Judy Woodruff:For decades, Black farmers have been excluded from federal farm programs, a systematic pattern of discrimination that the U.S. Department of Agriculture acknowledged decades ago.And yet proposals to compensate farmers for past wrongs have languished in controversy and red tape. The most recent include the Biden administration’s efforts to earmark such funds in its American Rescue Plan and now Build Back Better.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro begins his report in Northwest Kansas, as part of our ongoing series Race Matters.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Walking down this dirt road brings Bernard Bates back to the highest and lowest points of his 84 years.This land behind you goes back generations in your family?

Bernard Bates, Former Farmer:Yes, mm-hmm. Goes back to slavery.Karla Bates Adams, Daughter of Bernard Bates: Dad was a good farmer. He was one of the best ones in Graham County.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Dating way back to the ’40s, Karla Bates Adams says her father was a prolific producer here in Nicodemus, Kansas, a rare enclave of Black farmers whose ancestors settled here after they were freed from slavery.So, there was more land, that you owned different chunks of land?

Bernard Bates:North of the cemetery, there’s another 80 acres.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:In the early 1980s, amid the historic agricultural recession and crop disasters that hit the Midwest, many farmers fell behind on their loan payments, including Bernard Bates.

Bernard Bates:Bugs, hail, wind and rain, freeze, and everything for three, four years in a row.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:When he approached the U.S. Department of Agriculture for relief, Karla Bates Adams says, not for the first time, he was treated differently.

Karla Bates Adams:We know that the white farmers were getting the assistance, and the Black farmers were not.

Bernard Bates:They were getting all kinds of loans.

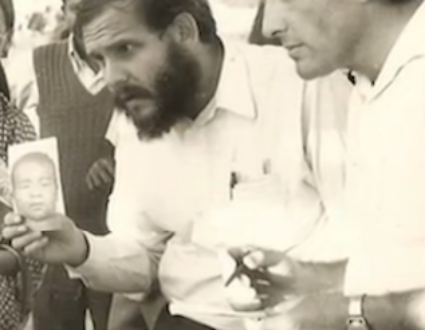

Fred de Sam Lazaro:The Bates then witnessed and even photographed the dismantling of their livelihood in foreclosure.That must have been very painful to witness.

Bernard Bates:Tell me about it.

Karla Bates Adams:They truly took our livelihood and then left my parents to have to go on food stamps.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Their land was subsequently sold off to white farmers.The Bates’ farmstead is among millions of acres of land that Black farmers have lost over the decades. In the 1920s, 14 percent of all farmers in the United States were African American. That number is down to less than 1.5 percent today.

JohnElla Holmes, Director, Kansas Black Farmers Association:There are men like Bernard that would still be farming, because that’s what he loves and that’s what he wanted to do.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Nicodemus resident JohnElla Holmes is a retired professor and director of the Kansas Black Farmers Association.For decades, she says, they have been excluded from federal agriculture programs, like price subsidies, disaster relief, and especially loans, the financial backbone of American agriculture.

JohnElla Holmes:Those loans are just — they’re just pivotal.Equipment is so expensive anymore that one single farmer, especially the small farmers, they can’t afford that equipment.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:In 1999 and again in 2010, Black farmers were offered limited compensation after a class-action suit. But the settlement was marred by allegations of fraudulent claims on one hand and the exclusion of possibly thousands of legitimate claimants on the other.Bernard Bates was a plaintiff.

Bernard Bates:I myself haven’t got one dime, not a dime.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:The Biden administration has included several billion dollars in loan forgiveness and other relief for distressed and disadvantaged farmers in its Build Back Better plan.

Tom Vilsack, U.S. Agriculture Secretary:We know for a fact that socially disadvantaged producers were discriminated against by the United States Department of Agriculture. We know this.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Earlier this year, Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack unveiled a similar $4 billion relief plan specifically for minority farmers in the American Rescue Plan.That triggered several lawsuits on behalf of white farmers, claiming reverse discrimination, and it succeeded in suspending the program, pending the outcome of the litigation.

Jon Stevens, Farmer:If a Black farmer lived across the road, and this bill went through, I see him get his mortgage paid off, it ticks me off because that was money stolen from me given to him.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Jon Stevens is a fifth-generation farmer in Pine County, Minnesota, and is a well-known advocate of the environmentally friendlier regenerative farming.Do you think that discrimination exists today against Black farmers?

Jon Stevens:As a federal system, I would say no. Now, when you go to your local office, sure. And that would go anyway, whether it’s white to Black, Black to white. Yes, there’s racist people all over this country.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:What are these plaintiffs not understanding?

JohnElla Holmes:Oh, I think they understand. I think they just don’t want to acknowledge the history.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Professor Holmes says that history of discrimination has taken an enormous toll on Black farm families that is still felt today.

JohnElla Holmes:We weren’t able to pass on wealth. We weren’t able to pass on a farm. And so to look at it and say, now, your field is level? No. Bernard Bates’ family were — they were denied the opportunity to continue to farm. That didn’t level the field.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Jon Stevens says white farmers are as likely today to face rejection at the USDA or at a private lender. He says the key is to persevere.

Jon Stevens:I don’t want to hear your victim story. So what if — what if I discriminated against you on something? Is that going to stop you?

Fred de Sam Lazaro:If you’re the government, possibly, or you’re the banker.

Jon Stevens:Go to another bank. Postpone it a couple years. If you want to be a farmer, if you want to be anything, just pick your bootstraps up and forget the rest of the world and do what you need to do.

Angela Dawson, Farmer:Well, I made my own straps and my own boots.(LAUGHTER)

Angela Dawson:And I’m pulling them up.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Angela Dawson farms just a few miles north of Stevens. Four years ago, she moved here in a career switch back to a family tradition that ended when her grandfather lost his farm.

Angela Dawson:You have to have at least 1,000, maybe 2,000, 10,000 acres in order to really be a sustainable farmer. And that’s something that I definitely didn’t have access to.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:So she tried to join the booming business of organic farming, whose humanely raised meat commands higher prices and therefore is feasible on a small farm.But when Dawson, who has a degree in business administration, presented her business plan with her loan application, she says the USDA agent was not convinced.

Angela Dawson:I was really enthusiastic about the pigs. And she said, “What are you doing here? “

Fred de Sam Lazaro:What do you think they were really asking you?

Angela Dawson:I felt like they were asking me, what makes me think I could do this?

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Despite an appeal, her application was rejected in a process that took 18 months, she says. Agriculture Department officials declined to comment specifically on this case.Dawson found a new passion as lucrative as it is controversial.

Angela Dawson:This one is a good one.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Hemp. The plant is now legal to grow in all states, its extracts sold for medicinal use.

Angela Dawson:My decision to go into hemp was driven by economics. For CBD hemp, the average farmer makes about $50,000 per acre.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Dawson’s farm is now the home base of a 33-member cooperative of minority-owned farms across the U.S.

Angela Dawson:This is the brain. This is the brain of the operation.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:The co-op guides members growing hemp on how to monitor the crop so it meets licensing standards.

Angela Dawson:We use regenerative practices, but we also use technology, and we don’t want people to get into farming to be poor.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Business has been great, she says, but that raised a red flag at one local bank, which closed her accounts.

Angela Dawson:The bank said that they thought I could be trafficking.So, the criminal image that’s associated with hemp and Black people is really difficult for me to overcome. So, it’s ever after, but we’re still working on the happily part.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Is it something that you would like to get back?

Bernard Bates:Oh, yes.

Karla Bates Adams:Yes.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Also waiting for happily ever after, the Bates family, hoping, by legal action or reparation, to buy back the land and legacy that they say was unjustly confiscated.

Karla Bates Adams:Bye.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:For the “PBS NewsHour,” I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro in Nicodemus, Kansas.

Judy Woodruff:Fred’s reporting is in partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

Systems of discrimination

For decades, Black farmers have been excluded from federal farm programs, a systematic pattern of discrimination that the U.S. Department of Agriculture acknowledged decades ago. And yet proposals to compensate farmers for past wrongs have languished in controversy and red tape. The most recent include the Biden administration’s efforts to earmark such funds in its American Rescue Plan and now Build Back Better.

Nicodemus resident JohnElla Holmes is a retired professor and director of the Kansas Black Farmers Association.

For decades, she says, they have been excluded from federal agriculture programs, like price subsidies, disaster relief, and especially loans, the financial backbone of American agriculture.

“We weren’t able to pass on wealth. We weren’t able to pass on a farm. And so to look at it and say, now, your field is level? No.”