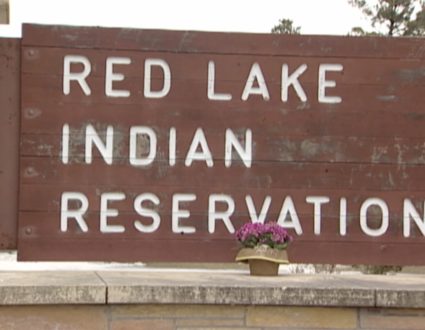

Judy Woodruff:Many schools across the country are also grappling with ways to close the achievement gap between white students and students of color.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro has a report on those efforts in Minnesota, a state with some of the greatest disparities.It’s part of our ongoing Race Matters coverage and Fred’s series Agents For Change.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:It’s a busy Monday in Thetis White’s fifth grade class at Monroe Elementary, math, English and even some history, all before lunch. White’s class in the Minneapolis suburb of Brooklyn Park is an outlier in this state, highly diverse and taught by a Black male.

Thetis White, Teacher:I grew up in Minnesota. I had I had some very impactful teachers, black, white. When I say that though, I didn’t have my first Black teacher until I was in seventh grade. All through my education, I had three teachers of color.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Even today, fewer than 1 percent of teachers in Minnesota are Black men.White’s own teaching career started less than three years ago, after working for UPS and spending more than a decade as a youth football coach. He eventually connected with Black Men Teach, a nonprofit that works to recruit, prepare, place and retain Black males in schools.

Thetis White:I really want them to understand that, especially for some of my African American students that are in my classroom, that you can be whoever you want to be, but you do have to have someone there that maybe looks like you letting you know that it is attainable.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Experts say the low number of teachers of color contributes to wide educational disparities in Minnesota. The state has historically ranked near the top in test scores and graduation rates. But those numbers mask wide differences between white and, in particular, Black students.This year, about 52 percent of white students met state standards for math, compared to 18 percent of Black students. And, on reading, 60 percent of white students were proficient, double the percentage of Black students.Nehemiah Johnson is a fifth grader in Thetis White’s class. He used to go to school in the Minneapolis Public School District. But his parents wanted something different.

Danielle Thompson, Mother of Nehemiah Johnson: All his teachers were older white women. And I felt every day with him that I would have to encourage him to ask for help. You know, don’t be intimidated. Don’t be nervous. Don’t be scared.It was more like he was uncomfortable.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:But, with White, Nehemiah has found confidence.

Nehemiah Johnson, Student:He helps me on my work in math and reading

Abdul Johnson, Father of Nehemiah Johnson: It’s good to see that someone cares. You know, a Black male teacher is showing that, expressing he cares about them. It probably would have helped, being that age, having a Mr. White. It definitely would have helped me.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:University of Minnesota Professor Justin Grinage studies racism and inequality in education.Growing up here, he says he didn’t have a single teacher of color until college, and understands from his own teaching experience why they’re so difficult to recruit and retain.

Justin Grinage, University of Minnesota: I would go up to a teacher and introduce myself. And about three or four times, they assumed I was security staff.It impacted my mental health, because I started to like, say, OK, how are people perceiving me? Should I even be a teacher? And I kind of got this complex, like, oh, I’m not good enough. And so that’s a subtle example, but, like, those things can accumulate.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Among the systemic challenges, Grinage says public education dollars are not distributed equitably between the state’s poorer and wealthier school districts.

Justin Grinage:There’s been wide societal inequalities that have existed for decades. And schools and classrooms don’t exist in a vacuum. Students of color, in particular, are put at a disadvantage because schools don’t necessarily function to close those gaps in any meaningful ways.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:In recent years, lawmakers, educators and researchers have searched for ways to close the gap. One effort is being led by two prominent figures in Minnesota, Alan Page, a former Minnesota Viking, NFL Hall of Famer and retired state Supreme Court justice, and Minneapolis Federal Reserve President Neel Kashkari.They have proposed an amendment to the state’s Constitution. The current language requires a general and uniform system of public schools funded by the legislature. The amendment says all children have a fundamental right to a quality public education and that fulfilling that right is a — quote — “paramount duty of the state.”

Alan Page, Former Minnesota Supreme Court Justice:It puts children first. Our current Constitution focuses on the education system and funding of that system. It doesn’t say one word about children.But we think it’s important that every child, no matter what their economic circumstance, no matter what the color of their skin, no matter their ability or disability, can learn. And our proposed amendment shifts the focus to individual children.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Under the amendment, the state would set standards for a quality education. Parents who feel they aren’t being met can seek remedies in the courts.But critics say that would only delay reforms. Denise Specht is the president of Education Minnesota, the state’s largest teachers union.

Denise Specht, President, Education Minnesota:It would require groups getting together to define things like quality. I do get a little worried when we are looking at a solution that is dependent highly on lawsuits. We see the urgent needs of students right in front of our faces right now.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Specht says the state could take more specific and immediate action.

Denise Specht, President, Education Minnesota:I actually wouldn’t mind if we were talking about a constitutional amendment that would specifically call for lower class sizes in our schools or universal health care for every student, universal pre-K for every student.Those are the things that we know are affecting the gaps right now. And I think we have to get down and figure those out.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Many critics say fixing the state’s education system doesn’t require a constitutional amendment.The argument being, the solutions ought to be legislated, not litigated.

Alan Page:There were probably those people that said that about Brown vs. The Board of Education. There are probably people who say that about a woman’s right to vote. There are probably people who said that about freed slaves’ right to vote.If we weren’t in the position we were in, and the current constitutional language was working, we wouldn’t be here having this conversation.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:The amendment has some bipartisan support, but it’s yet to pass the state legislature, which is required before it can be placed on the ballot.Amid the debate over reforms and how to enact them, there’s little disagreement on the importance of teachers like Thetis White.

Thetis White:This makes me emotional even thinking about it. I just really hope that somebody is going to see this and be turned into wanting to become a teacher, because we do need African-American teachers. They just have to want to step up.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Closing the education gap in this state may depend on it.For the “PBS NewsHour,” I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro in Brooklyn Park, Minnesota.

Judy Woodruff:Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

Trying to close the gaps in Minnesota

The state has historically ranked near the top in test scores and graduation rates. But those numbers mask wide differences between white and, in particular, Black students.

Experts say the low number of teachers of color contributes to wide educational disparities in Minnesota.

“There’s been wide societal inequalities that have existed for decades. And schools and classrooms don’t exist in a vacuum. Students of color, in particular, are put at a disadvantage because schools don’t necessarily function to close those gaps in any meaningful ways.”