A New Way to Deliver Medical Oxygen

Judy Woodruff:The pandemic is bringing new attention to a critical health care challenge plaguing many countries, a shortage or unreliable supply of medical oxygen. It’s also prompting many medical providers to look at ways to fix the problem.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports on one example in Uganda. It’s part of our series Breakthroughs.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Do you ever run out of space here? It looks pretty buys.

Ahairwe Adeodata, Nurse:Yes, yes. There are very many.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Bed space is almost always in short supply in public hospitals like this one in Uganda’s second largest city, Mbarara.But a bigger, ever-present concern for veteran head nurse Adeodata Ahairwe is having a steady supply of oxygen to save this premature infant and so many others.The lives of hundreds of patients every day in this Mbarara hospital depend on an uninterrupted supply of oxygen. In turn, the hospital’s oxygen plant depends on an uninterrupted supply of electricity. And, in Uganda, as in so many other countries, that is hardly guaranteed.UNICEF says the scarcity or irregular supply of oxygen contributes to hundreds of thousands of child deaths every year. Along with drugs like antibiotics, oxygen therapy is critical in treating pneumonia, at 800,000 victims each year, the biggest killer of children under 5. Pneumonia is often found in severe malaria cases, like that of 9-year-old Fridah, who was brought here by her dad, Posanio Bazamanza.

Posanio Bazamanza, Father (through translator):She was breathing really badly when we came. They put her on oxygen, and now I’m seeing her breathing improving and getting better.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Fridah is also one of the first few patients who’ve been put on a failsafe oxygen delivery system that’s being piloted in this hospital called OxyLink.

Sheillah Bagayana, Uganda Manager, FREO2 Foundation:So, basically, this is a very simple system that ensures that we have an uninterrupted supply of oxygen.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Sheillah Bagayana is a biomedical engineer and the Ugandan head of FREO2, an Australian nonprofit that invented this system.

Sheillah Bagayana:So, we have our concentrator, which makes oxygen from air. So…

Fred de Sam Lazaro:This is the oxygen concentrator.

Sheillah Bagayana:This is the concentrator.

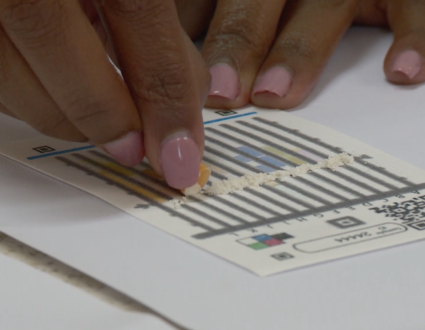

Fred de Sam Lazaro:That oxygen is pumped into the lower of two 50-gallon bladders, or flexible bags. On a shelf about six feet above it, the other bag is filled with water.

Sheillah Bagayana:When there is a power cut, oxygen then comes from the bag to the patient.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:In a power failure, she says, a sensor triggers the system to send water flowing by gravity from the upper bag to the lower.

Sheillah Bagayana:The weight of the water will flow down and push this oxygen to that patient.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Because the water is heavier than the oxygen. So it’s going to come down into this bag…

Sheillah Bagayana:And push it.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:… and push the oxygen.

Sheillah Bagayana:To the patient. Exactly.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Through the tubes to the patient.

Sheillah Bagayana:Exactly.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:And in the event of a long power outage, more than two hours perhaps, that would deplete the stored oxygen, she says a backup cylinder is on stand by.

Sheillah Bagayana:Normally we have short — short, but frequent power cuts.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Yes, but even a short power cut can mean the difference between life and death.

Sheillah Bagayana:Exactly.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:So far, it’s proven 100 percent reliable, she says, serving four pediatric patients at a time.FREO2, which is funded by several international charities, plans to scale up here and in 22 other rural East African hospitals. The focus will remain on pediatrics, but Bagayana says that benefits all patients.

Sheillah Bagayana:Usually, pediatric wards, neonatal wards, are some of the highest consumers of oxygen in our facility.So we find that, once we are able to provide reliable systems for, like, pediatrics, for neonatal, that then frees up more oxygen for the adults, for COVID and other cases.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Nurse Ahairwe, who has worked here for more than two decades, is encouraged by all the attention now being paid to the oxygen supply, attention that’s heightened by the pandemic.The improving supply is helping save many more lives than was possible just a few years ago, she says.How many patients would you lose?

Ahairwe Adeodata:Twenty percent of children because of oxygen. But these days, we’re doing 5 percent, 6 percent. They don’t die today because of oxygen. They die because of underlying conditions. But for oxygen, at least these days we are fine.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Allowing her, like so many more patients, to breathe more easily.For the “PBS NewsHour,” I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro in Mbarara, Uganda.

Judy Woodruff:Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

Oxygen delivery, even through power outages

This report covers one small but promising idea to tackle a critical health care challenge that has plagued many low resource countries: a shortage of medical oxygen, a problem that’s been particularly acute during COVID-19 surges.

“We find that, once we are able to provide reliable systems for pediatrics, for neonatal, that then frees up more oxygen for the adults, for COVID and other cases.”