Amna Nawaz:Well, the effects of the pandemic on children vary dramatically depending on the country. With schools still shuttered in Uganda and other developing nations, many children have no choice but to work to survive.In Africa, more than a fifth of all children, or some 87 million kids, work.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports from Kampala.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:It looks like a scene set in the Middle Ages, a gaping, sprawling stone quarry just outside Uganda’s capital.It is also a gravel factory, all of it done by hand, large, small, and very small hands. Evelyn is 11 years old. She works every day balancing on a makeshift ladder to crack open the rock face. Her family will then pound the larger rocks into gravel with crude hammers.For some, the only available tool is a larger rock. Evelyn’s mother, Sylvia Naggujja, who has done this work for more than a decade, labors by her side, next to six brothers and sisters. For all this work, they earn less than $2 a day. That’s the whole family.

Sylvia Naggujja, mother (through translator):We go and break stones. Like, that plastic jerrican you see there. We fill it at 300 shillings for each jerrican.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:It’s exhausting, dangerous work, a scene repeated at dozens of sites in the area. Accidents and injuries are common, especially among young children.

Evelyn, Uganda (through translator):Life is not OK. When I break these stones, sometimes, they cut my fingers. Sometimes, the small pebbles fall into my eyes. Life is not good. Another time, a big stone hit me on the head right here.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:But what weighs on Evelyn most is her life before the pandemic. Aside from a few weeks between Uganda’s two COVID surges, schools have been shuttered across this nation of 44 million.

Evelyn (through translator):I miss school. I miss work at school. I work every day. I would like to be a doctor or a nurse. I wanted to go to school, go to university, possibly go abroad and help my mother.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:It is not uncommon to see young children doing hard work, fetching water or wood for the family cook stove.But, whether in quarries, mines, or farmland more and more children are being forced to work for their survival. 2020 was the first year in two decades that saw an increase in child labor around the world. And with the pandemic devastating economies, the United Nations says the problem is getting much worse.It issued a report that found 160 million children, some as young as 5, working in child labor, many doing tasks that directly threaten their health and safety.Angella Nabwowe, Initiative for Social and Economic Rights I saw a 9-year-old in a gold mine.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:As the mother of a 9-year-old herself, human rights advocate Angella Nabwowe says the encounter stopped her in her tracks.

Angella Nabwowe:I was practically looking at my daughter doing that work. I talked to this girl. She lives with her grandmother. They have nothing, nothing. A 9-year-old in a gold mine working, it is not right. It’s not.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:She says years of progress have been wiped out by the pandemic, as have the income and prospects of a large number of Uganda’s poorest people, who live hand-to-mouth in the mostly informal economy.

Angella Nabwowe:The urban areas, the official data is that 23 percent of that lost everything. They do not have any source of what? Income, because of COVID-19.

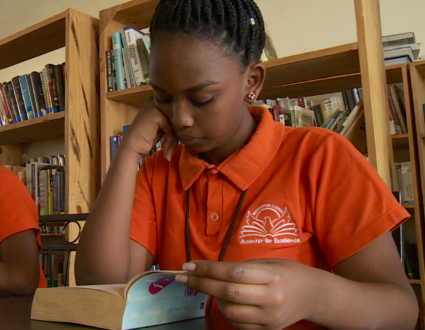

Fred de Sam Lazaro:It’s not just income, she says. For many children, the loss of school has deprived them of a reliable meal each day. As we saw in this school in 2017, meals are often provided across the developing world to boost both nutrition and attendance. That all stopped when the schools closed.

Angella Nabwowe:Food is a basic right. People don’t have what to eat. And what is the effect of that?

Tyler Dunman, Human Trafficking Institute:It’s been pretty catastrophic.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Tyler Dunman, a lawyer with a human rights group, is on loan to Uganda’s director of public prosecutions. Unlike children such as Evelyn, who work with their parents, many have been trafficked into labor, he says. It’s illegal, but enforcement is spotty, complicated further by the pandemic.

Tyler Dunman:Oftentimes, they’re finding themselves on the streets begging, or being forced to sell things, or, as they call it, hawking things here. Those situations have increased exponentially.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:So has trafficking into the sex trade, he says. Young women are particularly vulnerable. And there’s another risk. Social workers we talked to say they have seen a spike in teen pregnancies.

Esther, Uganda (through translator):I’m 15 years old.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:We visited Esther in this Kampala slum. She enjoyed school and got good grades, and, when school stopped, she took a job in a food stand to help out the family.Then she became pregnant, the result of boredom and rebellion, she now admits. When the baby arrives in February, school will be out of the question, impractical, she says, and unaffordable.

Esther (through translator):I was studying to become a doctor. I missed the company of my friends. We used to sit down there. We would talk. We would be reading books.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:What is your dream for your future?

Esther (through translator):My dream is, if I have a chance, I want to learn how to weave hair, do hair, and, in the process, be able to start my own business.

Rogers Mutaawe, Uganda Youth Development Link:How do they survive? Because their parents cannot meet their basic needs.

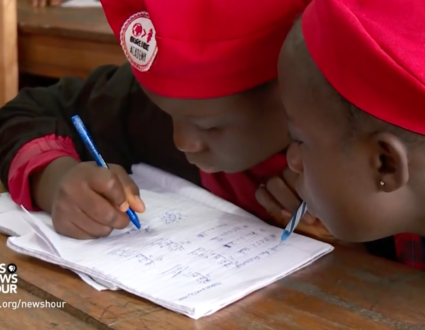

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Rogers Mutaawe runs the Uganda Youth Development Link, part of a team of charities that work with at-risk youth. Since March of 2020, the number of young people they’re helping train for safer jobs has nearly doubled.When we visited, they were learning baking, cupcakes on this day.

Rogers Mutaawe:And so we are trying our best as a program, as an organization to be able to give them a second hope, to give them some future to their lives, because most cases is young people have been vulnerable, they have been left alone, they have low self-esteem, they have depression.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:He took me to meet 14-year-old Christopher. Two years ago, he dreamed of being a professional soccer player after completing school.What was your favorite subject?

Christopher, Uganda (through translator):Math and science.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Now he works from 4:00 in the morning until the national curfew at 7:00 p.m. at a food stand in Kampala’s Banda slum. His mother, Harriet Namoulondo, sells meat kebabs nearby.It is not enough, she says.Are you able to buy enough food for the family today?

Harriet Namoulondo, Uganda (through translator):We do not eat after lunch. That’s the end. We stopped eating dinner long ago.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:For its part, the government hopes to open schools by the new year, by when, it hopes, teachers and staff will be vaccinated.Health Minister Dr. Jane Ruth Aceng.Dr. Jane Ruth Aceng, Ugandan Minister of Health: We are losing a generation of people who would later on become economically productive and steer this country ahead.We are doing our best to ensure that we open schools as quickly as possible, but also open schools not to close them again.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Opening schools is only step one in what many activists say is a long road to repairing a public education system that is desperately short of the resources children and their teachers need.Although tuition is free, various fees and expenses for uniforms put school out of reach for many low-income Ugandans. Evelyn’s mom says she will do her best to send her and her six siblings back when schools reopen.

Sylvia Naggujja (through translator):I dream for my children to be OK, to be able to support themselves in the future, and also to be able to support me. I want my children to have a good life.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:“For now, I’m grateful for one thing,” she said. “None of my children has gotten ill or seriously injured.”For the “PBS NewsHour,” I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro just outside Kampala, Uganda.

Amna Nawaz:And Fred’s reporting is in partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

A growing crisis

2020 was the first year in two decades that saw an increase in child labor around the world. And with the pandemic devastating economies, the United Nations says the problem is getting much worse. It issued a report that found 160 million children, some as young as 5, working in child labor, many doing tasks that directly threaten their health and safety.

Evelyn, the child on the ladder, is 11 years old.

She works every day balancing on a makeshift ladder to crack open the rock face. Her family will then pound the larger rocks into gravel with crude hammers.

“Life is not OK. When I break these stones, sometimes, they cut my fingers. Sometimes, the small pebbles fall into my eyes. Life is not good… I miss school. I miss work at school. I work every day.”