Judy Woodruff:Three high-profile police killings of Black men in the past two years have led to ongoing conversations about racial justice in Minnesota. There has also been noticeable solidarity between the state’s African American and African immigrant populations.Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Qorsho Hassan’s second grade classroom at Echo Park Elementary is a diverse tapestry, students whose families are Native American, Nigerian, Mexican, Pakistani. The school, located in the Twin Cities suburb of Burnsville, is less than 40 percent white.

Qorsho Hassan, Teacher Teacher:Jackson, how would you describe the word culture?

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Today’s lesson is about honoring that diversity.

Qorsho Hassan, Teacher:Am I American too?

Class:Yes.

Qorsho Hassan, Teacher:Yes, I’m American too.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:It’s the kind of exercise that was rare for much of Hassan’s own upbringing, as the daughter of Somali immigrants, going to school in suburban Columbus, Ohio.

Qorsho Hassan, Teacher:The students didn’t look like me. My teachers didn’t look like me. I was hyper-visible. And so what I wanted from my teachers were for them to be affirming and caring and loving. And I hardly found that in my school experience.If you hear something that is racist or that doesn’t make sense, you can interrupt it. You can say, hey, stop, that’s not OK.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Hassan learned to embrace her dual identity as both Somali and Black, something she tries to instill in her students with similar backgrounds. Historically, she notes, there’s been tension between African immigrants and African Americans.

Qorsho Hassan, Teacher:We have really created this network, per se, of knowing who we are, respecting our differences, but also really understanding that we are powerful together.

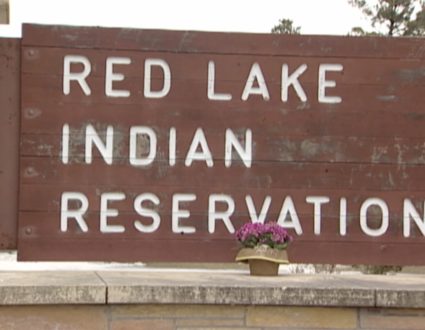

Fred de Sam Lazaro: Minnesota remains predominantly white, but its non-white population has grown over the past three decades. It’s about 24 percent today.Blacks have been a large part of that growth, including substantial immigration and refugee resettlement from across the African continent. And they have become far more engaged in politics and civic activism.In 2020, Esther Agbaje became the first Nigerian American elected to the Minnesota House of Representatives. A Harvard law school graduate, her work in the legislature has largely centered on issues of racial and social justice, particularly in housing.

State Rep. Ester Agbaje (D-MN):This is a state that, as you has worked on that ethos of what works best for a white middle-class people, rather than thinking about, what about everyone else we’re leaving behind, if that’s the only subset we’re thinking about?

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Agbaje’s parents moved to Minnesota from Nigeria, and experienced America not Only as foreigners, but also as people of color.

State Rep. Ester Agbaje:I grew up with the sense of knowing that there’s — yes, there’s different races across America, and yes, as a Black person, you tend to have to prove yourself a little bit more, and then, even as a foreigner, you have to work even harder to be able to be in these spaces.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Agbaje says her parents, like many other African immigrants, heard negative stereotypes about Black Americans. Journalist and Ph.D. Student Ibrahim Hirsi, a Somali immigrant himself, says those depictions were reinforced by a key American export, Hollywood movies.

Ibrahim Hirsi, Journalist and Doctoral Candidate: Sometimes, it’s, they don’t want to work, they’re lazy people. Sometimes, a majority of them are criminals or drug dealers. They live in neighborhoods that are very dangerous, and you should not be going around them.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:But the negative stereotyping went both ways.

James Burroughs II, Children’s Minnesota:I grew up watching Tarzan. And Tarzan showed me a white guy going through the jungle of Africa with Africans who didn’t look like they were very sophisticated.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:James Burroughs has worked on diversity and equity issues in Minnesota for decades. He’s now with the Children’s Minnesota health system.

Man:Witnesses say it was an all-out melee.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:In 2013, he was working for Minneapolis Public Schools when a brawl erupted at a local high school.

James Burroughs II:Some students had escalated a food fight into a physical altercation. There were a large number of African students, mostly Somali students, and a large number of African American students who seemed to be on opposite sides of the fight or altercation. And, at that time, we realized that we probably need to do something differently.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Burroughs had frequent and public meetings with Somali leaders and community members.

James Burroughs II:We talked about how we needed to work together and learn from each other about those myths and misinformation we got as kids, and basically learn about each other, our culture, our business acumen, our educational acumen, and move forward together. And our kids, our young people needed to see that as well.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:With time, Ibrahim Hirsi says, youth whose parents came from Africa began to forge their own identity.

Ibrahim Hirsi:Young people are saying, maybe we are Africans, right? We come from these different spaces. But, at the end of the day, there are no differences between us and African Americans.

State Rep. Ester Agbaje:When people of color, and especially Black people, face the police, it doesn’t matter what country you may have come from. They’re not checking for your last name. They’re not checking for your accent. They just see Black skin.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:So, when Minneapolis police killed George Floyd in May of 2020:

James Burroughs II:You saw folks with hijabs on in the march. You saw folks that were Liberian in the George Floyd March. You saw folks from Kenya in the George Floyd March. You saw lots of white people in the George Floyd March.So, it brought people together to say, I don’t want this happening to me or occurring in the future.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Teacher Qorsho Hassan went to the protests too. And Floyd’s killing had an impact on her mother, who was raised in Somalia and paid relatively little attention to issues of race.

Qorsho Hassan, Teacher:My mom watched the video, and was just in tears, primarily because of how George Floyd was calling out to his mother. That really tugged at our heartstrings.And it was just a moment of realizing that students, kids, children, are ready for these conversations and they need places and spaces to unpack them. And if we disregard their feelings and how they’re processing information, we are doing them a huge disservice.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Hassan won the Minnesota Teacher of the Year Award in 2020.

Qorsho Hassan, Teacher:Receiving that title validated who I was and how I connect with students, with all students, not just Somali students or Black or brown, and how I uplift and affirm their voices.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:And those voices are now being amplified at the state capitol by people like Ester Agbaje.

State Rep. Ester Agbaje:Saying that there’s only one piece of the pie that we’re allowed as Black people, and so then we have to fight among ourselves with that piece, and it’s like, no, there’s a whole — there’s a whole pie. We all can get a slice. We all deserve that slice.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:Agbaje has joined other African immigrants and African Americans in the People of Color and Indigenous Caucus, now more than 20 members’ strong.For the “PBS NewsHour,” I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro in the Twin Cities.

Judy Woodruff:And Fred’s reporting is in partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

Dual identities

Minnesota remains predominantly white, but its non-white population has grown over the past three decades. It’s about 24 percent today. Black people have been a large part of that growth, including substantial immigration and refugee resettlement from across the African continent. And they have become far more engaged in politics and civic activism.