transportation dollars is the city’s first Black mayor, Melvin Carter.

Melvin Carter:My family was among those who had their lives and their livelihoods uprooted in the name of progress.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Also promising, pledges from the Biden administration to address inequality and racism.Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg discussed how infrastructure projects could figure into that push.He spoke to the news Web site The Grio.U.S. Secretary of Transportation, Pete Buttigeg: There is racism physically built into some of our highways. And that’s why the jobs plan has specifically committed to reconnect some of the communities that were divided.

Keith Baker:Nothing is ever guaranteed. But I think there is alignment that’s taking place right now. And we must seize that.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:ReConnect Rondo will not bring back what was lost 60 years ago. But Artika Tyner says it offers a chance to sew back a community like the one she was raised in and writes about in children’s books about elders children can look up to.

Artika Tyner:The highlight of living and growing up in Rondo were the small businesses, the inspiration, the role models, like looking at the McGhee law office to inspire me to become an attorney myself. It’s that old notion of you can’t be what you cannot see.That young child Joey, he’s excited about the time that he spends with Grandpa Johnson.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:For now, a $6 million request to conduct feasibility and environmental assessments of the ReConnect project is part of budget negotiations just a couple of miles from Rondo at the state capitol. They will know in mid-June.For the “PBS NewsHour,” this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in St. Paul.

Judy Woodruff:And Fred’s report is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

A community bulldozed for an interstate

The Rondo neighborhood in St. Paul was once a thriving, predominantly Black community—before it was destroyed when land was taken by eminent domain to build the interstate highway system, approved in 1956 and by far the largest infrastructure project in U.S. history.

Where Rondo used to be

“They lost that hope… that sense of building intergenerational wealth, of being able to pass down homes and businesses too… Not only does Minnesota have one of the lowest rates of home ownership of African Americans in the nation, we also have some of the greatest disparities and poverty rates between blacks and white.”